City walls and highways are key infrastructures present in historic cities. For different reasons, both have been considered either a limitation or an engine for urban development. This article will shed light on two cases within different cultural contexts, in China and Brazil, investigating the conceptual correlation between destruction, cultural heritage and public participation.

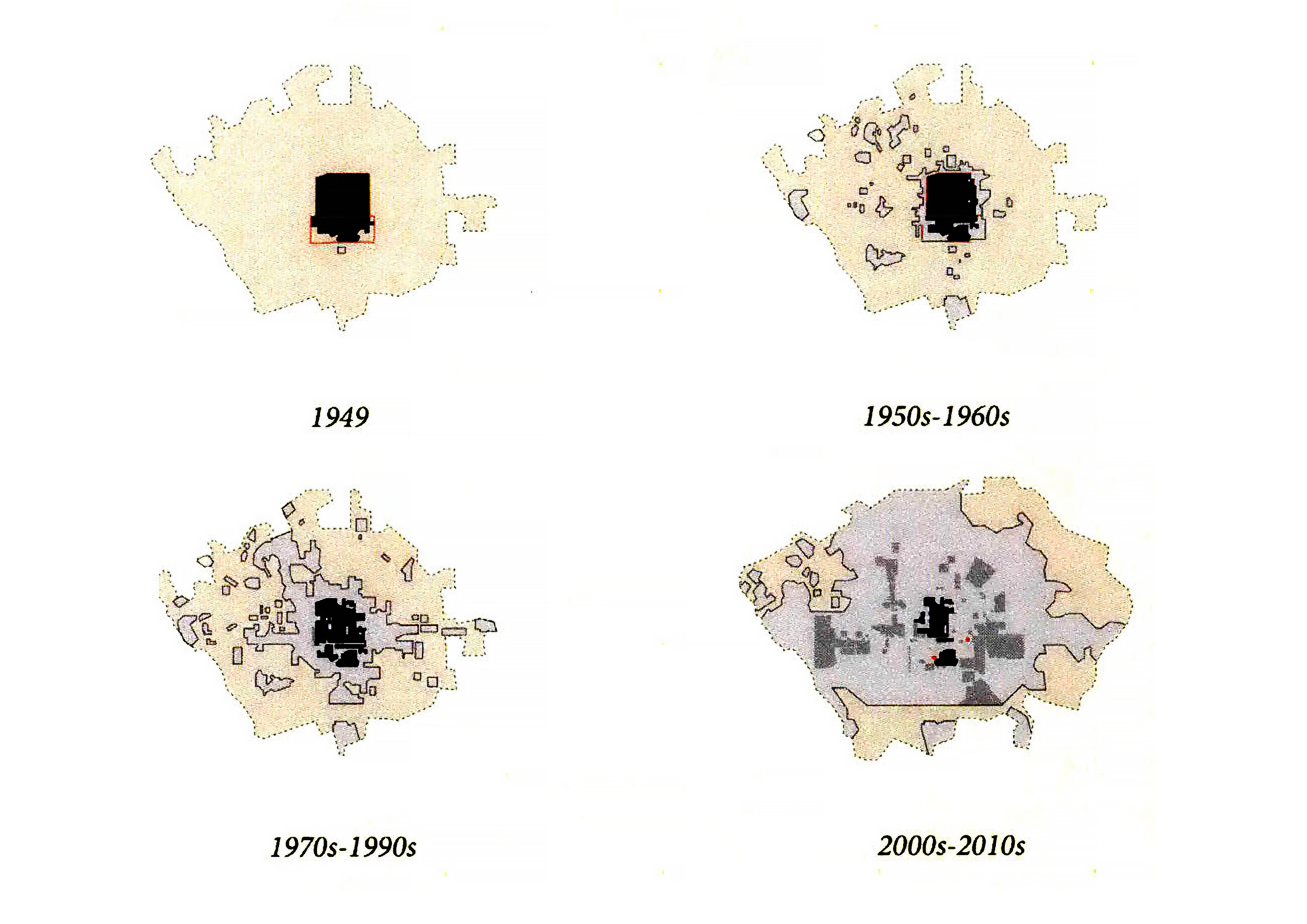

Built during the Ming Dynasty, Beijing’s City Walls remained largely intact for centuries as a symbol of centralised power. Between the 1950s and the 1960s, a period of fast urban development under a new governance, the values attributed to such structures were deemed incompatible with the idea of national identity, and then, large sections of the walls were demolished to prioritise the construction of new infrastructure. Previously guided by controversial ideals of modernization, nowadays the government is planning to reconstruct specific sections of the walls as a strategy to recover what in China is known as ‘cultural confidence’. Such decisions express the way heritage values are politically managed for the legitimisation of a cultural heritage narrative.

