What heritage cities offer us or what we experience in them depend on how we interpret the past. Heritage properties that are produced till the beginnings of 20th century are often prioritised as heritage and the entities of the following years may be ignored. Especially in the field of architecture, uses of traditional materials and techniques are easily acknowledged as heritage. Nevertheless, modern materials and techniques have been used since the end of 19th century and they have already become parts of our heritage.

Muğla, a small-scale heritage city of Turkey, is well-known about her vernacular settlements that are original in means of tangible and intangible entities. It is a well-conserved, silent living heritage city sustaining its original vernacular architecture together with the local inhabitants. Vernacular houses, public and commercial buildings of the 19th century and Early Republican Period are distinguishing, indisputable components of the heritage city of Muğla. However, we claim that there are more. In this study we analyse the buildings built between 1920s-1970s. This period is important for the transformation of the traditional settlement to a modern city and for the use of new manufactured building materials, but it is full of questions because there isn’t enough registered information about the buildings built in these years. So our research starts with oral history studies. We have interviews with the architects, engineers, and craftsmen of the years in question in order to understand the architectural practice of those years and make a list of buildings built in those years. Then we analyse them on site and propose a set of heritage values. Our study intends to enrich the heritage values of the city of Muğla by making room for the early modern years in our interpretation of heritage.

Heritage studies have expanded its scope from the old to the recent, from the grand to the civil, from the elitist to the mundane existence of everyday life. Any tangible or intangible assets around us can now be components of our heritage narratives. Harvey1 argues that “heritage has always been with us and has always been produced by people according to their contemporary concerns and experiences” and advocates heritage as a cultural process more than artefact or record. On the other hand, Smith2 asserts that there is a rather hegemonic discourse about heritage which acts to constitute the way we think, talk, and write about heritage, and heritage can unproblematically be identified as old, grand, monumental, and aesthetically pleasing sites, buildings, places, and artefacts.

Although scholars expand heritage definition by including everything about the human it is observed what Smith draws attention still affects the heritage practices. The official grand historical narratives still play an important role in heritage interpretations of cities. These official narratives, most of which are scientifically acceptable, tend to classify especially architectural heritage according to their recognizable characteristics generally in a chronological historic timeline. However, these classifications may not always be sufficient to describe all the heritage of cities, or they may be reductionist. Transition phases or ambiguous phases may be experienced out of or together with these classifications. In other words, what the grand narratives exclude or ignore may construct or contribute to the authenticity of a heritage city.

As it is widely accepted, the examples of vernacular architecture are the most important components of heritage cities. The conventional understanding of the term vernacular is equivalent to the word native meaning one belonging to the land in which he/she was born. However, the synonyms of the word are varied; anonymous, popular, indigenous, primitive, spontaneous, every day and shared are parts of these expressions3. ICOMOS Charter on vernacular heritage established in 1999 states that: “Vernacular building is the traditional and natural way by which communities house themselves.”4. Just like in heritage studies, the scope and definition of vernacular architecture have also expanded. Not only the traditional buildings but buildings and environments of people to be built in a particular place, at a particular time are accepted as components of vernacular architecture. It is conceptualized as the local dialect in built form. It carries local character that is identifiable with that particular community, particular area and it is a continuing process, including necessary changes and continuous adaptation as a response to social and environmental constraints. Considering the contemporary debates in both heritage interpretation and vernacular architecture studies, we are in the aim of analysing the ignored examples of vernacular architecture of a heritage city in Turkey which we believe will picture the life of the people of a certain period.

In Turkey architectural heritage, either as buildings or environments, is mainly categorized according to chronological timeline and described as archaeological (belonging to ancient period), historical (having values of grand narratives), monumental (having high architectural values of a period) or traditional (products of local materials and traditions). The term ‘vernacular’ is often used equivalent to the word ‘traditional’ defined as cultural relics, habits, knowledge, customs, and behaviours, which have the power of sanction and are respected and transmitted from generation to generation due to their old age in a community. In Turkey, it is often tended to limit the scope of the term vernacular mostly with traditional buildings which are the products of local materials – generally natural materials and local traditions handed from generation to generation. The buildings that go beyond these descriptions and classifications (especially those made of manufactured materials and not be examples of high architecture) are generally ignored or not noticeable.

Considering the contemporary debates in the field of heritage and vernacular architecture, we have an attempt to assert the buildings built in interlude of traditional to modern in a small-scale heritage city in Turkey, Muğla, as heritage buildings. Muğla is a well-preserved place of living heritage, which is well-known by its traditional vernacular heritage and authentic buildings/environments of the young Republic of Turkey, which was founded in the first quarter of the 20th century. Almost all the studies about the heritage of the city bring out basically its traditional vernacular architecture, and early republican monumental architecture. However, the environment of the city has been in a constant change and transformation with the introduction of new way of life, trades, manufactured materials etc. Today the city displays the examples of traditional vernacular architecture together with the high-rise concrete apartment blocks of modern times. Considering the current two categories of the city’s heritage that is suggested in the relevant studies and evaluating the present picture of the city, some questions arise: Has the construction of traditional buildings been given up suddenly and apartments started to be built? What happened to the traditional way of construction with the introduction of manufactured building materials? While the local people of Muğla were transforming with the republican revolutions in the first half of the 20th century, the craftsmen of the city had met with new manufactured building materials. How has the craftsman’s know-how of building changed?

