The demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing estate (1951) has become one of the most well-known and potent images in the history of modern architecture, demonstrating the central role of media in shaping architectural narratives, as much as the building’s destruction was evidence of any real historical juncture. The images published by Charles Jencks in The Language of Post-Modern Architecture to encapsulate the ‘death’ of modernism, are of the demolition of Building C-15 that took place on 21 April 19721. The spectacle was widely televised nationally, and photographs circulated within hours (fig. 1). What is less well known is that this implosion was, in fact, a trial demolition event, not a fait accompli—an attempt to revitalize the building complex by reducing the number of units and creating additional park area by removing three towers. The theatricality of the implosive blast was captured by CBS and Associated Press “creating a visual episode that would simplify the narratives of the housing project for generations2”. As Allen and Wendl have explained, the Pruitt-Igoe complex was not finally demolished until 1977, when the remaining 31 towers of the complex were demolished less dramatically by conventional wrecking ball between January 1976 and spring 1977 leaving a derelict site that remained undeveloped for decades3. Yet the images of Building C-15’s implosion have cast its demolition as a singular moment, and an architectural trope symbolic of a wider failure.

Building demolition continues to be a flashpoint in architecture, encapsulating temporal breaks, intractable debates, and even culture wars. This article considers the mediation of demolition, and how it has served as a conduit for debates about built environment quality. It discusses the Channel 4 television series Demolition in relation to a broader discussion of built environment governance, with a particular focus on shifting attitudes towards demolition and conservation.

The television series Demolition was broadcast on UK’s Channel 4 in December 20054 over four episodes, the series presented a selection of Britain’s so-called worst buildings, interrogating their design flaws, asking why they were still standing if they were so dysfunctional and unloved, and considering what could be done about it. The series transposed public voting with the commentary of expert presenters to create a frisson between popular and expert judgement in the evaluation of the built environment. An accompanying web-based platform facilitated public discussion and provided additional information on built environment governance and avenues for citizen participation. In this respect, Demolition can be understood as an early example of reality television involving multi-platform audience engagement. This incorporation of interactive content via a digital interface was an emerging practice at the time and functioned to expand the social dimension of television, at a time when new digital media forms were diffusing its dominance as a mass medium.

The series premise sought to sensationalize demolition and promised the visual spectacle of the destruction of the eyesores buildings that blight our built environment—an expedient and spectacular fix to an ostensibly intractable problem. However, as discussed here, it can also be argued that the series opened a broader conversation about the built environment that aimed to reveal the complexity of urban development and the levers that effect its quality. The series, and its critical reception, chart how changing standards of public taste complicate built environment governance, but also how changing expectations for keeping buildings adds a new and urgent layer to the contest between heritage conservation and creative destruction that is otherwise played out in the series.

Produced by Oxford Film and Television and presented by Kevin McCloud, Demolition was conceived as a counterpoint to the Restoration series (BBC, 2003-2006) presented by Griff Rhys Jones. Restoration invited audiences to vote for a heritage conservation project, from a group of contenders presented across each series, with the most popular project ultimately awarded a Heritage Lottery Grant and money generated from the public telephone-based voting process. Journalist and media personality Janet Street-Porter’s reaction to this series seeded the idea for Demolition. In her column for the Independent in May 2004, she outlined her frustration at the conservativism of the Restoration series. Street-Porter had studied architecture before becoming a journalist. She saw Restoration as symptomatic of a wider malaise born out of a “British obsession with saving crappy second-rate buildings from yesteryear5”. To shock the reader out of their cosy heritage-induced stupor, or more simply to highlight the naturalization of the heritage industry, Street-Porter suggested that instead their ought to be “a series called Demolition, in which I nominate 10 buildings that I think should be torn down, and you, the viewer, have to vote to save nine of them6”. Even though the heritage industry was Street-Porter’s explicit target, her main complaint was with the lack of opportunity for the construction of innovative contemporary architecture, a situation she herself sought to rectify through the commissioning of houses from Piers Gough (CZWG, 1988) and David Adjaye (2001)7.

At the same time, in April 2004, architect George Ferguson, newly elected president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA, 2003-5), raised the idea of creating an ‘X-list’ of ‘eyesore’ buildings, as a corollary to heritage listing. In his words, X-listing would be a new category for listing “buildings that deserve to be torn down8”. Yet, this was no simple modernist tabula rasa redux. Ferguson was not against heritage per se. In fact, his own practice included conservation and adaptive reuse projects. Rather, his X-list proposal would facilitate a form of curation of the built environment with placemaking in mind. An important element in Ferguson’s proposal was that “a Grade-X listing could release fiscal incentives to demolish ugly buildings9” and provide “grants to encourage the removal of buildings and structures that are universally judged to damage the environment10”. This was not only a mean to improve the quality of the built environment, but also a mechanism to intervene in property speculation, whereby development, and the demolition and dereliction that comes with it, could be more consciously and effectively managed and governed. Ferguson’s somewhat sensationalist proposition was of course meant to garner attention, not only in the architecture profession, but also from the broader public. Part of his election platform for the RIBA presidency proposed to exploit television as a medium to promote the value of good design and improve design literacy11.

The series brought the ideas of Street-Porter and Ferguson together: Street-Porter’s idea of public voting on building demolition and exploiting television to mediate public taste, and Ferguson’s idea that the demolition of buildings could benefit from better governance. Both Street-Porter and Ferguson appeared as presenters in Demolition alongside the main presenter Kevin McCloud.