There are circumstances in which official narratives can be redefined by social engagement. The construction of the “Mihocão”, a 3.4 km elevated highway inaugurated in 1971 in the city of São Paulo, constituted a wound in the historic urban fabric, which interrupted preexisting social dynamics and triggered material decay. After decades, the necessity for coexistence of the local community and the imposed infrastructure conditioned the population to attribute new values to the highway, transforming it into a linear park for local cultural expressions. Such a resilient attitude towards the highway as a historicized element led to nondestructive policies for urban regeneration and the creation of new intangible heritage.

Through a thoughtful analysis, this article aims to highlight that the notion of identity is in constant change. Despite the strength of official directives, people have the ability to attribute new values over the destruction of old ones, creating new narratives which better represent their civic will. Since transformation is inherent to historic cities, it is fundamental for the civic society to be heard in the decision-making process towards a more resilient and sustainable urban development.

Defensive complexes and primary roads are very persistent structures in a territory, strongly configuring the urban morphology of old settlements and dictating the rules for their expansion through time. The substantial scale of such urban linear structures possesses the potential to serve as catalysts or constraints in urban development and transformation processes.

In order to comprehend the connection between the concepts of destruction, cultural heritage and the role of the public participation in both destructive and regenerative actions in the city, this article sheds light on two cases within different cultural contexts, the Beijing City Walls, in China, and the elevated highway known as the “Minhocão” in São Paulo, Brazil. Although built in different periods and with divergent motivations, both urban structures share similarities regarding their contemporary impact on local collective memory and on the generation of new cultural heritage, while consistently contemplating destructive actions. Moreover, since both case studies are still currently part of ongoing social processes within their own cultural contexts, the theoretical references mentioned in the present paper could not overlook newspaper chronicles and social media publications, for those are manifestations mostly contemporary to the events and essentially related to how different groups behave towards their cultural heritage in different time lapses. Such references are carefully and constantly sowed to the elaboration of the local legal frameworks.

A brief history of Beijing City Walls

As said by the Swedish scholar Osvald Sirén, “The city walls, indeed, constitute the most fundamental, impressive, and enduring aspect of Chinese cities”1.The city walls not only physically delineate urban spaces but also contribute significantly to the ideology of hierarchy within the urban landscape2. For instance, the concentric urban layout with the Imperial Palace at the centre illustrates the concept of "mandate of heaven", the emperor’s divine entitlement to govern. Serving as imposing barriers, the city walls delineated distinct social strata and fortified the hierarchical fabric of society, amplifying the sovereign’s singular and exalted status.