Bozdoğan5 asserts that the architectural culture and production of the Early Republican Period in Turkey bears witness to the ambiguity, complexity and contradictions when imported modern ideas and local realities come across. With the revolutions of the Republic, social life has undergone significant changes in the way of Westernization. For Bozdoğan6 in order to be truly modern, Turkey should not lag behind the requirements of the time and the transformation should have started at residential home. So residential architecture had been the main representative of the understanding of modernity in this period. Tanyeli7 on the other hand, argues that residential architecture develops in its own way, apart from all kinds of grand narratives. Each region contains unique interpretations of 'modern' and modern materials in architecture in its locality and reality. In other words, it may not be possible to see the typical examples of modern architecture (cubic shaped architecture without ornaments) in residential architecture in every region. These opinions point out that there may be original, authentic, and remarkable examples in vernacular architecture of every region in the years after the proclamation of the Republic in Turkey. Original interpretation of the building masters or architects about modernity and tradition would probably house the ways of the authenticity of this period. The aim of this study is to document the vernacular examples of this period which are overlooked and unfortunately some of which are lost today in a typical authentic old city – Muğla, and thus contribute to heritage interpretation of the city. These buildings would both house the possible answers of above questions and picture what happened when modern and traditional encountered. With this study, we invite heritage researchers in Turkey to consider expanding the scope of vernacular heritage to include modern times.

The research consists of three phases: literature review, field observation and interviews. Actually, these phases were not sequential but carried out together because the writers needed to switch between the phases. The literature review covers the books, articles and theses written about the social, political, and cultural history of the city as well as its architectural heritage. The main intention is to correlate the information about the social and economic history of the city with the built environment. Interviews are held with both the elder construction practitioners like architects, building technicians, contractors, suppliers, and owners of the buildings in order to reach information about the way of building, designing, available construction materials and actors of building practice. We have had the list of the oldest architects who are still alive from the records of the Chamber of Architects in Muğla and held interviews with three architects between the ages of 65-85 about the period they practiced architecture and the previous periods. We have listed the names of other building practitioners working in the construction industry from them and interviewed with two construction masters and a topographical engineer worked in the municipality. Besides we have held questionaries with the owners of the buildings about the construction years of the buildings, building processes and materials used. In the light of the information obtained from interviews and literature review, the particular region of the city that is determined as the most developed area in the mentioned years is surveyed. Finally, a set of buildings that is thought to carry common architectural features of those years and some particular changes in traditional architecture of the city are put forward to be taken into consideration in the heritage interpretation of the city.