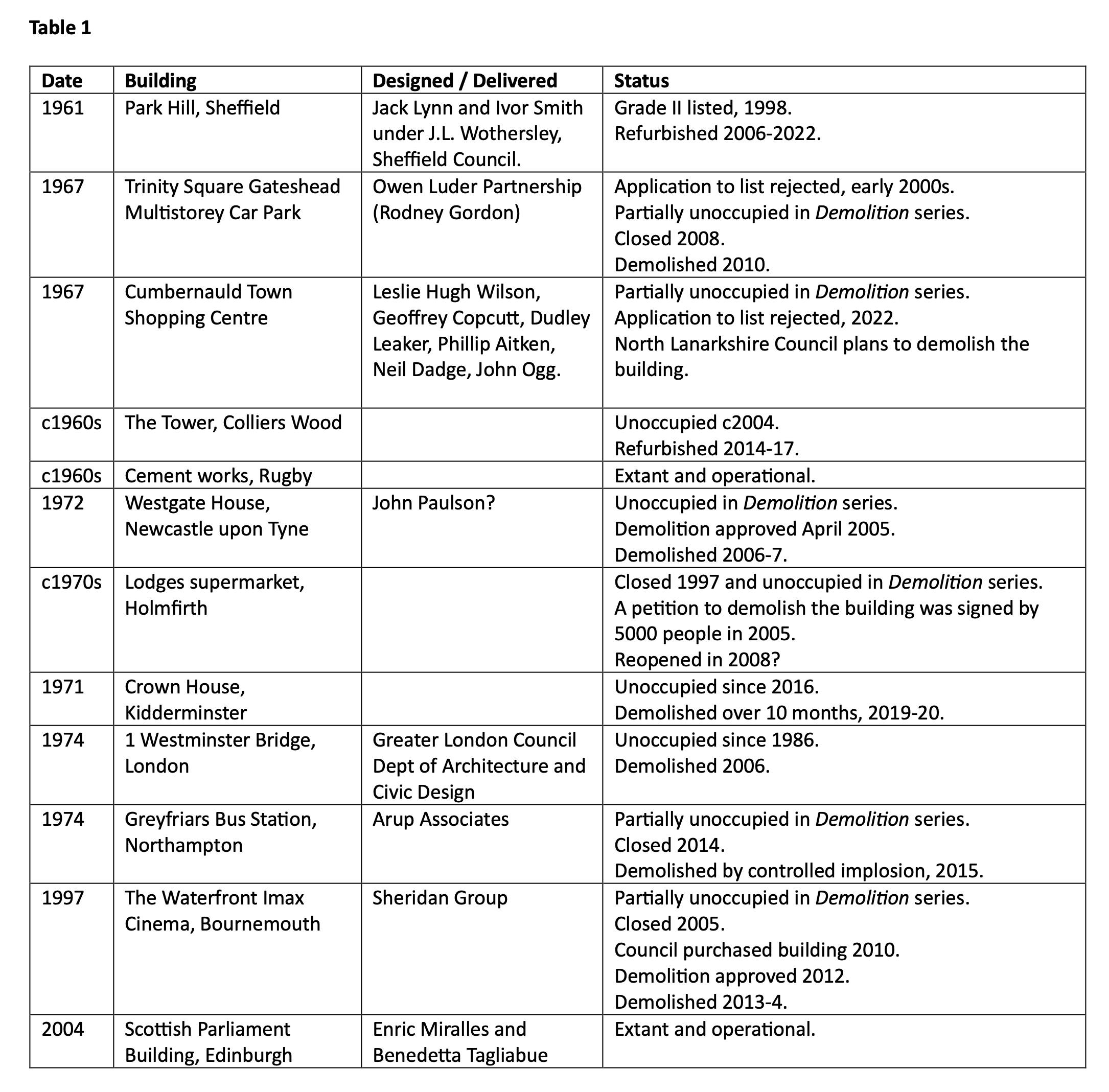

In the lead up to its broadcast, Channel 4 invited the public to nominate Britain’s ‘most hated’ buildings that they would most like to see ‘razed to the ground’. Over 10, 000 people voted, and from this survey a short list of 12 buildings was generated, named the ‘dirty dozen’ (fig. 2)12. A longer list of 35 buildings was published on the website accompanying the series, and the series also featured a wide range of additional buildings that had garnered votes and that related to the themes of each episode.

Most of the dirty dozen were constructed in the 1960s and 1970s. Their prominence exposed the widespread disdain the public held for many buildings of this era, and, as the series would go on to reveal, the schism between this populist view and the view of the design experts that sought to defend their worth. Two iconic examples were the arresting exposed concrete Trinity Square carpark, Gateshead (Owen Luder Partnership, 1967) and the equally bold Park Hill estate Sheffield (Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith, 1961)—new building types that were intended to symbolise a new inclusive and optimistic social order in the postwar era. Others were government and commercial office buildings that applied modern planning ideas and construction techniques, not always with grace or flair. This included several government buildings such as Crown House, Kidderminster (1971) that once housed Inland Revenue, and 1 Westminster Bridge, London (1974) that was home to the Greater London Council until it was dissolved in 1986, reflecting how the expanding bureaucracy of the welfare state became a casualty of neoliberal reform in the following decades. Many of the dirty dozen were already the subject of local campaigns of one sort or another, either to list or demolish, and so already had the attention of their local communities. Outliers in the dirty dozen were the Imax Cinema, Bournemouth (1997) an unsuccessful commercial development that impeded public access to the waterfront, colourfully described by Street-Porter as “literally mooning the people of Bournemouth13” and the newly completed Scottish Parliament (Enric Miralles and Benedetta Tagliabue, 2004), a protest vote registering public outrage at the cost overruns on that project widely reported in the media, but also how this new form of civic building fell short of public expectations. Park Hill Estate, influenced by Le Corbusier’s Unite de Habitation (1952) and the unbuilt Golden Lane competition scheme by Alison and Peter Smithson (1952), was the only heritage listed building to make the dirty dozen. It was Grade II listed in 1998 and has since become an exemplar of modernist housing renewal.

Only one of the dirty dozen had already been approved for demolition: Westgate House, Newcastle (1972). Its design was explained by McCloud as part of a larger modernist renewal planned for the centre of Newcastle, from which only this building was realized (fig. 3). Its incompatibility with the surrounding gothic and Victorian buildings was highlighted, with McCloud describing its situation as “looking like its crashed through … from up the hill, and just skidded to a halt half way across this square, completely destroying the sweep of all those facades14”. The opening of the first episode of the series featured George Ferguson taking a sledgehammer to one of its interior glazed walls (fig. 4)15. The sensationalist premise of the series to showcase demolition was hinted at in this moment, as was the attendant voyeurism associated with the reality television genre more generally. Yet it also disguised how little building demolition was ultimately depicted across the series, and the extent to which it utilized many of the conventions of the authored documentaries about the built environment that preceded it, relying as much on expert commentary, historical footage and didactic exposition, as the depiction of demolition.

But could the threat of demolition really improve what gets built? The critical response at the announcement of the series reflected the predictable difference between popular and expert taste that underpins much reality television about design. Architecture critic Deyan Sudjic was incredulous at the philistine premise of the series:

[t]o suggest that dynamite is the enlightened planner’s best friend is to take us straight back to the mentality that produced so many of Britain’s worst buildings in the first place16.

The Twentieth Century society pre-emptively stated:

[w]e are disappointed that George Ferguson prefers to fuel a populist campaign against architecture, rather than contribute to an informed debate. … An X-list is not going to solve issues of poor town planning or maintenance17.

However, the series ultimately included a diverse and sophisticated cohort of expert commentators, including Catherine Croft from The Twentieth Century Society; Elaine Harwood from English Heritage; Paul Finch, then editor of The Architectural Review and Joanna Averley from the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE). Yet if the series traded on the clash of popular and expert taste, it equally challenged assumptions about the diminished relevance of television as a consensus medium.

A key theme in the theorization of television, has been its dual role as both a public and private medium. It has been defined as marking a distinct shift from the broadcast media that preceded it. Largely contained to domestic interiors, it nonetheless became a dominant form and prime determinant of popular culture in the postwar decades, and televisions themselves also had a parallel life in the public spaces of commerce and leisure. Its critical potential as a medium has at different times exploited this dual identity as both a public and private, and a broadcast and participatory medium18. The persistence of television in the digital age has brought forth hybrid platforms where television became a “mothership” for “ all kinds of cross-media content”, which have continued to challenge the assumption of television’s impending obsolescence19. The introduction of audience voting in the reality television genre brought a participatory element that allowed the co-creation of cultural content20. Demolition was made at the cusp of this digital disruption. Its use of digital media to promote civic engagement in built environment governance was a parallel dimension to the series that sat alongside the audience voting that otherwise threatened to result only in a populist account of the quality and worth of the built environment.