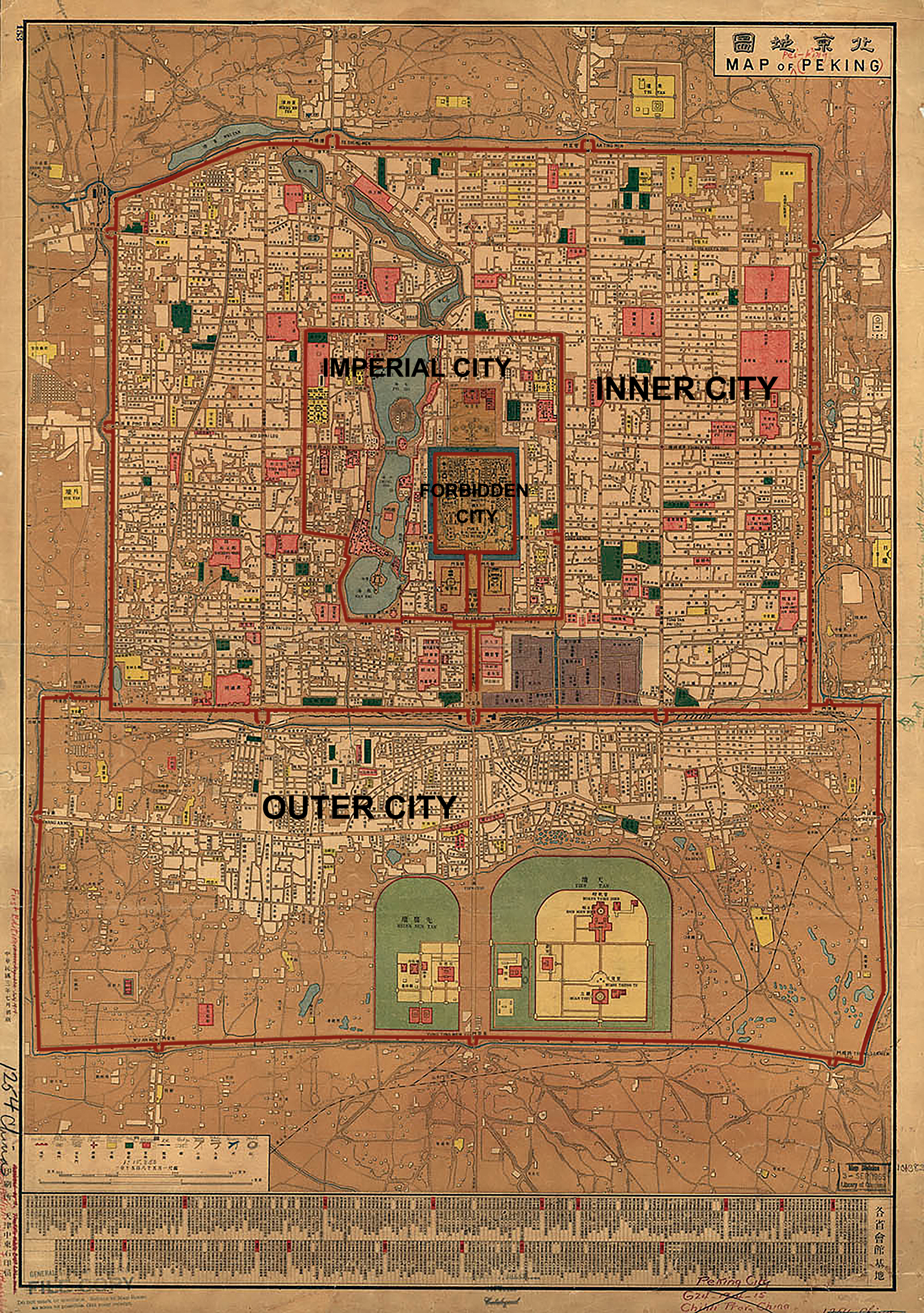

Beijing, as the eminent capital of China for five dynasties, boasted a formidable City Wall, also referred to as the Beijing City Fortifications. This monumental defensive edifice enveloped the ancient city of Beijing, undergoing multiple transformations throughout the expanse of seven centuries. The city walls were initially established during the Yuan Dynasty and completed in the Ming Dynasty, which continued being in use until the Republic of China era. The urban layout of four concentric walls in Beijing was still well-preserved in the early years of the Republic of China. From the core to the periphery, they consisted of the Forbidden City (Zi Jin Cheng 紫禁城), the Imperial City (Huang Cheng 皇城), the Inner City (Nei Cheng 内城) and the Outer City (Wai Cheng 外城), which in total were more than twenty kilometres long (fig.1)3 . Embellishing these walls there were over thirty grand gates and ornate corner towers, representing an important part of the city’s history and cultural heritage.

The public participation in the destruction process

In the early 20th century, China experienced a profound shift in its political system, which marked the end of millennia-long imperial rule. In 1912, with the establishment of the Republic of China, after a struggle between the northern and southern factions, Beijing ultimately retained its position as the national capital. Yuan Shikai later issued a presidential decree approving the establishment of the Beijing Municipal Office in April 1914, appointing Zhu Qiqian to supervise municipal affairs in Beijing4. At the time, the vast majority of the citizens still resided within the old city walls, and people entering and exiting the city of Beijing had to pass through three layers of “checkpoints”: city gates and gate towers, the moat outside the city walls, and the modern-built circular railway that encircled the city. The change of political system and new way of life instilled an eagerness to modernise the capital city, leading to a significant reinterpretation of the Beijing City Walls. The city walls were mostly perceived as a physical impediment to urban development, a hindrance to modern transportation, or a negative symbol of lingering imperial control.