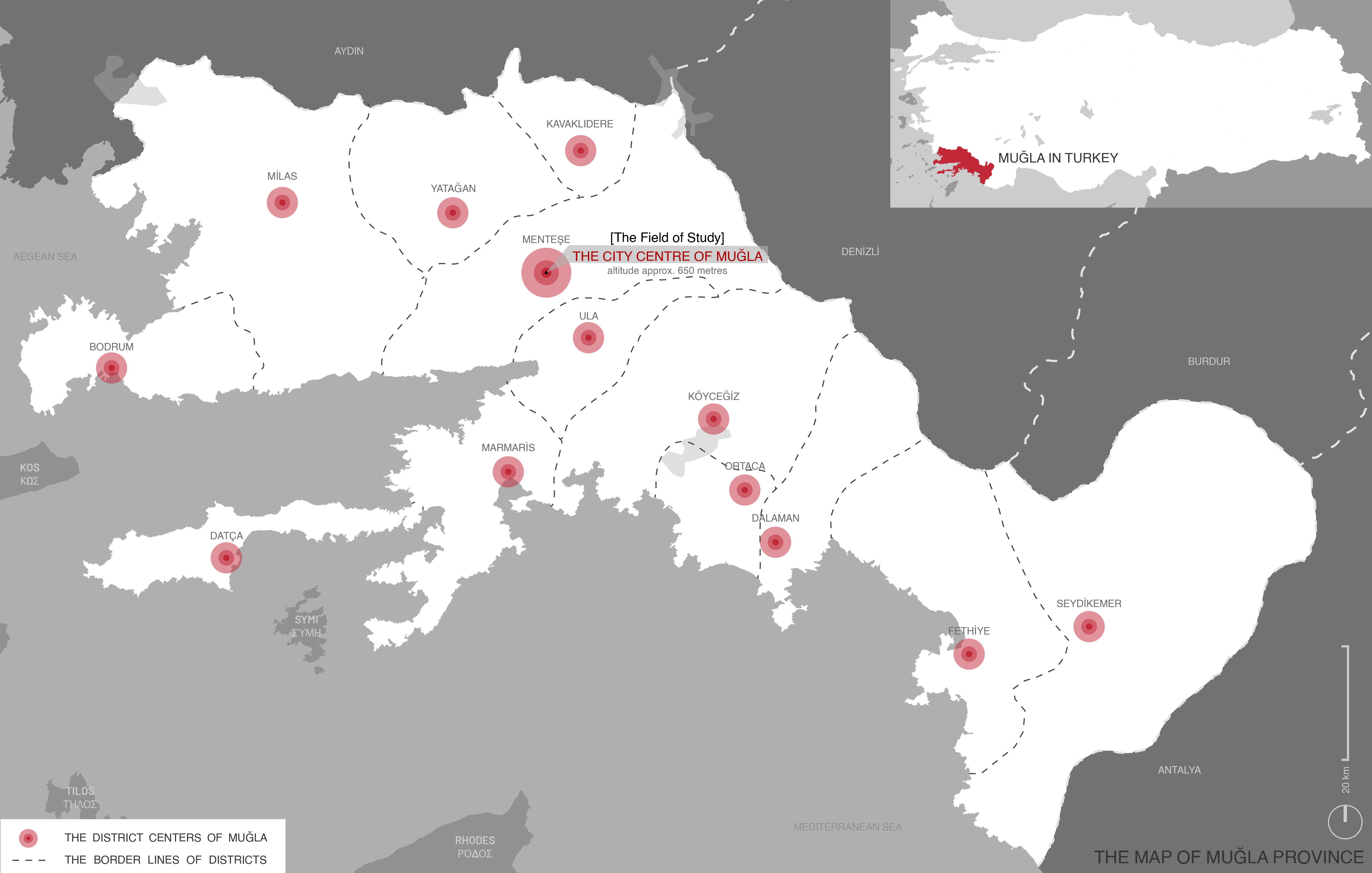

Muğla is a province located in south-eastern Turkey. It is very rich in terms of natural and cultural assets, as its western borders lines on the Aegean Sea and it has been inhabited continuously since history. The region of the province that is the subject of this study is the central settlement that gave its name to the province and is located relatively inside (fig. 1). It has the characteristics of a typical Anatolian traditional city, which is established on the slopes of a mountain and spreads through the slopes over time. The city’s history dates back to Bronze age and over time, it has been under the domination of, in chronological order, the Caria, the Egyptians, the Scythian, the Assyrians, the Doris, the Medes, the Persians, the Macedonians, the Romans and the Byzantines8. During these ages Muğla is supposed to be a small settlement on its own located on the mountain of Asartepe where it is still possible to see the remains of the antique and Byzantine period9. The traces of today’s living heritage city begin with the dominance of the Seljuk Turks in the 13th century and continue with the Ottoman domination in 15th century. In 1923 with the foundation of Turkish Republic the city has become one of the provinces of Turkey.

rendered by the authors

The 13th century is the period when the city is established as a border settlement of Seljuk State. It is settled by spreading to the southern slope of Asar Mountain around Karamuğla and Basmacı streams (fig. 2). During this period, it is thought that the settlement is concentrated around religious buildings, which is the typical Seljuk cities’ characteristics. The settlement might have consisted of neighbourhoods defined by masjids (small mosques) and contained institutions of the Islamic cultural world such as dervish lodges, zawiyas (Islamic monasteries) and madrasahs (Muslim theological schools) between the 13th and 15th centuries10. In this period, the southern border of the city is the Sekibaşı-Dibekli road, and the settlement is completely on the slope. With the Ottoman domination in the 15th century, the city grows a little further to the south, the Kurşunlu complex is built and the commercial centre, which is still active today, develops. In the 17th century, the Turkish travel writer Evliya Çelebi describes the settlement as a pretty one including 2170 houses, 70 mihrabs (mosques) and eleven neighbourhoods11. It is thought that the morphology of the city doesn’t change much until the 19th century, it preserves the appearance of a limited hillside settlement with the caravan road passing from the south (Sekibaşı-Dibekli road), and the commercial centre remains around Kurşunlu Mosque (fig. 2).