The emergence of reality television also marked a shift in the factual entertainment genre, in which authoritative presenters directly addressed audiences in a traditional documentary style, to the presentation of real-life situations with real people rather than professional actors21. It opened new avenues through which to engage audiences, as well as the built environment as a subject. Channel 4, a public corporation of the UK’s Department of Culture Media and Sport, has a long history of programming design and built environment content22. However, as noted by critic Jonathan Glancey, it is “not easy to make TV programmes about buildings: they’re big, they don’t move around and they never have fights with each other23”. Glancey was reviewing the television series Shock of the Old (Channel 4, 2000), which manufactured controversy by focusing audience attention on how radical, now familiar buildings were, at the time they were first built. It riffed off the earlier Shock of The New (BBC, 1980) an eight-part documentary series on modern art presented by Robert Hughes that, in turn, borrowed heavily from Kenneth Clark’s iconic series Civilization (BBC, 1969), in its genre and authoritative tone.

Changing Rooms (BBC, 1996-2004), the do-it-yourself home improvement television series, was an early example of reality television that cemented the aspirational lifestyle make-over sub-genre. Grand Designs (1999-present) has since become a benchmark example. Hosted by Kevin McCloud, it brought a new informality and entertainment quality to the genre, that nonetheless aspired to continue the educative function of earlier examples of authored documentaries. In Grand Design, McCloud follows owners on their building design and construction journey and provides a critical evaluation of the completed houses spoken directly to the camera at the conclusion of each episode. Often these evaluations validate wider social and ecological benefits of good design, alongside any discussion of the functional and aesthetic qualities of the house. As Stead and Richards have analysed, the programme’s performance of the valuation of good design has the effect of mediating public taste24. McCloud himself recognises this aim, stating:

[i]f Grand Designs can do anything, it can at least raise the level of our awareness and especially our expectations of the quality of the buildings we live in25.

As the main presenter of Demolition, McCloud brought to it his affable expert persona and a similar ambition to mediate public taste. He was quick to declare, however, that the series wasn’t “just about architectural taste” but also about “buildings which actually damage our lives and blight our communities.” At the start of the series, he pointed out that “since the second world war we have built more buildings than the previous thousand years” and the series goes on the reveal not only the low quality of so much of this construction, but also how derelict buildings had become a feature of modern cities, with nine of the dirty dozen partially or fully unoccupied. The Demolition poll had highlighted “the national scandal of thousands of derelict buildings which have been left to rot26”.

The first episode of the series introduced the dirty dozen, with expert commentary on their history, aesthetics, quality of construction, and the logistics and cost of their potential demolition. The following three episodes focused on specific building typologies and themes. This is where the series is most like an authored documentary, constructing arguments of the relative value and worth of each building, and the range of factors that shape the built environment. Episode two ‘First Impressions’ focused on transport and civic buildings that were meant to welcome people to their towns and foster civic pride. This episode revealed the financial and planning exigencies through which many buildings had been left unoccupied, with no incentive to maintain or improve them; as well as the challenge of identifying the intrinsic worth of buildings, especially those that had fallen out of fashion or repair27. Episode three ‘No Place Like Home’ focused on the apparent failure of modernist housing blocks, but also examined the relative quality of subsequent attempts at mass housing provision including mock-historical estates such as Poundbury that nonetheless offered good standards of space and construction; an example of new speculative housing described by Street-Porter as a ‘Noddy estate’ that compromised on the size and quality of individual houses to achieve higher density; and attempts to regenerate abandoned terrace housing stock in the north of the country28. Episode four ‘Cumbernauld Town Centre’ tackled the besieged megastructural Scottish new town completed in 1967, and the strongly divided views about its worth. To move beyond the intractable debates about whether to keep or demolish the complex, it invited a team of architects and urban planners to propose a new plan for the deteriorated town centre. The regeneration of Birmingham city centre was examined as an alternative town centre model that employed a selective demolition strategy and prioritised public accessibility and activation29.

In parallel with the series, Channel 4 hosted an interactive website providing supplementary content and an interface for audience engagement30. The web platform provided an additional means for the mediation of public taste and expert evaluation beyond the series itself (fig. 5). Voting in reality television often manifests as a form of self-interested populism with no relationship to an idea of the public good. However, in Demolition, it also presented as a form of civics, in that it made visible the civic responsibility of managing differentials in taste and expertise in built environment governance.

A follow-up episode, Demolition: What Happened Next, which screened in 2006, was more explicit in exploring the potential of reality television as a civic medium31. This episode tracked McCloud, Street-Porter and Ferguson as they attempted to develop the X-listing proposition into a workable policy. In this sequence there is a literal transposition between voting in reality television and the ambition for greater civic engagement in built environment governance. This is when Demolition is most explicit in promoting civic responsibility and the public good above individual self-interest.

Through its interrogation of each of the dirty dozen Demolition certainly opened a discourse about built environment quality. However, the series did not present a simplistic clash of opinion that might be expected from the reality television genre. The inclusion of building owners and residents introduced a diversity of authentic viewpoints to powerful effect, particularly to demonstrate how invested people were in their built environments. When popular opinion clashed the expert’s views, it was mediated by the presenters. Commenting on 1 Westminster Bridge, London (1974) one person said: “I think the impression this makes of London is that we don’t care”, while another said: “My heart sinks every time I see this building”32. In contrast, Twentieth Century Society representative Catherine Croft suggested that:

I think its got a lot going for it. …It’s a pretty strong sculptural building. What’s wrong with it, is its been neglected. Its been boarded up and empty for years. There is lots of scope for making it an exciting new building. I don’t think it will happen because there are enormous financial pressures to put something larger on the site. … its all too easy for people to be very rude about this building and then be willing to accept something second rate in its place. I’m partly speaking up for this building, because I really want to push the standards very high for this site33.

McCloud’s role in this sequence was to mediate between the opposing positions and challenge passers-by to question the quality of the building intended to replace 1 Westminster Bridge, ultimately concluding that “I don’t think this [new] building has got what it takes34.

Often there was consensus between expert viewpoints and popular opinion around the poor quality of many late-modernist buildings, however demolition was not assumed to be the only solution. Throughout the series the merits of demolition, the risks of demolition without due process, and the relative pros and cons of an X-listing system were extensively debated. Crown House, Kidderminster (1971), which was presented in episode one as an unfortunate outcome of the exemption from planning permission that applied to central government buildings, is also used as an example of a concrete tower where alternatives to demolition could be considered. Architect Ian Simpson suggested that you could “take off the whole envelope … and strip it back to the frame … introduce different levels of glazing, double skin for insulation and animation. Its viable and it can happen. It's happening in other cities. It changes the perception of a building and increases value35".