With proactive measures, the Beijing Municipal Government completed several major projects between 1914 and 1924, including the partial demolition of the Zhengyang Gate (正阳门)5 of the city walls, the renovation of Front Gate (前门), and the construction of the Circular Railway along the walls. Numerous openings in the imperial walls were created, gateways were added, and new roads were constructed to improve traffic flow in the city6. In addition, there were spontaneous movements driven by citizens to dismantle their city walls. By analyzing contemporary chronicles in Beijing's newspapers, it became evident there was a prevailing sentiment among citizens who celebrated the dismantling of the city walls to open the way for a new road infrastructure7. For instance, it was certain members of the populace who initially proposed the opening of the Gate of Peace (Heping Gate 和平门) within the city wall. In 1921, a civic organization advocated for “demolishing the fossilized bridge and opening a hole in the city wall”8. This initiative intended to connect the south Xinhua Street and the north Xinhua Street as a symbolic link to China’s political division between north and south at that time, advocating for hope towards peace and unification. In this way, the connection between politics, new urban transportation, modern development, and the demolition of the ancient city walls had been executed9.

Furthermore, beyond political and utilitarian considerations, a shared interest in the bricks of the Imperial City Walls emerged among officials and the public, primarily driven by economic motivations. This interest stemmed from the economic gains achievable through the sale of these bricks, and a substantial portion of the Beijing City Walls was methodically disassembled and sold as building material. In 1924, orchestrated by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Municipal Government of Beijing, a large-scale demolition of the Imperial City commenced, with intentions to fully dismantle the north-eastern and western sections of this monumental structure10.

Diverse debates on the fate of the City Walls in the new socialism era

The establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949 infused new vitality into Beijing, setting forth its path towards modernization through extensive development. As a metropolis, the urban spatial structure and layout of Beijing were shaped during the early years of the new China through urban planning efforts. At the outset of urban planning by the Beijing Municipal Committee in 1949, significant disagreements and debates emerged, notably regarding the location of the new administrative agencies. This period saw the emergence of two conflicting approaches: one advocating for an inner-city layout and the other for concentrated construction in the western suburbs, the latter would preserve the old city as a whole including the city walls11.