Until the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th century, the urban fabric is characterized by one or two-storeyed houses in courtyards, either with flat or tiled roofs. The houses are oriented to the south and to the courtyard, while the north-facing facades are closed and the courtyard-facing facades are open. This type of settlement also determines the street character, and the streets parallel to the slope are defined by high courtyard walls on one side and closed rear facades on the other. As elements of an Ottoman City, white washed stone buildings, high courtyard walls overflowing with plants, wooden doors and windows, and authentic chimneys are recognizable vernacular characteristics of Muğla in this period (fig. 3). Cansever13 describes the Ottoman city as a city that consists of houses on a calm and lively road scheme, whose location, shape, and personality change along the way: As you pass between houses with different colours, you see the flowers or fruit trees hanging from the walls and you encounter a new beauty at every moment. He adds that many people may see this irregular road network as chaos, but while the Ottoman city is constantly changing, you can see it as a beauty to be savoured, without being bothered by change. The traditional settlement of the city of Muğla can be described as a living example of this original depiction of Cansever.

photographs by the authors

In the 19th century economic, social, and political changes in the aim of Westernization affect the entire Ottoman Empire and as well city of Muğla. New social functions and buildings like governorate, municipal headship, hospitals, schools, public squares, and parks are added to the urban fabric. The small administrative square located in Konakaltı region is formed by these new structures with a large park infront (fig. 2). Parallel to the new lifestyle and values, influenced by the relations of the West with the Ottoman Empire new stone residences with extrovert and neo-classical features begin to appear, especially in Konakaltı and Saburhane neighbourhoods14. Therefore, it is possible to talk about a different urban fabric in the 19th century than in previous centuries. Outdoors, roads and squares have become more important. The buildings are located according to the predetermined outdoor spaces, not by following the traditional rules as in the previous traditional process. Geometric layout is intended. Social class differentiation is reflected in the settlement. Extraverted, two storey stone mansions with inner sofas are recognisable vernacular forms of 19th century15 (fig. 4).

photographs by the authors

With the establishment of the Republic in 1923, revolutions take place in economic, social, cultural, and political life with the aim of modernization. The effects of these revolutions reflect to physical environment of Muğla through 1930s. During this period, it is envisaged that Muğla would develop towards the south with smooth roads and geometric building blocks. Accordingly, Republican Square is designed and implemented with its current circular form, and important buildings of the Republic such as the Public House and the Government House are located around this square (fig. 2). New building types shaped by the new lifestyle and values of the Republic (primary school, club, cinema, hotel, bank, and restaurant) have started to appear in the city rapidly. The location of these structures is between the newly formed square and the 19th century administrative centre and the traditional commercial centre that was and is still alive (fig. 2). The recognisable buildings of the republican period are the government-built structures and the houses of the notables of the society (fig. 4).

The above chronological history narrative has constructed the interpretation of Muğla's architectural heritage until today. The vernacular architectural examples of traditional character and monumental architecture of the Early Republican Period have already been registered as heritage. However, the physical environment has continued to develop and change in the following years after the foundation of Republic. The buildings of the following years, especially civil architectures, have not been the subject of academic studies and they have not been discussed comprehensively whether they have heritage values. There is a gap in architectural history of the city between the years 1930s, first years of the Republic, and the beginnings of 1970s when it is possible to reach information about the built environment via the architects still alive today or municipality registers.

We name this period, between 1920s and 1970s, as ambiguous because all the determinants shaping the physical environment have been in constant change. People have met new lifestyles; builders have encountered new building materials and thus new experiences are produced in all segments of life. At the same time, it can be considered as an interlude until the 1970s, when traditional building materials and construction systems were completely abandoned, and way of modern architecture has taken place. We have the information that new modern building materials had started to be used in the 1930s via the government-built buildings.

However, we do not know the exact time of the abandonment of applications of traditional ways of building. The interviews we conducted in the field and the information we supplied from the registers of the municipality point out that after the years 1970s, the use of new building materials in modern style completely dominate the architectural practice. Therefore, the years between 1930s and 1970s characterize a period where traditional building practice was transformed and largely disappeared to be replaced by modern building knowledge. This period can be interpreted as the localization of modern architecture as well. In both cases, it is clear that the traditional and the modern come across, influence each other and a characteristic physical environment emerges (fig. 5).

Turkey enthusiastically embraced the revolutions of the New Republic in 1923 and the breakthroughs in social, economic, and cultural life rapidly reshaped the physical environment. Although many complex and diverse determinants are discussed in literature, there appears four primary factors influencing the formation of the physical environment after 1923; first is the new socio-cultural life introduced by the Republic, second is the new idea of city planning, third is the availability of new building materials and the last is the stakeholders in building practice. After the proclamation of the Republic, social life in Muğla, as in the rest of Turkey, was revitalized, people met with new socialization venues such as cinema clubs, women became more visible in the public sphere, education became widespread, large families were split into nuclear families16. Since the image of the small nuclear family consisting of a working husband and father, an educated wife and mother, and their healthy child or children was idealized, the physical space of the house was also represented with a western expression17.On the other hand, the Republic brought a new understanding of planning, a city plan was prepared for the first time in 1936 and according to this, it was envisaged that the physical environment would grow to the south within geometric building blocks divided by wide roads. This foresight was also developed in the later city plans18.