Similarly, there was a reluctance to condemn all the 1960s and 1970s buildings identified in the audience survey, just because some of them were judged to be bad. After having been shown all the nominations of 1960s civic buildings, Harwood cautioned:

I would be reluctant to demolish many of these buildings, particularly when you see the materials that they’re made of and the craftsmanship that goes in to the interiors and the tremendous sense of civic pride that you see as soon as you step inside many of those buildings36.

At times the lack of consensus between popular and expert viewpoints was used to suggest, somewhat condescendingly, the need for improved design literacy as a solution to the problem. In a discussion about the Scottish Parliament in episode two Ferguson lamented the lack of design literacy in the UK, but also regretted his own failure to convince the surveyed passers-by of the merits of their new parliament building37.

The accompanying web platform provided more opportunities for considered and in-depth argumentation beyond the initial populist voting and confrontations that otherwise propelled the series. This included a more explicit defence of the aesthetic value of brutalist architecture from Liane Jones:

Brutalism took off in this country in the aftermath of the Second World War, when Britain faced a huge rebuilding task. At the heart of the movement was a vision of cities in the sky … Concrete was the new wonder-material. Planners and politicians liked it because it was cheap and quick; architects used it to create sculptural, flowing shapes, and revelled in its rough, raw texture. … The leading brutalist architects … wanted people to experience space in a new way. … to bring the senses alive … [and] encourage a new kind of socialising – warmer, less formal and class-bound. The brutalist dream was a profoundly democratic one38.

The web platform listed resources for citizens to become more active in advocating for better quality environments in their local areas including links to resources on professional and government initiatives promoting good design such as CABE and Better Public Buildings, tools for communities to assess the quality of their neighbourhoods such as Place Check, information on heritage campaigning, and platforms facilitating building salvage39.

Beyond the fate of the featured buildings, the series also encapsulated the tensions that persist in the culture wars in the UK, where demolition has been wielded as a kind of weapon. Street-Porter was one of many perturbed by Prince Charles’s opposition to contemporary architecture in the 1980s, most famously articulated in his speech to the RIBA on 30 May 1984 in which he critiqued a proposed extension to the National Gallery as “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend40”. For Janet-Street Porter, Demolition presented an opportunity to challenge the conservatism in design of the built environment since the carbuncle speech, but also the hegemony of the heritage industry that had otherwise taken root in the UK.

Yet, if demolition has become a weapon in the culture wars, its battlelines have never been neatly drawn. Cumbernauld Town Centre (1967), which featured in Demolition as the worst building in Britain, is an example that illustrates the strong difference between popular and expert taste that was also evident in the critical reception of the series. Designed by Leslie Hugh Wilson and Geoffrey Copcutt, Scotland’s fifth new town was distinctive for its monumental expression of the integrated urbanism that was at the heart of the new town idea. Cumbernauld has been recognised as one of the most significant monuments of Scotland by DoCoMoMo41. It was also the recipient of a Carbuncle Award in 2001 and 2005, an award for the most dismal town in Scotland inspired by Prince Charles’s speech42. In Demolition the building was presented as a case for adaptive reuse rather than demolition, even though it was so disliked in the community. The fate of Cumbernauld has continued to spark volatile debate and remained unresolved for almost 20 years after the series aired. The fate of the building has come to a head with a recent application to list the building being rejected by Heritage Environment Scotland in 202243. Architectural historian Barnabas Calder described the decision as “cowardly and wasteful”, he said: “[i]t's had a hard life, but it's enormously important as an urban experiment44”. Rowan Moore captured the heated debate surrounding the decision: “welcome to the culture wars as applied to architectural heritage” he said, ‘[i]t’s The People v The Experts, the caricature goes, a case of long-suffering locals being told by outsiders that they have to live with an architectural cadaver. Rightwing media outlets and fury factories crow over this ‘massive gulf’ between popular and professional taste45”. In seeking to cut through the debate, and after visiting the building and speaking with locals, Moore ends up on the side of the community: “[a]s an architectural critic, I’m usually on the side of embattled brutalism, trying to point out virtues concealed by neglect. But not this time – the building’s magnificence seems irrecoverable and its problems too blatant46”.

The demolition of modernist housing estates has become a particular lightning rod in the culture wars in recent years. The selection of Park Hill estate for the Demolition series was a relatively safe choice, given its listed status, and its renovation has since become an exemplar of modernist housing renewal, shortlisted for the RIBA Stirling Prize in 2013. Despite this and other successful examples of housing estate transformations, there have been several high-profile destructions of housing estates in recent years47. Joe Mathieson and Tim Verlaan have argued that the destruction of this built legacy is part of a wider ideological contestation48. In this argument demolition becomes a cultural mode of devaluing the legacy of social housing and the welfare state rather than necessarily a marker of obsolescence or changing taste.

Through its engagement with what McCloud termed ‘marmite buildings’—those that people either love or hate, like Cumbernauld and Park Hill—Demolition captured the persistence of the paradox of what to do with buildings that are both loved and hated, good and bad, which has otherwise been co-opted in the culture wars.

A radical part of the premise of the Demolition series was its focus on the poor quality of the public realm. It argued that as individuals we should care about and take responsibility for the design of all buildings and not settle for when they are bad, dysfunctional, or ugly. This is an important point of difference with aspirational lifestyle reality television programmes such as Grand Designs, and its valuation of good design in the domestic realm of the private house. Not all the identified buildings in Demolition were strictly public. However, they were all recognised as contributing—negatively—to the experience of the public realm. While undoubtedly appealing to our “contradictory attachment … to eyesore buildings49” ,the series thus validated an expectation of high quality in the built environment beyond the private houses. As explained by McCloud: “Having a say in what surrounds us can bring a sense of civic pride and wellbeing50”. If the reality television genre introduced a form of performative valuation of good design, Demolition pursued a similar aim through the evaluation of bad design, but also by more explicitly connecting the quality of the built environment with civics and enfranchisement.

The impact of poorly designed buildings was also the topic of the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE) report The Cost of Bad Design that was published in 200651. CABE was established in 1999 to bring independent expertise into built environment governance processes and to raise its quality, a widely agreed problem in the UK52. The report lamented the struggle to have an impact on built environment quality only by focusing on the merits of good design, and it sought to affect change by highlighting the wider impacts of bad design, stating:

[b]adly designed places impose costs on their occupiers, their neighbours and on society. A key reason why these costs are often not taken into account is that they are not paid by the people that make the decisions but by the wider community53.

The demolition of the 1970s system-built Holly Street housing estate in Dalston that was demolished after only 20 years was used to demonstrate the economic and material cost at stake in bad design (fig. 6). It highlighted how building demolition could be understood as symptomatic of an ineffective built environment development system, and conversely, how building demolition could be avoided through more careful investment and consideration of design quality, and higher expectations of developers and owners for building quality and stewardship.

