The research sought to investigate the Olivetti typewriter company’s generalized loss of identity in the Canavese region, starting from the analysis of the processes that led to the progressive abandonment of the corporate’s architectural heritage in the second half of 20th century.

Under the presidency of Adriano Olivetti (1938-1960), after the second World War the company entered the electronics’ field. Aware of the Italian technological backwardness, the corporate looked at the most technologically developed countries. The role of USA soon became crucial: here Olivetti founded the very first research centre in 1952, followed similar pioneering experiences in Italy where the commitment of Le Corbusier for an electronical centre (1960-1965) marked the apex of this season. The failure of this project reflected the economic and management-level crises that followed the sudden death of Adriano in 1960 and that caused a global corporate’s reorganization.

After the first reluctance of the BofD, new investments were settled for electronics, and triggered the most demanding architectural program in the whole company's history both in Italy and abroad. In the Canavese region – Olivetti’s birthplace that the research aims to investigate – the project of a cultural, political, and economic community – the Comunità started by Adriano in the 1930s – led to a wide improvement of the constellation of buildings dedicated to electronic research, training and production, often followed by facilities.

Nowadays, mostly none of those architectures recalls the name Olivetti. Hardly anything has been said about their dismission, partial or complete destruction that led to an identity’s collapse in the 1990s. This process seems to be even more impactful in those places where the company had its strongest influence, where its buildings – and its legacy – lie as in an elephants’ cemetery.

Among them, the industrial hub of Scarmagno (1962-1988) assumes a crucial importance in this research. Placed in the heart of Canavese, plants, warehouses, offices, training centres, library, infirmary, and other facilities of this new complex were entrusted to internationally known Italian architects, as Eduardo Vittoria and Marco Zanuso. The architects conceived an activities’ container that conveyed space quality, modularity, prefabrication, technological innovation.

Given the chronology and the complexity of its transformations, Scarmagno hub is taken as a paradigmatic example of this phenomenon of oblivion, increased by the recent debate on re-functionalization.

By comparing the documental heritage at Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti (Ivrea, Italy) with the corporate house organs, the recent bibliography on Olivetti corporate history, and local and national newspapers, the study aims at highlighting the gap in the traditional Olivetti tale told by the architectures left after the myth’s fall.

In this contribution1, the permanence of the Olivetti company identity in Canavese – to be considered as a pivotal area of Piedmont located at the foot of the Alps between Valle d'Aosta and Lombardy – is examined through the parable of the Scarmagno production pole. Considered the very heart of the region, it represented a strategic settlement located along the highways to Aosta, Turin, and Milan, about 13 kilometres from the city of Ivrea – Olivetti’s birthplace. Between the 1960s and 1990s, it became a paradigmatic case of the rise and decline of the company’s theories regarding the relationships among production, territory, community, and city. Linked to these aspects is the slow but inexorable process of abandonment and progressive destruction of the buildings, both cause and consequence of the loss of identity in this location, which is especially significant in relation to its proximity to the company's hometown.

In Olivetti’s school of thought, the element of territory was an integral part of a production cycle both directly – through agricultural activities – and indirectly – amid the secondary and tertiary sectors – other than being a catalyst in the processes of social change. These theories had experimental implications in territorial transformations, and, more specifically, the Canavese region became the area of application of community principles. Adopting a systemic approach led Ivrea’s satellites to assume a central role in the region’s overall development. The history of Scarmagno hub is set in this context. Starting in the early 1960s, this area took on the role of “epicentre of social governance of production”2 and represented an experience through which the relationship between planning (urban planning) and programming (economic policy) became directly and immediately explicit.

Olivetti centred its industrial policy around the relationship between the city and the countryside, intending to ensure an alternative growth model – anti-capitalist or post-capitalist – which constitutes a ‘third way’ beyond state socialism and liberalism. In this perspective, urban planning was the privileged discipline, as it ensured the wide-ranging growth of the territory, thanks also to a close interaction with the social sciences3. The instrument of the urban plan – “cathartic journey of reviewing the city and its territory”4 – proved to be crucial as it guaranteed the decentralization of industrial complexes and the occupation of the rural space in order to reformulate the relationship between city and countryside5.

In the Olivettian view, the territory was the “optimum of organisable living space”6 through which the Comunità - the original way to intend the community dreamt by Adriano Olivetti - can express itself and where the planner assumes the role of interpreter of the territory’s needs and head of its growth. According to the professionals revolving around Adriano, the plan had a socio-political value that, on the one hand, followed the guidelines set overseas by the US’ Joint Centre for Urban Studies and, on the other, established a new territorial order based on the principles of Community7. By employing a participatory process, the local community became a reformation cell, moving at several levels and scales, from political representation to land management, from personal affirmation to technological development: “the plans were to be discussed by the Community, formed within the Community, by a Community technical office, controlled by Community political bodies, but discussed within the Community8”.

The area’s expansion was structured according to a precise methodology, imposed both by the attention paid to the inhabitants and by their attachment to the environment9: here, an initial phase of understanding and interpretation of reality was subsequently followed by practical proposals aimed at governing the territory. This analysis-project binomial – which became a distinctive feature of Olivetti’s urban planning culture – found its first application in the Master Plan for Valle d’Aosta. The latter was drawn up between 1936 and 1937 by a heterogeneous group composed of architects, sociologists, and economists and was structured as a template to be used in drafting forthcoming regional master plans10.

The holistic approach employed in this initial study was further taken up and developed in different proposals for Ivrea’s masterplan, where the analysis process gained even more importance through the extensive data and sources provided in the version drawn up by Ludovico Quaroni, Nello Renacco, Annibale Fiocchi and Enrico Ranieri between 1952 and 1954. In particular, regarding the key role of analysis, a dedicated study commission was already founded in 1952: named GTUC (Gruppo Tecnico per il Coordinamento Urbanistico del Canavese), it was set up to support the research in the region, with the final aim of building and managing a production network in the area, operating on the inter-municipal scale of the Eporediese and the sub-regional scale of the Canavese11.