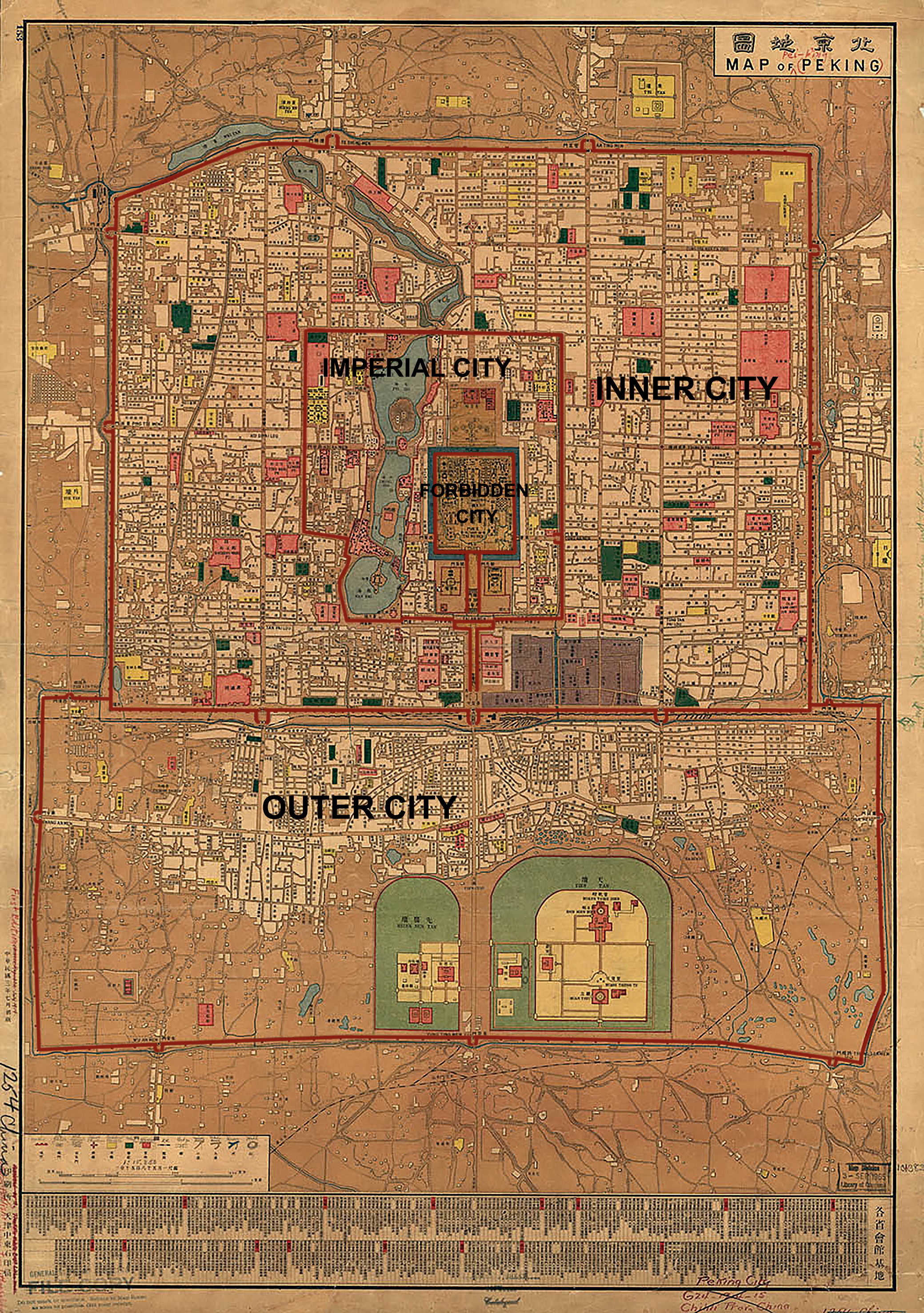

Within the framework of “Suggestions on the Location of the Administrative Center of the Central People's Government” in February 1950, architects Liang Sicheng and Chen Zhanxiang, proposed a planning strategy of division between the old and the new cities, and designed a new administrative centre in the western suburbs. Liang and Chen’s visionary proposal advocated for the transformation of the Beijing City Walls into an extensive linear park for the benefit of the citizens (fig.2):

The current city wall serves as a historical relic and artistic embellishment [...] Atop of the city wall, an exceptional public park could provide a space where people can take walks, seek shade, read books, peruse newspapers, and enjoy the scenery (in line with traditional Chinese customs). Below, city gates could be opened as per transportation needs12.

According to those experts, the city walls were integral facets of Beijing’s cultural heritage, asserting that its obliteration amounted to an irreplaceable forfeiture of the city’s historical narrative and unique identity. As well, they declared that the city walls played an essential role in safeguarding the historic urban fabric, since they acted, to some extent, as a deterrent against uncontrolled urban expansion. In this way, as urban development encroached upon the city’s perimeters, the city walls limited and locally defined the transformation process of the urban fabric (fig. 3).

In contrast, proponents of its removal argued that the city walls, artefacts of yesteryears, had outlived their practical utility, and their elimination was indispensable to facilitate the city’s dynamic growth and contemporary advancement. Such a polarity of perspectives would further underscore the intricate layers that have animated the discourse surrounding that transformative event. After various discussions, the proposals for preserving the Beijing City Walls were rejected and counteractions were implemented, and the decision made for dismantling the city walls is deeply rooted within the socio-political background. At the moment, post-war urban planning in China was heavily influenced by the Soviet Union. A cohort of Soviet specialists made multiple visits to Beijing and proposed several influential guidelines for the urban development of the city as the new capital in this specific political and historical context. In 1953, the Beijing Municipal Committee of the Communist Party of China established a planning working group directly under its leadership, and they also invited Dmitry Dmitrievich Baragin, a Soviet expert employed by the Central Department of Building Construction at the time, to serve as a consultant. After several months of continuous research, they completed the "Draft Plan for the Reconstruction and Expansion of Beijing City'' in early December 1953, which was later submitted to the central authorities. This marks the first comprehensive urban planning in the history of Beijing city planning, holding historical significance. The Soviet experts advocated a shift from “a city for consumption” to “a city for production”, prioritising industrialisation and development over preservation of Beijing. This discourse swiftly evolved into a political battleground, reigniting discussions about the symbolic significance of the City Walls in relation to imperial power. As noted, “The arrangement of concentric city walls surrounding the imperial palace exemplifies the feudal emperor's perception of absolute authority and the desire to maintain feudal rule while defending against potential peasant uprisings13”.