CABE featured as one of the key sources of expert commentary in the Demolition series, with McCloud describing the organisation as “the nations watchdog”54. CABE representative Joanna Averley played an important role in the evaluation of the dirty dozen throughout the series and made a prominent contribution to the Cumbernauld re-design panel in episode four and the panel put together to advance the X-list proposition as a workable policy in the follow-up episode. Like English Heritage, CABE was an independent government agency set up to improve the quality of the built environment largely through advisory and advocacy processes rather than legislation, and with a focusing on new construction rather than heritage. It introduced a peer-based design review process for new buildings in the UK that became one of its key governance tools. CABE’s design review processes enacted a situated form of design evaluation that involved a range of experts and stakeholders and was not unlike the building evaluations performed in Demolition. The sequence discussing Greyfriars Bus Station Northumberland, one of the civic buildings from the dirty dozen that was unequivocally judged to be a failed building, provides an example. Here, the role of the expert presenter was to validate the public’s position that the building should be demolished, and advocate on their behalf to the building owners and planning authorities. Designed by Arup Associates and completed in 1976, the building combined a bus station and depot with associated shopping areas, carparking, and three levels of commercial office space. Its form is described disparagingly by locals at the beginning of the sequence as “two upside-down skips” sitting atop a “gateway to hell”55.

Arriving at the bus station, McCloud proceeded to guide the viewer through the building, highlighting its innumerable shortcomings: “[t]he station is far from user friendly. Arriving here is a confusing and bewildering experience.” Eventually he navigates through a convoluted series of corridors and stairwells only to exit below ground in the shadow of the building (fig. 7). His evaluation of the building focused on its dysfunction and dereliction as much as its ugliness:

Its hard to convey just how vast this place is. Its not built on a human scale. … it dates from a time when expressing big ideals like putting transport interchanges at the centre of the urban experience was much more important that designing for human beings. … The subways were meant to keep people safe and away from cars at street level. But it now has the opposite effect. People avoid the subway and cross where they’re not supposed to. […] Not only is this place dark, depressing and dingy, its also dangerous! So why is it still here?” McCloud goes on to explain the situation: “Northampton Burrough Council owns the building but don’t have the money to demolish it. They’re waiting to sign a deal with the private sector to get rid of the bus station and redevelop the site. But after almost ten years […] nothing has happened. In the meantime, the station has fallen into disrepair. No one wants to spend money on a condemned building56.

Janet Street-Porter then visited the offices of the Council to confront Councillor Phil Larratt. Her frustration at the bureaucratic stalemate that has left the building in a holding pattern between redevelopment and demolition is palpable: “[w]hy don’t you stand on a platform that says to the people of Northampton: I […] promise you that I will sort out this disgraceful bus station and don’t re-elect me if I don’t get it sorted out.” She elicits a commitment from Larratt that the building will be demolished within a certain timeframe (fig. 8). He patiently explains the complexity of putting together a proposal to relocate the bus station and engage a developer to redevelop the site: the building “wasn’t always owned by Council [and] was occupied until recently. […] We’ve had to deal with it in a pragmatic and practical way.” Nonetheless Janet Street-Porter solicits a promise that the building will be demolished within five years57. Famous last words. X-listing was introduced at this moment to offer an alternative to the impasse. McCloud proclaimed: “[i]f implemented, X-listing would offer government incentives to both public and private sectors to speed up the whole process. Bad buildings [could be] redeveloped or removed” (fig. 9)58. The bus station was eventually demolished by controlled implosion in 2015.

Beyond their exaggerated scorn at the terrible state of many of the buildings they visit, the expert presenters also play an important role in contextualising the buildings, presenting additional information about the history of their designs, their histories of ownership and occupation that have in many cases led to neglect and dereliction, and explaining the factors that are impeding remedial action. In doing so they highlighted the complex interconnected reasons for building dereliction or failure, including economic and political ones, just as the CABE report did. They also introduced alternative paradigms through which to understand the buildings beyond a simple evaluation of their aesthetic merit; and an ambition for a better standard of quality in the built environment more generally.

On the website McCloud teased out the importance of looking beyond the current state of the buildings to understand their intrinsic worth, and to restore and remodel where possible: “Buildings can fail because they’re designed badly and without conviction, because they’re superannuated or just because they haven’t been maintained properly. But that doesn’t mean to say we should demolish every failing building in the country. Sometimes the affected structure can be healed rather than amputated.” The Trinity Centre Car Park, Gateshead Newcastle (1967) is discussed by McCloud as an example where there were strong historical arguments to retain the building despite its challenging brutalist aesthetics and poor state of repair.

[d]espite it being loathed by almost every resident of Gateshead […] I don’t want to see it come down. It’s the last remaining work by architect Owen Luder […] and despite its dire need of repair, poor construction andcompromised design […] it remains about the most exemplary car park of its time.

He also pointed out:

[t]here is another good reason to keep the car park of course, which is that it’s now owned by Tesco. If it is ever demolished it will almost certainly be replaced by a supermarket […] I’ll bet whatever gets constructed in its place will look just as, if not more ugly than what’s there now. And I very much doubt that in 50 years time people will be arguing to keep that59.

Episode four on Cumbernauld Town Centre demonstrated how a design review panel might work to improve the quality of the complex60. In this episode, a panel of experts sought not only to evaluate the design of the building, but also to explore ways to overcome its deficiencies and the stalemate over its future. The panel included Mike Taylor, urban planner from Birmingham; Tim Stoner, a pedestrian movement specialist; Andrew Burrell, an architect-developer; architects Gordon Murray, Gareth Hoskins and George Ferguson; and CABE’s Joanna Averley. This sequence revealed the exigencies that impact decision-making about the built environment that might otherwise be opaque to the public, including intersecting levels of bureaucracy, the power differentials between different stakeholders, and the ownership structures that are often antithetical to community needs. The panel also generated alternative development scenarios that considered the partial retention and refurbishment of the complex. Although not presented in these terms, this interrogation of Cumbernauld has much in common with the use of design review processes to improve built environment outcomes adopted by CABE.

The follow-up episode Demolition: What Happened Next was more explicit in linking civic participation with built environment governance61. In this episode an expert panel convened to develop a proposition to implement the X-list idea as a workable policy that could inform planning legislation. As the discussion unfolded, the prospect of an X-list policy is revealed to encompass similar challenges to those faced by heritage instruments, including the need for qualitative assessment, to manage the interrelationship between public consultation and expert decision-making, and the contested and sometimes divisive nature of outcomes. Their blueprint for X-listing included three key points: that anyone could nominate a building; a review panel that included members of the public would consider whether a building should be shortlisted; but the final decision would be taken by experts. To be X-listed a building must have no aesthetic or architectural merit, must have failed economically, and must have a demonstrable anti-social effect. X-listing would prompt remodelling or demolition. Paradoxically, against these criteria, several of the dirty dozen would not have been X-listed. This episode culminated with McCloud taking the X-list proposition to Downing Street and literally knocking on the door of No.10 to deliver it to the Prime Minister. In this moment McCloud is not an expert advisor or mediator of public opinion, but an informed citizen engaging in grassroots action, just as any one of us might.