On top of the above strategies, in 1954, Adriano founded the I-Rur (Istituto per la Ricostruzione Urbana e Rurale), an institute that provided technical assistance to private individuals, associations and municipal administrations based on the British Town and Country Planning model. This initiative stemmed from the awareness that the communities in Canavese could not live exclusively off Olivetti nor exclusively off the industry12. It thus represented an effort to develop “an organic plan-project of a different company, a different industrial structure, a different way of producing and working13”.

I-Rur created and financed various productive and cultural initiatives by establishing social industries and autonomous agricultural associations. Thanks to these initiatives, Olivetti became a catalyst in the region for constructing important architecture that turned the community project into a tangible reality. The construction of Canavese silverware factory in Loranzè (Carlo Viligiardi, 1960-1962), the stables of the Agricultural Cooperative in Montalenghe (Giorgio Raineri and Antonietta Roasio, 1957-1958), the Laboratory in Vidracco (1957-1964, 1984) and the Community Centre in Palazzo Canavese (1952-1955) by Eduardo Vittoria, the school complex and the RTM Laboratory in Vico Canavese (Nello Renacco, 1962-1964) are just some of the buildings that represents one of the less striking, but more significant, aspects of the Olivetti global project.

All these operations were developed in conjunction with the activities of the Ufficio Consulenza Case per i Dipendenti (UCCD), an Olivettian department that offers employees free technical assistance for the construction or restoration of their homes, both in Ivrea and in their hometowns, to contain the depopulation of the countryside and the Alpine valleys14.

This articulated structure was designed to spread nationwide by implementing similar projects in contexts different from Canavese, such as Lombardy and Campania. In this way, Piedmont became a testing ground for exploring an expansion model based on integrating industry and agriculture15.

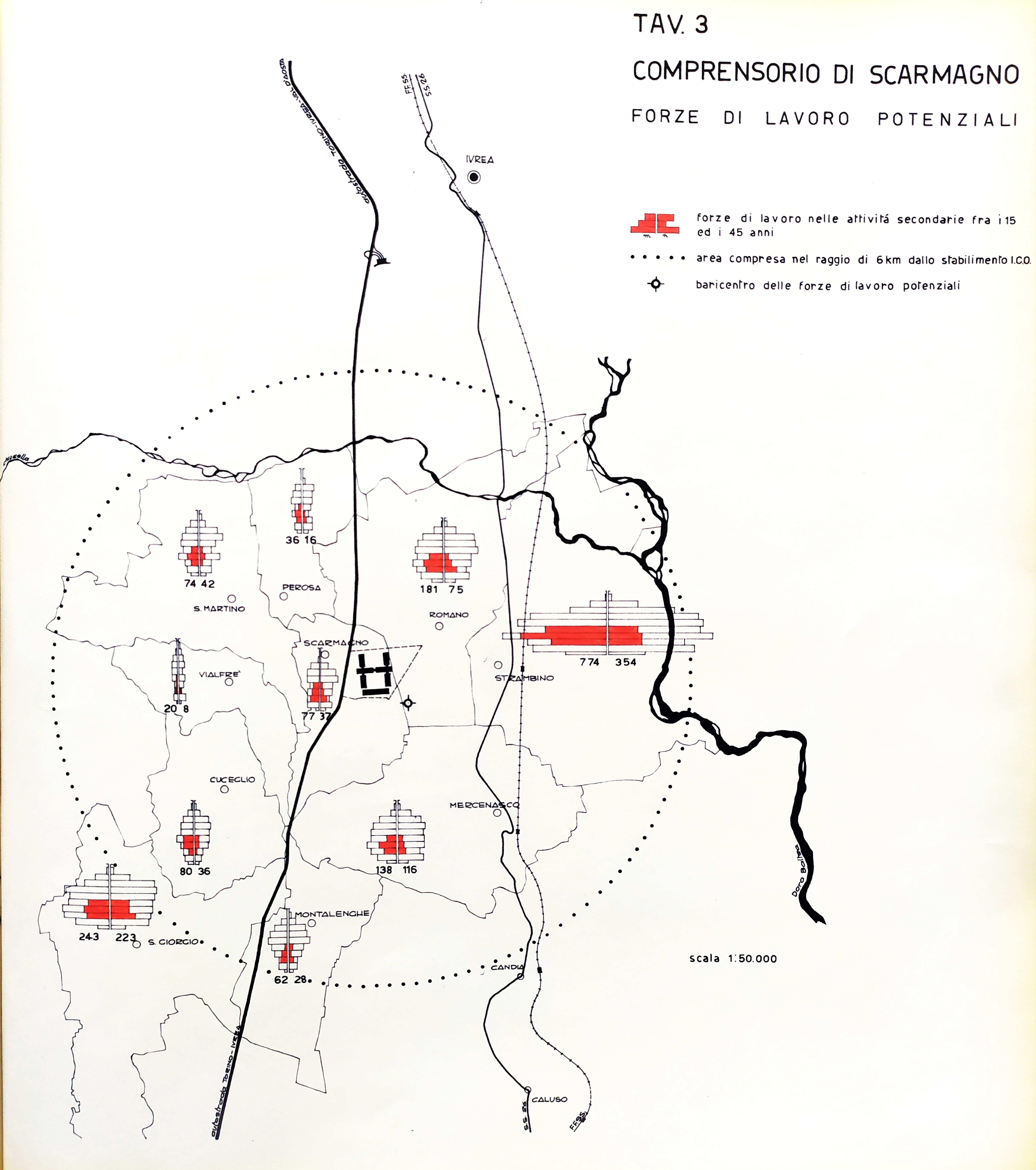

These experiences were reflected in the study and regional development project by Giovanni Astengo in early 1962 for the Scarmagno area, commissioned by the Olivetti company (fig. 1). In particular, Astengo (1915-1990) was one of Italy’s most relevant post-World War II urban planners searching for a scientific approach that welds programs and plans to integrate economic development and intervention planning. His work stood in absolute continuity with the objectives of Adriano Olivetti – of whom he becomes one of the main referents – and widely circulated in Urbanistica, the magazine of which he was the editor until 1977 and where the project for the Scarmagno site was broadly published.