photographs by the authors

Introduction of modern building materials to the city via the newly developed highway connections with big cities, especially İzmir which was an important seaport of Turkey, was one of the main factors that brought out changes in buildings. Until the proclamation of the Republic, the highway connection of the city with the surrounding provinces was underdeveloped, unsuitable for the use of motor vehicles, which made it difficult to enter manufactured goods to the city. Only lime and tiles were produced in the city. Natural building materials like stone and wood were readily available. Accessibility to brick, cement and iron had increased since the 1950s, and these materials had emerged almost simultaneously in the building constructions of Muğla after the 1950s19. Lastly, new stakeholders had taken part in building practice like architects, engineers, construction technicians and contractors. However, it takes time for them to be active. Architects and engineers were almost lacking in the building practice until the 1970s. There are only three architects we know worked in Muğla and they left the city after a few years after their start. Before the Republican period, Greek craftsmen dominated the building practice, and after the population exchange in 1922 Turkish craftsmen who were the trainers of Greek masters replaced20. Building master Şekerin Mehmet Usta, carpenter master Hacı İbrahimoğlu Mustafa Usta, Yeni İsmailoğlu Mehmet Salih Usta are among the names that are remembered today. Between 1950s-1970s building technicians who were trained for technical drawings conducted the design and planning services and they did not have control over the entire building process. Still craftsmen might have managed the construction of the buildings. After 1970s we know architects and engineers gained the authority of design and control of building activities.

The city centre comprising the area between Kurşunlu Mosque, Konakaltı Square and Republican Square is approved to be alive between 1930 and 1970 both culturally and commercially. Likewise, it is figured out that the area between Konakaltı Square and Republican Square appears to be attractive zone of the city for new buildings. Due to these reasons the field study is conducted on these areas actually where are still alive (fig. 6). 44 buildings in sum are determined to be built in the period and they are analysed according to their common properties considering the above-mentioned determinants of physical environment (fig. 7). Analysing the sum of the buildings documented, it is difficult to derive stable architectural typologies, but it is possible to group some common properties which we have divided into two. The first group pictures common properties of the buildings which continue to carry some characteristics of traditional architecture but also have got considerable changes (fig. 9). The second group comprises buildings which carry more modern architecture features but still have got traces of traditional architecture (fig. 10). For better comprehension of these two groups, it is necessary to put forward the general characteristics of the traditional architecture of Muğla.

rendered by the authors

Distinctive Characteristics of Traditional Vernacular Architecture in Muğla: Native people or local builders build traditional buildings with the help of simple tools and materials available around. These buildings respond to the traditional requirements of pre-industrial communities and to the restraints of locality and climate. The houses are placed as parallel to the slope as possible and in such a way that they do not interrupt each other's view and light. Rural life based on agriculture is designed in a private way to meet the requirements of the religion of Islam, and the houses are introverted, closed to the street and open to the courtyard in front of them. High stone walls separate the courtyard from the street. So the traditional settlement is characterized by its narrow, sinuous streets defined by whitewashed walls, wooden courtyard doors, wooden windows above eye level and they are shadowed by long wooden eaves of the houses and vegetation hanging from the courtyards. The traditional vernacular house of Muğla has a plan setup with a sofa. Sofa is the common space between rooms which provides both circulation and gathering of the users21. The houses of families based on agriculture generally have an outer sofa and integrate with the courtyard in front of the house. However, the houses, which belong to families with non-agricultural occupations and started to be seen mostly after the middle of the 19th century, have a plan with an inner sofa. These houses are ostentatious because they are the homes of the notables of the society and wealthier families. They are more integrated with the street; the entrance to the building is directly to the inner hall, and the ground floor now has windows opening to the street (fig. 8).

Either in plan type of outer or inner sofa all the traditional houses respond to Mediterranean Climate, which is distinguished by its warm and rainy winters, and hot-dry summers. The settlement is founded on the hillside of Asartepe facing south, so all the houses face south, southeast, southwest in order to get more out of the sun. The buildings consist of cubical structures with whitewashed thick masonry walls enveloping the inner spaces from prevailing wind directions. Window openings are small and equipped with shutters. Roofs were first covered with earth but in time replaced with tiled roofs with the availability of tiles. Stone, wood, earth, and lime are the local building materials found in the immediate vicinity of Muğla. Stone is used in a mixed system with wood. The building is surrounded by thick stone walls in the direction of the prevailing wind, and the inner walls are infill walls between the wooden frames. Floors and roofs are wooden. Outer facades of stone walls are left white washed whereas the inner facades of all the walls are plastered with earth and lime. These two recognizable traditional types were the basic typologies that the craftsmen handled from generation to generation till the introduction of new building materials to the city.