Throughout the series the X-list model is likened to heritage legislation, and this is how it is developed in the final proposal. However, the Demolition series itself, demonstrated another way to think about built environment governance focused on an enfranchised public having a stake in the quality of the built environment and the capacity to recognise and sanction effective design evaluation. This is the unexpected and more powerful subtext of Demolition.

If the question of what buildings to keep has become the proper subject of heritage and conservation, the naturalisation of demolition has opened a space for its recuperation in architectural theory. Ferguson’s X-list proposition exploited this operative theorisation of demolition while also trying to overcome the dominance of the speculative economy of property development. In Demolition the concept of X-listing and heritage listing are revealed to share an ethos of selective cultural valuation of the built environment, however conservation and demolition also emerge as more complex phenomena of urban change.

In Buildings Must Die: A Perverse View of Architecture, Stephen Cairns and Jane M. Jacobs recognize the paradox embedded in the claim that demolition is a hidden pre-condition of all architecture. Partly, they say, this is to do with how demolition has been mediated as a concept in architecture, between the “bad name given to demolition by earlier instances of architectural erasure […] [and] the circumspection around demolition enforced by built environment preservation62” which has produced an enduring tension between creative destruction and cultural valuation. As Cairns and Jacobs point out, Ferguson’s X-list sought not only to reclaim demolition as an operative design tool but also to denaturalize the development conditions of the built environment, by targeting “the building suspended between use and disappearance. […] [t]rapped within the temporal pause that speculative developers routinely impose on the built environment63”.

In Subtraction, Keller Easterling observes that “most buildings trigger a subtraction of some sort. As marketers, financial experts, planners, and politicians develop buildings, they also detonate buildings and landscapes. […] [yet] when building is the only proper, sanctioned event, there is no platform in place for constructively handling the deletions that reasonably or unreasonably accompany building”.64 He goes on to argue for an economy of subtraction, a deliberate practice of unbuilding not dissimilar to Ferguson’s X-list proposal, he says: “a subtraction economy that removes buildings must also deploy active forms. […] [it] might even significantly alter longstanding cultural habit of regarding buildings as financial instruments with the flexibility of currency.”65

Ferguson’s X-list can also be linked to Rem Koolhaas’s manifesto Preservation is Overtaking Us in which he highlights the potential dilemma of preserving everything, as the temporal distance between the present and what is considered for historical preservation continues to decrease66. Another version of what worried Street-Porter. Instead, Koolhaas seeks to liberate preservation from criteria of historical or cultural value. He points out that “preservation is not the enemy of modernity but actually one of its inventions. […] modernization raises, whether latently or overtly, the issue of what to keep. […] Maybe we can be the first to actually experience the moment that preservation is no longer a retroactive activity but becomes a prospective activity67”. Jorge Otero-Pailos’s accompanying essay emphasizes the “unnaturalness of preservation68”. He explains that “[f]or Koolhaas, the deregulation of the market economy initially made it impossible to practice […] [any] sort of socially committed architecture, and now, more disturbingly, it is eliminating evidence that such architecture ever existed, as this legacy falls victim to development pressures to demolish it69”. Yet, it turns out Koolhaas’s manifesto is as much about demolition as it is about preservation, as evident in OMA’s Barcode preservation scheme for Beijing, which “dispassionately” articulates zones or bands to “either be preserved forever or systematically scraped70”. Like Ferguson’s X-list, it nonetheless turns the task of conservation into one that attends as much to the question of what to destroy as what to keep, and further asks, how can this be governable?

However, the decommissioning and removal of buildings is rarely straightforward or immediate, and not always spectacular. The promise of demolition of the dirty dozen remained largely unfulfilled in the series, except for the performative demolition of some internal fabric of Westgate House in episode one. The visual spectacle of demolition was often provided through the demolition of related buildings and the use of stock footage71. Episode one concluded with the demolition of a 1965 Police Box in Brighton to make way for a public park. Episode two incorporated timelapse footage of the demolition of derelict Sheaf House in Sheffield and its replacement with Sheaf Square—an example of urban regeneration supported by EU funding that enabled the reclaiming of private property for public space. In episode three, Oxgang Towers, a 1960s highrise housing block in Edinburgh that employed innovative prefabrication techniques, was demolished after years of campaigning by residents. This is the Pruitt-Igoe moment of the Demolition series. There were cheers and tears as the building imploded and two residents reflected on their emotional responses. Mandy Lindsay reflected: “I thought I would be more pleased, but actually, I’m a bit sad as well. I didn’t think I would be. Its hard work. I don’t know why I’m feeling this. But a lot is going on in these flats.” Heather Levy expressed similar conflicted emotions:

[There are] a lot of memories. […] I can’t believe how upset I’m feeling. My brother was born there, and he is now dead. It was so loud and it was so quick. Its like all those years have been ripped away, you know. Just like a big grave stone72.

Of the twelve buildings in the dirty dozen, six have since been demolished (fig. 10). In many instances there were years between their demolition and any subsequent redevelopment. The time lag confirms the lack of appropriate incentives to protect built environment quality that Ferguson was reacting to. Westgate House was the most likely candidate for expedient demolition, having already been approved before the series started. However, it was not demolished until 2006-07 after the series had aired, over a period of approximately nine months. Its eventual demolition was included in the follow-up Demolition: What Happened Next.

As with Pruitt-Igoe before it, Demolition is nonetheless a cautionary tale that decisions to demolish buildings should not be taken lightly. The “filmic spectacle” produced at the trial demolition at Pruitt-Igoe likely influenced the future trajectory and eventual demolition of the remaining complex73. Yet the site remained undeveloped for decades. Jencks himself wrote in The Language of Post-Modern Architecture that he thought “the ruins should be kept, the remains should have a preservation order slapped on them, so that we keep a live memory of this failure in planning and architecture74”. As Allen and Wendl discovered, the life of the cleared site after the buildings’ demolition, which paradoxically included being a waste disposal area for other building demolition rubble from the city, extended for a lot longer than the buildings stood for75.

Koolhaas says we are in danger of forgetting “the core lesson of preservation that all things are constantly changing, that once the damage is done, there is no return.” This applies not only to lost buildings, but to the “irreversible consumption of natural resources that was left in the wake of each [period of economic change]76”. This larger tension, between demolition as an operative concept and the often fraught and wasteful demolition of specific buildings, is at the core of the Demolition series. The environmental crisis has demanded more serious reckoning with the wastefulness of a disposable built environment and presents a compelling impetus for keeping more buildings. The question that is now being asked is can the dichotomy of demolition and preservation be superseded by alternative paradigms that emphazise maintenance, repair and care?