In the cited document, a clear trace of this approach to the territory can be noted both in the method of drafting and in the management and development proposal. The plan did not only consider the area concerned by the new industrial expansion but extended both the preliminary analysis and the planning strategy to a wider pool that includes, in addition to Scarmagno, the municipalities of Romano, Strambino, Mercenasco, Montalenghe, S. Giorgio, Cuceglio, Vialfré, S. Martino and Perosa16.

The analysis – which constitutes the project’s backbone – is divided into three sections that accurately portray the geographical conformation of the territory and the demographic and economic situation through numerical data and illustrative tables. The guidelines for the Scarmagno area arose from the detailed analytical process aimed at understanding this inter-municipal reality, in which the factory constituted the heart of a community that expresses itself through the activities of the I-Rur and the Community Centres.

Despite some internal discrepancies due to conflicting viewpoints of the new board about the social role of the company, this approach attempted to embrace the pure Olivettian vision that considered the factory as an essential part of a larger and more complex environment: the plan drove the process of industrialization and, thanks to its interdisciplinary approach, aimed to avoid impositions on the territory17. This attitude was especially true for the most fragile contexts, in Italy as well as abroad, where the presence of the State was weaker in terms of welfare (Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and South America in general) and where Olivetti advocated a solidarity-based development of the territory18.

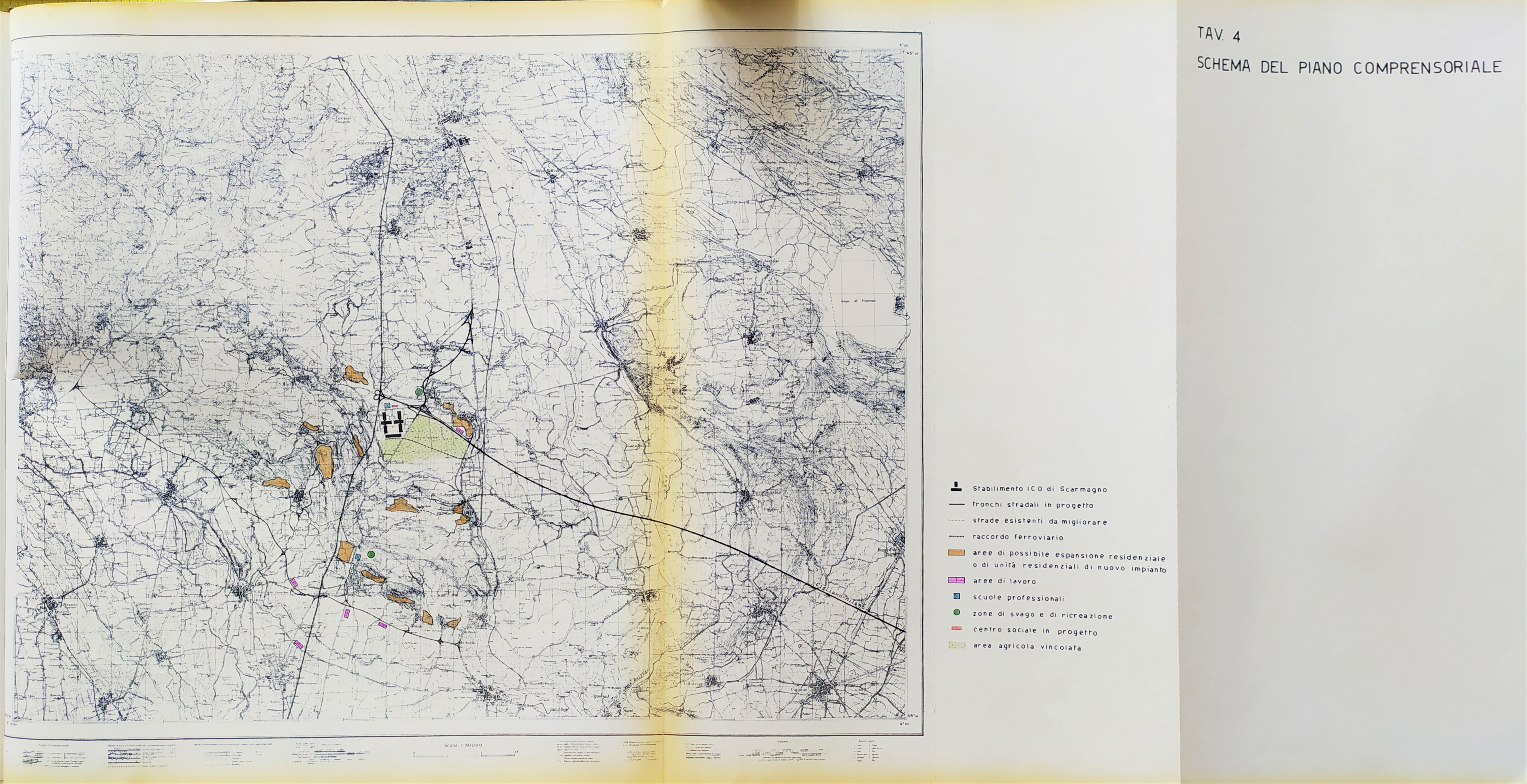

The facilities network provided by Astengo to support the region’s development program considered all dimensions of life, including new infrastructures, work areas, housing, training centres, social services, and leisure areas spread over a 7-hectare area surrounding the factory. In this way, the town planning concept proved to be a tangible embodiment of the Canavese community’s needs and, therefore, assumes a collective responsibility (fig. 2).

The community issues also reach an administrative level. Due to the uncertainty concerning the Sullo town-planning law (1962) and, thus, the impossibility of drafting a district plan, Astengo opened up on the possibility of a consortium between the ten municipalities surrounding the factory area that involves Olivetti and the Province in a larger political project. The attempt to coordinate political activities as a driving force for the territory had already found its earliest experimentation with the creation of the Lega dei Comuni del Canavese in 195519. As a response to the phenomenon of ‘explosion’ of the city experienced by the West of the world in the 1950s – “confused, disorganized urban mass that [...] frustrates and defeats every purpose of city life20” –, the Canavese experiment provided a true alternative to the conurbation problem. The community re-examination of urban densification dynamics as related to the decentralization of productive and civic activities was structured according to the principles of the ‘regional city’ theorized by Clarence Stein in the 1920s. These ideas have been brought back into the Italian debate through studies promoted by Adriano and carried out by Carlo Doglio21.