Until the end of the second quarter of the 20th century we know that only nails are supplied from the other cities22; traditional building materials available from close vicinity are on use. By means of the economic opportunities provided by the Republic, it has become possible to use new modern building materials, like cement, reinforcing bar and brick. However, it must have taken time for these materials to become widespread. New building materials are observed first in government-built buildings and in some houses of notables23. The interviews point out that the use of concrete could be affordable around 1950s and correspondingly it has taken time for the masters to develop skills with these materials. We know that experts like architects, construction technicians and engineers appear in building practice in Muğla after 1920s, however they are very few and work for the government24. Therefore, in these years, building activities must have been dominated by local craftsmen, which means the building knowledge in the minds of the masters has been reshaped with new way of life and new materials.

It is analysed that the determinants from climate, topography and lifestyle maintain their continuities; plan layouts responding to urban way of life with inner sofa continue. The plan type of inner sofa is adopted to new way of life. In some examples it is observed that small bathrooms are included inside. Façade arrangements remain basically the same, but the proportions of the windows change from rectangle to square by means of the use of concrete window lintels. Rough plasters with cement and addition of small concrete balconies on facades are distinctive features added in this period. The basic difference is the replacement of stone with brick masonry. The masters wall the buildings with blend brick which is yet available in the city and it is observed that use of framed walls slowly disappears. The floor slabs continue to be often wooden whereas in some examples concrete slabs are observed, which denotes that the masters are experimenting with new materials. All of these changes can be observed totally in a single structure as well as separately. For example, a concrete balcony can be added to a traditional vernacular house or while all traditional features remain the same, cement-based plaster can be seen. This period picture that the traditional master is introduced to the new materials, and he is experimenting with them (fig. 9).