The Demolition series certainly exposed how changing standards of public taste complicate the act and meaning of demolition. Beyond this, viewed from today, the series also reveals how expectations and standards for keeping buildings are changing. Sudjic’s incredulity at the premise of the series, was also an objection to the wastefulness of demolition: “[t]earing down buildings before their time is the ultimate in profligacy. Making buildings consumes precious resources and energy and we shouldn’t just throw them away without a struggle to make them better77”. Ferguson’s X-list was an attempt to disrupt normative thinking around the processes of urban development. It also highlighted building maintenance and life-cycle management as a blind spot in built environment governance. Now, it is not simply a question of conserving heritage or making way for better buildings. There is a demand for more careful consideration of the finite material resources embodied in extant building stock. The climate emergency is a new disruptor that demands our consideration of existing buildings as material resources. To not demolish a building is now seen as both a creative and political act78.

Reducing construction and demolition waste has been identified as a specific target within the larger imperative to reduce the energy consumption and waste production associated with the construction industry. As outlined by Lionel Devlieger and others: “[c]onstruction is by far the largest material-consuming activity in the UK. In 2016 the UK produced more than 800kg of construction and demolition waste per person79”. They outline the current existing strategies to reduce waste production, which includes energy recovery (heat production through incineration), recycling and reuse. However, avoiding the premature replacement of buildings and building materials in the first place, is an important preventative strategy. Similarly, new policies are being developed that incentivise building retention and refurbishment80. Heritage governance and management protocols are of relevance in this new policy landscape, offering expertise in material conservation and stewardship of built environments that can be applied beyond listed buildings. The prevalence of 1960s and 1970s concrete framed towers in the public voting in Demolition was a means for Harwood to point out the need to be selective in what is conserved: “to understand the good from the bad and not write off the whole period”. Now such concrete towers are becoming a specific target of refurbishment, and forms of elective conservation81.

Even though environmental sustainability arguments against building demolition have added a new layer to the well-developed cultural and social arguments for conserving buildings, the selective category of heritage listing persists as the strongest tool to protect against demolition driven by property speculation. The Demolition series highlights the role of culture in motivating stewardship of the built environment, not by focusing on the fraught and over-exposed category of heritage, but by challenging our cultural assumptions about demolition. This has relevance now, in relation to the requirement for better understanding of the cultural shifts required to reduce wasteful demolition as a crucial part of the larger objective to achieve net zero carbon emissions.

More provocatively, Demolition raises, but doesn’t resolve, the predicament of keeping things we no longer value, or conversely, valuing things that we ought to keep. Like the first building discussed in Demolition, Westgate House in Newcastle: would it have been a contender for retrofitting if it was not demolished in 2006? Jencks was somewhat prescient when he suggested that we should “value and protect our former disasters82”.

He imagined Pruitt-Igoe as a permanent ruin or memorial. If not that, then we should certainly reckon with and take responsibility, not only for the things we are creating, but for the things we have already made. Demolition reminds us that this is not only a question of design, but also of politics, governance and culture. The revolution may no longer be televised, but there is still a question as to how civic conversations and cultural change will productively take place. As Jencks said: “[t]o change culture, you need to capture public attention83”.

notes

Jencks, Charles. 1977. The Language of Post-Modern Architecture. London: Academy Editions, 9.

R. Allen, Michael, and Nora Wendl. 2014. “After Pruitt-Igoe: An Urban Forest as an Evolving Temporal Landscape.” Studies in the History of Gardens and Designed Landscapes 34, no. 1: 104.

R. Allen, Michael, and Nora Wendl. 2014. Op. cit., 104.

Demolition, 4 episodes, executive producer Nicolas Kent, series producer Kate Middleton, head of production Annabel Lee and Birte Pedersen (episodes 3 and 4), featuring Kevin McCloud, Janet Street-Porter and George Ferguson, aired December 17, 18, 19 and 20, 2005, on Channel 4, UK. I would like to thank the British Film Institute and the BFI National Archive for their assistance in viewing the Demolition series.

Street-Porter, Janet. 2004. “Editor-at-Large: Lord Preserve us from Griff Rhys Jones.” Independent, May 2, 2004.

Street-Porter, Janet. 2004. “Don’t save buildings – demolish them.” Independent, July 22, 2004.

The post-modern townhouse by Piers Gough house was Grade II listed by Historic England in 2018.

Riding, Alan. 2004. “An Essay: A Building Is an Eyesore And Must Go? Grade is X.” The New York Times, Section E, August 30, 2004: 1.

Ibid.

“Ferguson Makes a Modest Proposal.” Building, April 16, 2004.

In 2004 he undertook a tour of the UK to identify “architectural and planning triumphs and disasters” and was “approached by a television company to repeat the exercise next year”. “Ferguson names wonders and blunders on UK tour,” Building Design, September 5, 2003.

Channel 4 described the survey as the largest of its kind. However, 10000 responses was small in comparison with the 2.3 million who voted in the 2003 series of Restoration.

Demolition, episode 2, “First Impressions,” produced by Mark Bentley and Tracey Li, directed by Bindu Mathur, aired December 18, 2005, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen,” produced by Mark Bentley, Rob Daly and Tracey Li, directed by Harry Beney, aired December 17, 2005, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen,” 2005.

Sudjic, Deyan. 2005. “Celebratory demolition? The whole idea stinks.” The Observer, January 2, 2005.

Zeidler, Cordula. 2004. “Should Grotesque Buildings Be Demolished? A reply to George Ferguson and the BBC.” The Twentieth Century Society, August 25, 2004, https://c20society.org.uk/news/should-grotesque-buildings-be-demolished-a-reply-to-george-ferguson-and-the-bbc. Accessed August 30, 2023.

Newcomb, Horace. 2000. Television: The Critical View. Oxford University Press. Jenkins, Henry. 2001. “Participatory vs Consensus Media.” Reconstructions: Reflections on humanity and media after tragedy (blog), MIT Comparative Media Studies, September 16, 2001, https://cmsw.mit.edu/reconstructions/interpretations/particip.html. Accessed September 10, 2023.

Hill, Annette. 2015, Reality TV. London: Routledge, 13.

Ivi, 21.

Ibid.

See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Channel_4_television_programmes.

Glancey, Jonathan. 2000. “Back to the Future,” The Guardian, August 18, 2000. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2000/aug/18/tvandradio.television. Accessed August 28, 2023.

Stead, Naomi, and Morgan Richards. 2014. “Valuing Architecture: Taste, Aesthetics and the Cultural Mediation of Architecture Through Television.” Critical Studies in Television 9, no.3: 99-112.

Kevin McCloud, quoted in Pratt, Steve. 2013. “Building the Fascination,” Northern Echo, October 2, 2013. Available: https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/opinion/latest/10711403.building-fascination/. Accessed August 30, 2023.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen,” produced by Mark Bentley, Rob Daly and Tracey Li, directed by Harry Beney, aired December 17, 2005, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition, episode 2, “First Impressions,” produced by Mark Bentley and Tracey Li, directed by Bindu Mathur, aired December 18, 2005, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition, episode 3, “No Place Like Home,” produced by Mark Bentley and Tracey Li, directed by Chester Dent, aired December 19, 2005, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition, episode 4, “Cumbernauld Town Centre,” produced by Mark Bentley, Rob Daly and Robert McCourt, directed by Lucy Cooke, aired December 20, 2005, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition (website), Channel 4, archived June 15 2006. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20060615193642/http://www.channel4.com/life/microsites/D/demolition/index.html. Accessed June 1, 2023.