Within the spatial layout proposed by Olivetti, the industrial plant constitutes the pulsing core and engine of the development process in which the entire conurbation area is involved. Both urban planning and architectural design are affected by the company dynamics characterised by great internal conflict22. Consequently, the architectural project spans almost three decades. The first solutions are proposed by Olivetti’s internal technical department – headed by architect Ottavio Cascio – while the architect Alberto Galardi - recently entrusted with the design of the Marxer Institute, part of the I-Rur orbit - was asked the design for a technical school23.

These projects were followed by the entrustment – apparently decided by Adriano shortly before his death – to Marco Zanuso and Eduardo Vittoria, both protagonists of Olivetti architectural commissions in the 1950s24. The two designers are attentive to the company’s expansion policies and the territory’s potential for progress. Therefore, they conceive a building that panders to the idea of growth highlighted by Astengo’s report.

The original spatial structure – conceived together with engineer Silvano Zorzi and drew on the studies of Kondrad Wachsmann25 – was meant to be in metal carpentry and defined a space based on a multi-scalar spatial device, the ‘module-object’. As explained in the architects’ will, this concept responds to the need for synthesis between landscape, architecture, and design, the three main key concepts on which to set the entire project. In the Scarmagno area, the Olivettian total design concept finds fertile ground. Moreover, at least until 1964, a residential area was planned in the vicinity of the Scarmagno plant26. Indeed, communication with the public takes on a key role. Through the magazine “Notizie Olivetti” – house organ that constituted a bridge between the company and the local community – both parts of Astengo’s study and Zanuso and Vittoria’s report were published in 196227. Thus, the ubiquity of Olivetti’s intervention emerges, which is particularly evident when we analyse how the different scales are co-participants in realising a larger system, that is completely aimed at the community (figg. 3 and 4).

In 1964 the company experienced a new moment of serious crisis: the Olivetti board of directors was taken over by the Intervention Group-formed by Fiat, Mediobanca, La Centrale, Imi, and Pirelli – to which was added the sale of the electronics division. These factors led to a crucial rearrangement of company policy28.

The massive new expansion project confirmed the construction of a production plant in Scarmagno, which, thus, became the model of two other new poles to be contextually built-in Crema (Lombardy) and Marcianise (Campania)29. The three plants were designed and built between 1967 and 1972.

The territorial project of Scarmagno was then entrusted to the Tekne company, run by Roberto Guiducci – a relevant technical and intellectual figure trained at Olivetti company – , who also carried out the plan for developing Marcianise in 1968, and other industrial realities in Southern Italy. The study’s outcome profoundly differed in method and the idea of ‘widespread urbanity’ proposed by Astengo in 196230. The new plan assessed the impact of the factory concerning several systems, from the regional to the inter-municipal scale, the latter already the subject of the previous plan. The plant takes on a wider sphere of influence, which is affected, on the one hand, by the coeval studies conducted by Ires on the Piedmont region31 and, on the other, by the company’s plan to make Scarmagno the great manufacturing hub of Canavese. Here, other industrial activities of the company were to converge, particularly regarding the renewed interest in electronics.

The architectural scale also transformed because of the renewed transition from the mechanical to the electronic sector. In the late 1960s, the introduction of UMI (Unità Montaggio Integrate) – interdependent work islands replacing the assembly line – forced a reconfiguration of the industrial plant layout32.

The company’s ufficio tecnico reworked the structural solution in the first instance. A reinforced concrete system was imposed in place of the original steel one for reasons of economy and speed of construction, while in 1967, the architectural design was again entrusted to Zanuso and Vittoria, who were joined by both Guiducci’s Tekne and engineer Antonio Migliasso33.

The very peculiar and contradictory form of Olivetti’s general intellect, characterised by a capitalist perspective, was supposed to be realised in Scarmagno, where the goal was to foster a “socialisation of productive labour that is increasingly – or definitively – incorporated into scientific and technological research34”.

The same building typology used in Piedmont has been adopted for the new Crema and Marcianise plants, but with a different spatial arrangement of the module-objects (fig. 5). These changes were due to the need to adapt the buildings to production and the landscape. Even in Lombardy and Campania – contexts that radically differed from the Canavese region – an attempt to integrate territory, production and community was implemented. In Crema, the new plant constitutes an expansion of the old Serio factory, flanked by the construction of houses for employees and managers35. In Marcianise, Olivetti promotes the construction of a district of subsidized housing designed and built in collaboration with Iri. This decision stands in direct continuity with Olivetti’s commitment to the Mezzogiorno (Southern Italy) inaugurated by Luigi Cosenza’s Pozzuoli production and residential district (1951-1955).

The final design for the Scarmagno industrial hub may represent the last example of the Olivettian architecture thought to be an “interface of the territory, a new social condenser”36, where even the formal aspect responds to the productive, economic, social, and cultural needs of the territorial community.

Interestingly, the same model of Olivetti’s land management and exploitation during the second half of the twentieth century had different outcomes in different contexts in the long run. This aspect is especially true when considering the process of their divestment. While in Scarmagno and Marcianise, the factories were abandoned during the 1990s, other industrial and manufacturing activities and the University of Milan occupied the Crema buildings37.

In recent years, the collective consciousness has rediscovered the sense of belonging to the Olivettian identity, which increases in strength with distance from Ivrea. In both Crema and Marcianise, several public initiatives aimed at the remembrance of Olivetti have triggered a process of raising awareness concerning the preservation, protection, and enhancement of the buildings themselves (fig. 6)38.