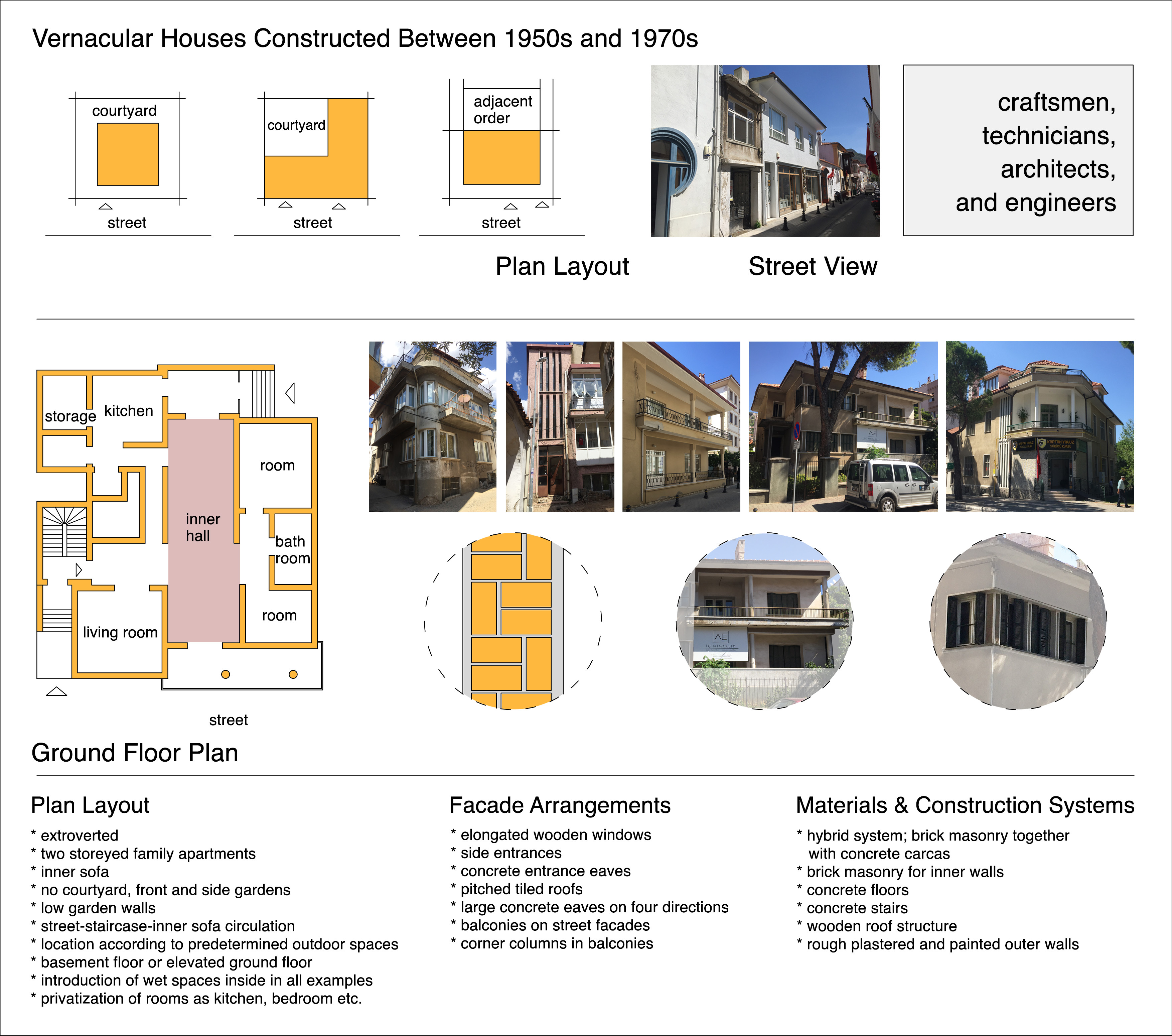

In the following years, between1950s-1970s, the modern way of life introduced by the Republic is approved and becomes widespread. The city grows in geometric layouts through south and out of the traditional settlements. It is much more possible for the local to reach new manufactured building materials. New actors like construction technicians who have ability to produce technical drawings emerge in building practice. Two or three storeyed apartment blocks whose flats are housed by the members of a family are the prominent examples of this period. Although an apartment block is a totally different type of housing it is observed that a common space similar to inner sofa which is the characteristics of traditional houses is still the focus of the plan. It turns to be either a larger living area integrated with outside via a wide, elongated balcony or a hall for circulation. The plan layout becomes more complex; rooms are customised according to special uses like bedroom, kitchen etc., and wet spaces are now located inside. Extended families living together in traditional houses are broken into elementary ones, women are more outside and working, private zones of the families become smaller, and the public spaces get crowded. So the houses are more extroverted and integrated with the street. (fig. 10).

A hybrid system in which the brick masonry construction system and reinforced concrete carcass is observed in these buildings. Still there seems a hesitation for the use of reinforced concrete system because thick brick walls remain as bearers together with reinforced columns while the foundation and floors become completely reinforced concrete. The eaves are now concrete and turn around the building on all four sides. The entrance of the building is generally placed on one side of the building that is perpendicular to the street, sheltered with an independent eave either cantilever or carried by a column and it opens to a hall big enough to fit the staircase and the staircase is now concrete. Elongated balconies facing the street that are characterised by circular corner columns, iron balustrades, rough plaster and square or horizontally placed windows are recognizable architectural features of these buildings. (fig. 10).

Since transportation and communication opportunities have developed and building experts like architects and engineers become decision makers of the physical environment, the international and national architectural movements influence the vernacular architecture of the city in this period. Linear and curved contours of the buildings, cubic and volumetric compositions reveal modern style in architecture. In other words, the buildings of this period picture the confrontation of modern architecture with traditional tenets.

The traditional vernacular buildings of Muğla have already been approved and interpreted as tangible heritage examples of the city to be conserved like in other cities of Turkey. As it is analysed comprehensively in this study, the buildings of the following years covering 1920s to 1970s also have got heritage values telling particular socio-cultural stories of the society. These values are interpreted as follows.

Documentary value: These buildings display local interpretations unique to Muğla in the transition from traditional to modern building production. It can be asserted that they are the documents of the westernization and modernization movements that are introduced with the Republic observed in the built environment in the peripheral Anatolian cities. On the other hand, they picture how the local master’s experiment with new modern building materials and how architects deal with in the light of traditional architecture.

Architectural/Identity value: These buildings respond to the social and economic requirements of the society in these particular years. They stand as representatives of the local people who first meet the opportunities of young Republic and step into modern times. Responding to changes in social life, the layouts of the building have become more complex than the traditional times, courtyards have lost, gardens around the buildings emerged, balconies are added to street silhouettes, window openings increase in number and size, and the houses are planned more extraverted. The effects of the national and international architectural trends of the period are also observed. The authentic traditional buildings on one side and on the other identical multi-storeyed apartment blocks of today, it is clear that these buildings carry particular architectural and social values of the local people of Muğla between the mentioned years.

Structural/Physical Value: These buildings can be easily adopted to today’s requirements since they are early examples of modern times. They comprise a considerable part in the building stock of the city and reuse of these houses will contribute to the sustainability of the physical environment. The load bearing system of these buildings is a hybrid system that combines masonry and reinforced concrete and because the brick walls are thick enough, they can respond to current rules for earthquakes.

Urban Value: These houses which have documentary and architectural value, are also valuable in terms of the historical urban fabric in which they are located. They are part of urban change. Together with the traditional and modern houses around them, they have the value of integrity. Their absence will create a gap in the history of the city.

The contemporary notion of heritage includes everything that is part of the society’s life and can be preserved for future generations. The growing interest in heritage in the last years is partly motivated by a sense of nostalgia and being lost, in contrast to the turbulent present. David Lowenthal25 describes it as follows: dissatisfaction with the present and malaise about the future induce many to look back with nostalgia, to equate what is beautiful and livable. This is apparent in tourism and heritage conservation practices that mainly the examples of picturesque traditional or monumental buildings attract the attention of people and heritage experts. Though the old, monumental, and aesthetically pleasing sites still shape the popular heritage interpretations, as Smith26 argues, Harvey27 asserts that heritage is produced by people according to their concerns and needs so anything could become heritage. Considering these debates in heritage studies a particular period in the history of Muğla that is ignored is analysed in this study. A group of buildings carrying the original characteristics of the period is suggested to be included in heritage interpretation of the city and to be preserved.