Demolition: What Happened Next, executive producer Nicolas Kent, head of production Annabel Lee and Birte Pedersen, produced by Tracey Li and Mark Bentley, directed by Barnaby Peel, presented by Kevin McCloud, Janet Street-Porter and George Ferguson, aired September 30, 2006, on Channel 4, UK.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen”, 2005.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen”, 2005.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen”, 2005.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen”, 2005.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen”, 2005.

Demolition, episode 2, “First Impressions”, 2005.

“To Demolish or Not? I Love Carbuncles,” Demolition (website), Channel 4, archived June 15 2006. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20060826172157/http://www.channel4.com/life/microsites/D/demolition/demolish4.html.

“To Demolish or Not? I Love Carbuncles,” Demolition (website), Channel 4, archived June 15 2006. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20060826172157/http://www.channel4.com/life/microsites/D/demolition/demolish4.html.

See: Wainwright, Oliver. 2022. “Carbuncles and King Charles: was the royal family’s meddling supertroll right about architecture?” The Guardian, September 28, 2022. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/sep/28/carbuncles-king-charles-iii-royal-familys-supertroll-architecture. Accessed August 30, 2023.

The Carbuncle Awards were established by Urban Realm magazine and inspired by Prince Charles’s speech.

Historic Environment Scotland, Cumbernauld Town Centre decision, 23 November 2022. Available: https://www.historicenvironment.scot/about-us/news/cumbernauld-town-centre-decision/#:~:text=Cumbernauld%20Town%20Centre%20decision,-Today%20we%27ve&text=Following%20an%20assessment%20informed%20by,list%20them%20at%20this%20time. Accessed August 30, 2023.

Crook, Lizzie. 2022. “Demolition of Cumbernauld's brutalist town centre ‘a complete outrage’.” Dezeen, March 14, 2022.

Moore, Rowan. 2022. “Rip it up and start again? The great Cumbernauld town centre debate,” The Guardian, April 3, 2022. Available:https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/apr/03/cumbernauld-town-shopping-centre-debate-brutalist-architecture. Accessed August 30, 2023.

Ibid.

The demolition of Robin Hood Gardens (Alison and Peter Smithson, 1972) is an example.

Mathieson, Joe, and Tim Verlaan. “The Far Right’s Obsession with Modern Architecture,” Failed Architecture, https://failedarchitecture.com/the-far-rights-obsession-with-modern-architecture/. Accessed August 30, 2023.

Cairns and Jacobs referring to Mélanie van der Hoorn’s ethnography of ‘undesired architecture’. Cairns, Stephen, and Jane M. Jacobs. 2014. Buildings Must Die: A Perverse View of Architecture. Cambridge Mass. And London: MIT Press, 213.

Demolition: What Happened Next. 2006. Op. cit.

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, The Cost of Bad Design (2006). Available: https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20110118110506/http://www.cabe.org.uk/publications/the-cost-of-bad-design. Accessed August 28, 2023.

CABE was merged with the Design Council in 2011.

Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, The Cost of Bad Design, 7.

Demolition: What Happened Next. 2006. Op. cit.

Demolition, episode 1, “The Dirty Dozen”, 2005.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

“To Demolish or Not? Suitable Cases for Treatment,” Demolition (website), Channel 4, archived June 15 2006. Available: https://web.archive.org/web/20060826040536/http://www.channel4.com/life/microsites/D/demolition/demolish2.html.

Demolition, episode 4, “Cumbernauld Town Centre”, 2005.

Demolition: What Happened Next. 2006. Op. cit.

Cairns, Stephen, and Jane M. Jacobs. 2014. Op. cit., 219.

Ivi, 215.

Easterling, Keller. 2014. Subtraction. Berlin: Sternberg Press, 1-2.

Ivi, 2-3.

Koolhaas received the RIBA Gold Medal in 2004 during Ferguson’s tenure as President.

Koolhaas, Rem. 2014. Preservation is OvertakingUs. New York: Columbia University, 14-16.

Ivi, 98.

Ivi, 84.

Ivi, 17.

The Demolition website also included a section of demolition clips.

Demolition, episode 3, “No Place Like Home,’ 2005.

R. Allen, Michael, and Nora Wendl. 2014. Op. cit., 104.

Jencks, Charles. 1977. Op. cit., 9.

R. Allen, Michael, and Nora Wendl. 2014. Op. cit.

Koolhaas, Rem. 2014. Op. cit., 86.

Sudjic, Deyan. 2005. Op. cit.

Oliver Wainwright has written about new practices that are reworking buildings instead of knocking them down. Wainwright, Oliver. 2022. “’Demolition is an act of violence’: the architects reworking buildings instead of tearing them down,” The Guardian, August 16, 2022. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/aug/16/demolition-is-an-act-of-violence-the-architects-reworking-buildings-instead-of-tearing-them-down. Accessed August 30, 2023. See also the forthcoming book: Malterre-Barthes, Charlotte. 2024. A Moratorium on New Construction. London: Sternberg Press.

Rotor (Lionel Devlieger, Maarten Gielen), Little, Samuel, Roy, Arvind, and Aude Line Duliere. 2019. “Building and Demolition Waste in the UK.” arq 23, no.1: 90.

For example, the City of London’s 2023 sustainability guidance that emphasises a ‘retrofit first’ approach, and the City of Melbourne Retrofit Melbourne policy also launched in 2023. “City of London Corporation approves new sustainability guidance for developers in ‘huge step’ towards net zero,” City of London (website), December 12, 2023, https://news.cityoflondon.gov.uk/city-of-london-corporation-approves-new-sustainability-guidance-for-developers-in-huge-step-towards-net-zero/. Accessed January 29, 2024. Retrofit Melbourne (Melbourne: City of Melbourne, October 2023). Available:https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/SiteCollectionDocuments/retrofit-melbourne.pdf.

For example Zin in Brussels (51N4E, l’AUC, Jaspers Eyers and Befimmo, 2023), the rehabilitation of the World Trade Centre Buildings (Groupe Structures, 1972 and 1983), and the elective conservation of Camden Town Hall Extension (Sydney Cook, 1970) as the Standard Hotel (Ian Chalk, 2019). 51N4E, Chapter 3: How Not to Demolish a Building (Berlin: Ruby Press, 2022). “40 Buildings Saved: 28. Camden Town Hall extension, London,” Twentieth Century Society (website), https://c20society.org.uk/40-buildings-saved/28-camden-town-hall-extension-london . Accessed January 29, 2024.

Jencks, Charles. 1977. Op. cit., 9.

Jencks, quoted in R. Allen, Michael, and Nora Wendl. 2014. Op. cit., 104.

Julia Viallon

Ayla Schiappacasse

Maryia Rusak

Carlo Francini Vanessa Staccioli Gaia Vannucci