No similar initiatives are recorded in Scarmagno, and this apparent disaffection may have arisen early in the life of the Piedmont area. For example, following the managerial crisis that hit Olivetti in 1964, combined with heavy financial debt and the ‘electronics issue’, the new management blocked funding to I-Rur, which would finally disband in 197239. This interruption of the Olivettian community project had very strong repercussions on the outcomes of the Scarmagno district. Even before its full realisation, the industrial hub was deprived of one of the management and control organs of the many productive and cultural activities that were supposed to constitute the ‘city-region’. Generally, the divestment of Olivetti and I-Rur activities that began in the late 1970s led to a gradual abandonment of the architecture that housed them. Where on the contrary, cultural, artisanal, or industrial activities have been preserved, such as the La Serra social winery or the ICAS sparkling wine cage factory in Ivrea, the distillery of the eponymous bitters in Bairo, or even the Palazzo Canavese Community Centre, identity and belonging to the Olivetti world are still tepidly present characters40. In contrast, in Scarmagno, the abandonment of production, the gradual decommissioning, the vandalization of buildings, or the takeover of other activities have caused the loss of Olivettian memory and identity41.

In addition, between the 1980s and 1990s, the company also centralized its production activities in Scarmagno to cope with new investments in information technology. These conditions led Olivetti to face an increasingly competitive market and a growing need for work automation, resulting in staff reductions42.

The decommissioning and subsequent labour struggles, the burning down of one of the buildings, and the construction of industrial warehouses within and near the factory site have introduced “elements of degradation that also negatively affect potential future social planning, testifying to the rupture of that relationship between buildings and the broader territorial (physical and social) context that was the focus of Olivettian attention and action43”. Even the most recent functionalization projects – though doomed to fail - seem to ignore this relationship (fig. 7)44.

Paradoxically, crucial in this process is the UNESCO listing of “Ivrea, industrial city of the 20th century” in 2018.45 The attractive force of the UNESCO nomination has positively affected the urban sphere, putting the city of Ivrea at the centre as the exclusive protagonist. While this prestigious recognition has fostered the process of community awareness of Olivetti architectures in Ivrea46, at the same time, the process of marginalisation of the other realities that arose under the influence of the enterprise in Canavese has been exacerbated.

The Scarmagno industrial hub was conceived under Olivetti’s auspice but was born and grew out of it as a plant without its community. Despite its architectural space qualities, the integrated production-territory-community system fails, with it also the identity recognition and belonging that increases the territory value47. The dynamics of this process once again confirm the community’s archaic, lost, or unreachable nature. The central role given to Olivetti’s utopia resides in the need to give back to the men’s opera their lost harmony, which Western culture has always looked at with regret48.

On the other hand, the main critical node of the Olivetti model is its perpetual inactuality49. In the 50s, the concentration of many activities integrated in the political system and governance of the territory – may be suitable for nowadays – was not fully accepted. At the same time, today, these experiences are seen through the lens of nostalgia, pride, and distrust (fig. 8).

At least since the 1980s, cultural and political dynamics diverged – if not openly contrasted – from Olivetti’s corporate model based on a very deep link between cities and territory, leading to the Olivettian memory’s oblivion.

Alongside academic debate, a recent focus on this criticism has been pointed out by the research held by the Turin Superintendence of architectural and landscape heritage (SABAP-TO), and by the Ministry of Culture (MiBACT) in cooperation with Regione Piemonte50. In 2020, the new landscape plan for the region has focused specifically on Canavese territory by pointing out the difficulties of managing the protection and enhancement of an essentially forgotten heritage and an area on which governance that integrates local authorities, the region and productive realities does not yet insist.

At least at the beginning of Olivetti’s history, community and region projects coincided, and embodied a multi-sectoral district microcosm. Questioning the outcomes of this experience means investigating the roots of the contemporary debate on the so-called ‘smart cities, smart lands, smart communities or urban bioregions’51.

The failure of Adriano’s ‘regional city’ seems to have entailed the collective feeling of a rejection of Olivetti’s industrial legacy. On the other side, it becomes a perfect hypostasis of Becattini’s “spring charged over the centuries”52, whose torque derives from that mixture of territory, society, production, politics and culture that Olivetti’s Community was intended to be. Reached its maximum in the 1950s, the spring’s ‘twist’ loosened from the 1960s onward, not only because of the deep corporate crisis that followed Adriano’s death but also, inevitably, as a result of the chthonic changes of the entire Western society that led to May 1968.

In the final instance, the failure of the most recent rehabilitation initiatives in the Scarmagno area contributes to implementing the constellation of architectures that arose in Olivetti’s orbit and were soon forgotten, constituting the most concrete symbol of the myth’s fall.

notes

A special thanks goes to our supervisors, proff. Elena Dellapiana and Maddalena Scimemi, and to the Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti’s staff, in particolar to Lucia Alberton, Enrico Bandiera, Antonio Perazzo, Marcella Turchetti, and Anna Maria Viotto for their availability and support.

Magnaghi, Alberto. 2019. "Ripartire dal territorio. Dalla comunità concreta alle bioregioni." Engramma, no. 166: 131-141. Translation by the authors.

Gemelli, Giuliana. 2000. "Scienze sociali, ingegneria e management. Il ruolo del Servizio di ricerche sociologiche e studi sull’organizzazione nell’innovazione strategica della società Olivetti (1955-1975)". In Nehs/Nessi. Istituzioni, mappe cognitive e culture del progetto tra ingegneria e scienze umane, edited by Giuliana Gemelli and Flaminio Squazzoni, 38-46. Bologna: Baskerville.

Valeriani, Enrico. 1988. Gli architetti di Adriano Olivetti. In La comunità concreta: progetto e immagine. Il pensiero e le iniziative di Adriano Olivetti nella formazione della cultura urbanistica ed architettonica italiana, edited by Marcello Fabbri, Antonella Greco, 117-120. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità. Translation by the authors.

Limana, Francesca. ed. 2015. Adriano Olivetti. L’impresa, la comunità e il territorio, atti del seminario (Roma, Parlamentino del Ministero dello sviluppo economico, 21 novembre 2014), collana Intangibili, no 27. Roma: Fondazione Adriano Olivetti. Bellagamba, Piergiorgio. 1988. "Urbanistica e governo locale". In La comunità concreta: progetto e immagine. Il pensiero e le iniziative di Adriano Olivetti nella formazione della cultura urbanistica ed architettonica italiana, edited by Marcello Fabbri, Antonella Greco, 109-116. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità. Giarrizzo, Giuseppe. 1988. Modernità e “virtù”: il tema della comunità locale. In La comunità concreta: progetto e immagine. Il pensiero e le iniziative di Adriano Olivetti nella formazione della cultura urbanistica ed architettonica italiana, edited by Marcello Fabbri, Antonella Greco, 54-65. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità.