Muğla, a small-scale living heritage city of Turkey, is famous with its traditional vernacular buildings, and monumental buildings of early Republic founded in 1923. The years after Republic and before 1980 are important for the city because it is the period of change and transition from traditional to modern. The buildings listed in this study respond to requirements of the society that is seeking its way to modern so the architecture in this period is in trail–and–errors. Maybe they are not aesthetically pleasing the eyes or evoking nostalgia for people, but they are documenting a particular period whose absence will create a gap in the urban history.

notes

Harvey, D.C. 2001. Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 7(4): 319-338, DOI: 10.1080/13581650120105534, p.320.

Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge, p.11.

Lawrence, R.J. 1983. The Interpretation of Vernacular Architecture. Vernacular Architecture 14(1): 19-28. DOI: 10.1179/Vea.1983.14.1.19.

ICOMOS 12th General Assembly. 1999. Charter on the Built Vernacular Heritage, October 1999 in Mexico. Available at https://www.icomos.org/images/DOCUMENTS/Charters /vernacular_e.pdf [Last accessed 15 August 2022].

Bozdoğan, S. 2002. Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, p.6.

Ibid, pp.195-196.

Tanyeli, U. 2005. İstanbul 1900-2000 Konutu ve Modernleşmeyi Metropolden Okumak. İstanbul: Ofset Yapımevi Yayınları.

Günsan, O. 1973. Muğla İl Yıllığı. İzmir: Dizgi Baskı Ticaret Matbaacılık T.A.Ş.

Ekinci, O. 1985. Yaşayan Muğla. İstanbul: Bilimsel Eserler Kollektif Şirketi, p.22.

Akcura, N. 1993. Muğla’da Geleceğe Yönelik Çabalar Tarihi Çevre Koruması. In: İlhan Tekeli (ed.) Tarih İçinde Muğla. Ankara: Faculty of Architecture Press, Middle East Technical University. pp.240-333, p.246.

Eroğlu, Z. 1939. Muğla Tarihi. İzmir: Marifet Basımevi, p.139.

For comprehensive Muğla mapping: Koca, F. 2015. The Historical Transformation of Urban Space Within the Context of Property-Society Relations in Muğla, Turkey. METU JFA. 32(1): 203-228, DOI: 10.4305/METU.JFA.2015.1.11. P.211.

Cansever, T. 2013. Osmanlı Şehri. İstanbul: Timaş Yayınları, p.99.

Aktüre, S. 1993. 19. Yüzyılda Muğla. In: İlhan Tekeli (ed.) Tarih İçinde Muğla. Ankara: Faculty of Architecture Press, Middle East Technical University. pp.34-114, p.105.

Ibid, p.257.

Akça, B. 2002. Sosyal Siyasal ve Ekonomik Yönüyle Muğla (1923-1960). Ankara: Atatürk Araştırma Merkezi.

Bozdoğan, S. 2002. Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Osmay, S. 1993. 1950-1987 Döneminde Muğla Kenti. In: İlhan Tekeli (ed.) Tarih İçinde Muğla. Ankara: Faculty of Architecture Press, Middle East Technical University. pp.188-240, p.229.

Tekeli, İ. 1993. 1923-1950 Döneminde Muğla’da Olan Gelişmeler. In: İlhan Tekeli (ed.) Tarih İçinde Muğla. Ankara: Faculty of Architecture Press, Middle East Technical University. pp.114-188. P. 167.

Ibid, p. 167.

Eldem, S.H. 1968. Türk Evi Plan Tipleri. İstanbul: İTÜ Mimarlık Fakültesi, p.16.

ekeli, İ. 1993. 1923-1950 Döneminde Muğla’da Olan Gelişmeler. In: İlhan Tekeli (ed.) Tarih İçinde Muğla. Ankara: Faculty of Architecture Press, Middle East Technical University. pp.114-188. P.167.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Lowenthal, D. 1985. The Past is a Foreign Country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Smith, L. 2006. Uses of Heritage. London and New York: Routledge.

Harvey, D.C. 2001. Heritage Pasts and Heritage Presents: temporality, meaning and the scope of heritage studies. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 7(4): 319-338, DOI: 10.1080/13581650120105534

Daniela Bustamante

Federico Bucci

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Beatrice Moretti (Università di Genova) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Edited by: Elisa Boeri (Politecnico di Milano) and Francesca Giudetti (Politecnico di Milano)

![Figure 2. Map of the city of Muğla showing its development in history. [12]](https://adh.quivi.it/storage/app/uploads/public/63d/254/813/thumb_47_0_0_0_0_auto.jpg)