Olivetti, Adriano. 1954. “Perché si pianifica”. Comunità, no. 27. Translation by the authors.

See Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The image of the city, Cambridge (Mass.): MIT press Joint Centre for Urban Studies.

Astengo, Giovanni. 1988. "La rivista “Urbanistica”". In La comunità concreta: progetto e immagine. Il pensiero e le iniziative di Adriano Olivetti nella formazione della cultura urbanistica ed architettonica italiana, edited by Marcello Fabbri, Antonella Greco, 180-192. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità. Translation by the authors. See also: Olivetti, Adriano. 2004. Stato federale delle comunità: la riforma politica e sociale negli scritti inediti, 1942-1945, edited by Davide Cadeddu. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Weil, Simone. 1990. La prima radice. Milano: SE. See also Fiorentino, Caterina Cristina. 2014. Millesimo di millimetro. I segni del codice visivo Olivetti (1908-1978). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Olmo, Carlo. 2001. "Un’urbanistica civile, una società conflittuale". In Costruire la città dell’uomo. Adriano Olivetti e l’urbanistica, edited by Carlo Olmo, 3-21. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità. More detailed information about Valle d’Aosta Master plan: Olivetti, Adriano. 1943. "Prefazione". In Studi e proposte preliminari per il Piano Regolatore della Valle d'Aosta. Ivrea: Nuove Edizioni Ivrea. See also Olivetti, Adriano. ed. 2001. Studi e proposte preliminari per il piano regolatore della Valle d'Aosta, Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità.

Renacco, Nello, ed. 1956. Il Piano regolatore generale di Ivrea, Ivrea: s.n. Scrivano, Paolo. 2001. La comunità e la sua difficile realizzazione. Adriano Olivetti e l'urbanistica a Ivrea e nel Canavese, edited by Carlo Olmo, 83-112. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità. Tafuri, Manfredo. 1964. Ludovico Quaroni e lo sviluppo dell'architettura moderna in Italia. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità.

A very important witness of Olivetti approach to production, territory, and Communitiy is the 1957 film Una fabbrica e il suo ambiente, coordinated by Olivetti’s Direzione pubblicità e stampa (production Meridiana Cinematografica, Script and screenplay by Libero Bigiaretti and Michele Gandin; photography by Giulio Giannini; music by Mario Nascimbene; director Alfredo Bini; directed by Michele Gandin). Ivrea, Associazione Archivio Storico Olivetti (from now on AASO), Collezioni Olivetti, Cineteca Olivetti, Filmati in pellicola, Filmati Olivetti, Film d' Arte e video industriali, Fasc. 59, 1957. [V-A-O-1–7, 59].

Vittoria, Eduardo. 1988. "Adriano Olivetti e la cultura del progetto". In La comunità concreta: progetto e immagine. Il pensiero e le iniziative di Adriano Olivetti nella formazione della cultura urbanistica ed architettonica italiana, edited by Marcello Fabbri, Antonella Greco, 160-164. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità. Translation by the authors.

Lazzarini, Luca. 2018. "Emilio A. Tarpino e i progetti dell’ufficio Consulenza Case Dipendenti Olivetti: un programma tra architettura e costruzione del paesaggio". In Le case Olivetti a Ivrea: l'Ufficio consulenza case dipendenti ed Emilio A. Tarpino, a cura di Carlo Olmo, Paolo Bonifazio, Luca Lazzarini, 119-160. Bologna: Il Mulino. Marson, Anna. 2019. "Breve riflessione sul rapporto tra Adriano Olivetti e il territorio eporediese". In Olivetti. Comunità, conflitti, intelligenze, forme di vita, a cura di Sara Agnoletto, Olivia Sara Carli, Roberto Masiero. Engramma, no. 166: 143-147.

Olivetti, Roberto. 1961. "La società Olivetti nel Canavese. Esperienze di un insediamento industriale in comprensorio agricolo". Urbanistica, no. 33: 64-86.

Silmo, Giuseppe. 2022. Adriano Olivetti e il territorio. Dai centri comunitari all'I-RUR. Plug_in. For a deep description of Adriano’s political and economic approach see Berta, Giuseppe. 1980. Le idee al potere. Milano/Roma: Edizioni di Comunità; and Limana, Francesca, ed. 2015. Op. cit.

AASO, Società Olivetti, Documentazione stabilimenti e immobili Olivetti, Fasc. 1, [Giovanni Astengo] Nuovo stabilimento I.C.O. a Scarmagno. Indagine urbanistica e progetto di sistemazione territoriale. [131152, I-2-55-12, 1].

Ciucci, Giorgio. 1976. "Ivrea ou la communauté des clercs". L'Architecture d'Aujourd'Hui, no. 188. Zorzi, Renzo. 1977. "Ragioni aziendali e sviluppo civile del territorio". Casabella, no. 422: 50-51. Fava, Sabrina. 2020. "Adriano olivetti’s notion of “community”: Transforming the factory and Urban physical space into educational spaces". Ricerche di pedagogia e didattica, vol.15, no. 1: 203-216.

de Witt, Giovanni. 2005. Le fabbriche ed il mondo: l'Olivetti industriale nella competizione globale (1950-90). Milano: FrancoAngeli.

Todisco, Augusto. 1984. "Il Movimento Comunità nel Canavese: prima e dopo". In Fabbrica, comunità, democrazia, edited by Francesca Giuntella, Angela Zucconi, 116-124. Roma: Fondazione Adriano Olivetti.

Mumford, Lewis. 1957. "La nascita della città regionale", Comunità, no. 55. Translation by the authors. Olivetti was strongly influenced by Mumford’s urbanistic theories and studies, formerly translated in Italian by the Olivetti publishing house Edizioni di Comunità: La cultura delle città in 1954 (or. The Culture of Cities, 1938), and Le trasformazioni dell’uomo in 1968 (or. The Transformation of Man, 1956).

Mazzoleni, Chiara, Morreale, Nino, and Ferdinando Scianna. ed. 2006. Carlo Doglio. Il piano della vita: scritti di urbanistica e cittadinanza. Roma: Lo straniero.

Many studies have been carried out about Scarmagno architectural transformation. Among the others: Grignolo, Roberta. 2012. "La sauvegarde du patrimoine industriel récent. De l’étude monographique de l’oeuvre à la mise au point d’un cahier des charges". In Zeitschrift für Schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte/Revue suisse d’Art et d’Archéologie/Rivista svizzera d’Arte e d’Archeologia/Journal of Swiss Archaeology and Art History 69, no. 1: 53- 70. Graf, Franz, and Francesca Albani. 2020. "Zanuso versus Mangiarotti: due interpreti del dopoguerra milanese". In Marco Zanuso. Architettura e design, edited by Luciano Crespi, Letizia Tedeschi, Annalisa Viati Navone. Roma: Officina Libraria: 149; and the recent Quadrato, Vito. 2022. La costruzione della campata in cemento armato per l'industria: il pensiero artigianale di Aldo Favini e Marco Zanuso. Bari: Edizioni di Pagina. 67-73.

Boltri, Daniele, Maggia, Giovanni, Papa, Enrico, and Pier Paride Vidari. 1998. Architetture olivettiane a Ivrea: i luoghi del lavoro e i servizi socio-assistenziali di fabbrica. Roma: Gangemi Editore. Galardi, Alberto. 2001. Alberto Galardi: architetto. Buenos Aires: Fundación Gordon. 82-91.

Astarita, Rossano. 2000. Gli architetti di Olivetti: una storia di committenza industriale. Milano: Franco Angeli.

Bertolini, Clara, and Tania Marzi. 2013. Lo stabilimento Olivetti di Scarmagno: la sperimentazione tecnologico-strutturale delle reticolari spaziali in acciaio. Le Giornate Italiane della Costruzione in Acciaio. The Italian Steel Days (Proceeding), La Stamperia Digitale srl: Napoli, 973-980.

See the Ottavio Cascio’s undated drawings held in AASO, Società Olivetti, Fondo Ottavio Cascio, Fasc. 544.1, Scarmagno 1964. Progetto indicativo nuovo stabilimento. Arch. Cascio, [1964]. [D-D-2-3, 32, 544.1].

Astengo, Giovanni. 1962. "Scarmagno, un nuovo complesso industriale". Notizie Olivetti, no. 76: 57-68; Vittoria, Eduardo, Zanuso, Marco. 1962. "Paesaggio, architettura, design". Notizie Olivetti, no. 76. The role of the dissemination of culture through publishing in Olivetti has been recently studied in Accornero, Cristina. 2021. L'azienda Olivetti e la cultura: tra responsabilità e creativa (1919-1992), Roma: Donzelli.

Morreale, Giampietro. 2019. "Mediobanca e il salvataggio Olivetti, Verbali delle riunioni e documenti di lavoro 1964-1966, Filago: Pozzoni; Silmo, Giuseppe. 2022. Olivetti. La crisi del 1964 e la perdita progressiva dei suoi valori fondativi". Olivettiana.it. Published on-line. Accesed April 11, 2023. https://olivettiana.it/olivetti-la-crisi-del-1964-e-la-perdita-progressiva-dei-suoi-valori-fondativi/.

The location of these industrial poles was respectively determined by the acquisition of Serio, a historic typewriter company in Crema taken over by Olivetti in 1963; while the choice of Marcianise is conveyed by the possibility of taking advantage of funds from the Cassa del Mezzogiorno, funds linked to the reconstruction plan co-financed by U.S. funds. The role of Olivetti in the development of Southern Italy has been studied in Castanò, Francesca. 2020. "Il sicuro procedere dell’industria lungo la via del sud. Il caso Olivetti di Marcianise". Storia Urbana, no. 165: 83-103. Castanò, Francesca. 2023. "The construction of the modern factory. The introduction of prefabrication in Terra di Lavoro". VITRUVIO - International Journal of Architectural Technology and Sustainability, vol. 8, no. 2: 18-33. Tosone, Alessandra, Di Donato, Danilo. 2021. "Industrialization by CasMez and steel built factories in Southern Italy". In History of Construction Cultures, Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Construction History (Lisbon, Portugal, 12–16 July 2021). Boca Raton/London-New York-Leiden: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Group. vol. I, 602-609.

AASO, Società Olivetti, Documentazione stabilimenti e immobili Olivetti, Fasc. 1, [Roberto Guiducci, Tekne] Urbanizzazione del comprensorio Olivetti di Scarmagno. [I-2-55-12, 1].

IRES. 1963. Piano di Sviluppo del Piemonte. Studi e documenti. “Quaderno n. 1”, Torino.

The working process of UMI’s has been described in the Olivettian docu-film Minifabbriche: Le Unità di Montaggio Integrate Olivetti in 1975 (AASO, Collezioni Olivetti, Cineteca Olivetti, Filmati in pellicola, Filmati Olivetti, Film d'Arte e video industriali, Fasc. 105. Music: Bosio Piergiorgio; Photography: Bosio Aristide, Damicelli Mario). See also Butera, Federico, and Giovanni De Witt. 2011. Valorizzare il lavoro per rilanciare l'impresa. La storia delle isole di produzione alla Olivetti negli anni '70. Bologna: il Mulino.

Migliasso collaborated formerly as an internal technician and later through Sertec, an engineering society he founded in 1968.

Assennato, Marco. 2019. "Olivetti, un inattuale costruttore di miti". Engramma, no. 166: 51-55, in part. 52. Translation by the authors.

See Centro Ricerca Alfredo Galmozzi (editor). 2003. Dall'Everest all'Olivetti, Crema: CRAG.

Cesari, Pietro. 2016. "Introduzione". In Architettura per un’idea. Mattei e Olivetti, tra welfare aziendale e innovazione sociale, edited by Cesari Pietro. Bologna: Il Mulino, 9-22, in part. 15. Translation by the authors.

The ex-Olivetti factory hosts the Informatics department of the University of Milan since 1995 thanks to a master agreement with Regione Lombardia. Ernesto Damiani, Nello Scarabottolo, Dal mangiaspago alla connection machine: appunti per una storia breve dell’informatica all’Università di Milano, s.d., edited on-line. Accessed August 17, 2023. https://www.aicanet.it/documents/10776/3178360/MILANO+STATALE.pdf/.

For Crema see Bacchetta, Simone. 2023. "La rinascita dell'ex Olivetti tra passato e futuro". Crema oggi. Published on-line. Accesed July 13, 2023. https://youtu.be/uTMY71rLaig. For the case of Marcianise see Red. 2020. "Ex Olivetti nell'abbandono, Pignetti: "Va restituita alla collettività"". Caserta News. Published on-line. Accesed July 31, 2023. https://www.casertanews.it/attualita/ex-olivetti-abbandono-pignetti-collettivita-marcianise.html; the events promoted by Materia Viva association, such as Settembre Olivettiano in 2022 (https://www.casadelcontemporaneo.it/materia-viva/) or the recent Un calcolo fallito: la fine della grande Olivetti di Marcianise, 2023, published on-line. Accesed August 20, 2023. https://derivesuburbane.it/archeologia-industriale/stabilimenti-industriali/ex-olivetti-di-marcianise/. A special thanks to Marcella Turchetti who informed us about this and the following oral history documents.

Silmo, Giuseppe. 2022. Op. cit.,167-168.

This aspect is show in some of these activities’ websites, where the auroral role of Olivetti is pointed out, e.g. La storia della cantina. Edited on-line by Cantina della Serra. Accessed August 3, 2023. https://www.cantinadellaserra.com/la-cantina/.

Sapelli, Giulio. 2005. "Postfazione. Lo “scandalo” della memoria olivettiana". In Uomini e lavoro all’Olivetti, edited by Novara, Francesco, Rozzi, Renato, Garruccio, Roberta. Milano: Mondadori. 607-614. See the recent complaint report Sono scappati tutti quanti da una catastrofe! - troviamo un call center nella Olivetti abbandonata!, realised by Riccardo Dose in 2023 (published on-line. Accessed August 20, 2023 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IgxjXN5GaHk).

Turin, Archivio ISMEL - Istituto per la Memoria e la Cultura del Lavoro, dell'Impresa e dei Diritti Sociali. Multimedia resource edited by Capella Giuseppe, Sciandra Ezio and Benedetto Massimo. 2019. Olivetti | La storia sindacale e la trasformazione delle tecnologie. Documento Si poteva salvare la Olivetti?, proceedings of the symposium FIOM CGIL (Ivrea, 13 December 2008), 2008.

Progetto di sperimentazione per l’attuazione del piano paesaggistico regionale Ambito Eporediese Rapporto Finale - Settembre 2020, edited by Regione Piemonte, SABAP-TO, MIBACT. e-book, 2020: 95. Published on-line. Accessed June 20, 2023. http://sabap-to.beniculturali.it/Eventi/SABAP-TO%20Ricerca%20Progetto%20Piano%20Paesaggistico%20Regionale.pdf. Translation by the authors.

Garda, Emila, Di Mari, Giuliana, and Caterina Franchini. 2022. "Scarmagno: da area industriale dismessa ad area industriale in divenire / Scarmagno: from disused industrial area to becoming industrial area". In Stati generali del patrimonio industriale 2022. Venezia: Marsilio. 2144-2154. Ronchetti Sandro. 2022. "Scarmagno, un’altra occasione all’ex Olivetti: un nuovo polo logistico". La Sentinella del Canavese. Published on-line. Accessed August 1, 2023. https://lasentinella.gelocal.it/ivrea/cronaca/2022/07/21/news/scarmagno-un-altra-occasione-all-ex-olivetti-un-nuovo-polo-logistico; Burbatti, Federica. 2023. Il sogno al palo. L'ex Olivetti di Scarmagno eterna addormentata. RAI report. Published on-line. Accessed September 14, 2023 https://www.rainews.it/tgr/piemonte/video/2023/06/scarmagno-ex-olivetti-il-sogno-al-palo.html; Gibello, Luca. 2023. "Scarmagno: la fabbrica di Olivetti e i capannoni-scatoloni". Il giornale dell’Architettura. Published on-line. Accessed July 30, 2023 https://ilgiornaledellarchitettura.com/2023/03/22/scarmagno-la-fabbrica-di-olivetti-e-i-capannoni-scatoloni/.

Bonifazio, Patrizia, and Paolo Scrivano. 2001. Olivetti costruisce: architettura moderna a Ivrea: guida al museo a cielo aperto. Milano: Skira; Bonifazio, Patrizia, Giacopelli, Enrico. 2007. Il paesaggio futuro. Letture e norme per il patrimonio dell’architettura moderna di Ivrea. Torino: Allemandi; Fasana, Sara, and Enrico Giacopelli. 2022. "Strumenti integrati per la manutenzione e il recupero delle architetture Olivettiane a Ivrea". In Stati generali del patrimonio industriale 2022. Venezia: Marsilio. 1542-1555.

Della Puppa, Federico. 2019. "Dal valore economico al valore sociale". Engramma, no. 166: 111-116, 115.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. 1986. La communauté désœuvrée. Paris: Bourgois (trad. it. edited by Moscati, Antonella. 1992. La comunità inoperosa. Napoli: Cronopio); Biraghi, Marco. 2019. "Comunità". Engramma, no. 166: 56-62, 58 sg; A Assennato, Marco. 2019. Op. cit., 51-55.

That is the «attualità dell’inattuale» described by Aldo Bonomi (2019. "Fare comunità nei tempi della simultaneità". Engramma, no. 166: 67-77).

Progetto di sperimentazione…, cit.

Bonomi, Aldo, and Roberto Masiero. 2014. Dalla smart city alla smart land. Marsilio: Venezia; Magnaghi, Alberto. 2014, La regola e il progetto: un approccio bioregionalista alla pianificazione territoriale. Firenze: University Press.

Becattini, Giacomo. 2015. La coscienza dei luoghi. Il territorio come soggetto corale. Roma: Donzelli. 95.

Jiayao Jiang Pedro Marroquim Senna

Kalinka Janowski

Maryia Rusak

Azize Elif Yabacı