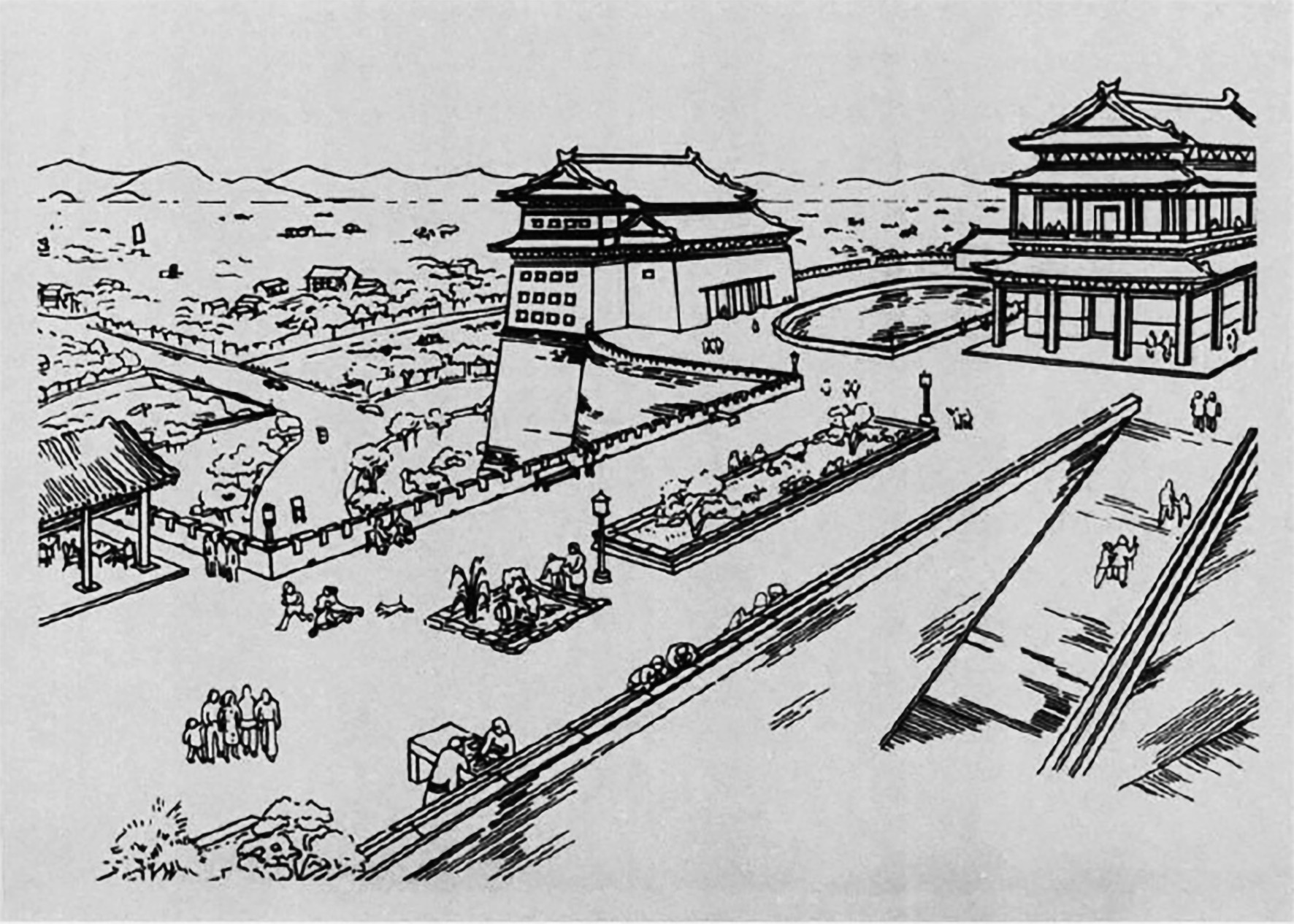

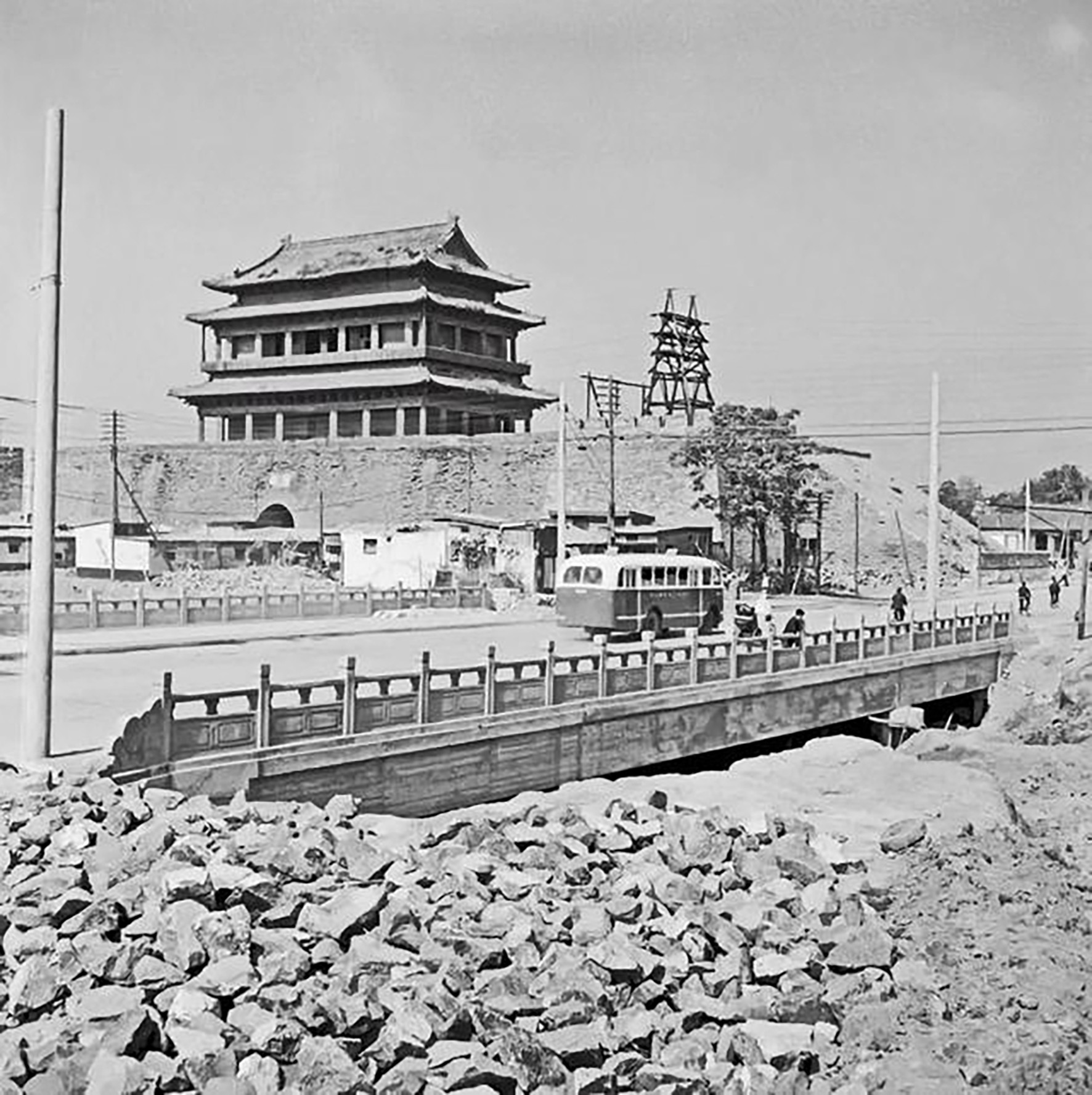

As documented, there were still some preservation projects carried out during 1951 for six city gates and their respective towers14. However, those projects were terminated shortly after and starting from 1952, the outer city wall of Beijing was gradually dismantled through various methods, such as organizing voluntary labour by citizens or mobilizing different units to dismantle the wall and collect bricks and soil. On 12th August 1953, Mao Zedong stated during the National Financial and Economic Work Conference, saying that “The demolition of the city walls is a significant issue that has been decided by the central government and is being implemented by the government15”. Within a few years, the Outer City Walls of Beijing were completely dismantled. In 1969, the Inner City Wall was completely demolished during the construction of the subway and preparations for war and famine (fig.4).

The reconstruction process of Beijing City Walls and the redefinition of cultural identity

Over half a century has passed, and concerted efforts have been made in recent years to restore and preserve the remaining sections of the Beijing City Walls while reconstructing those previously demolished. The phenomenon demonstrates a change of legitimate discourse in China, which is currently promoting “cultural pride” and recovering the national identity through reinterpretation of the historical remains. Consequently, reconstruction serves as a crucial tool for identity building and meaning making.

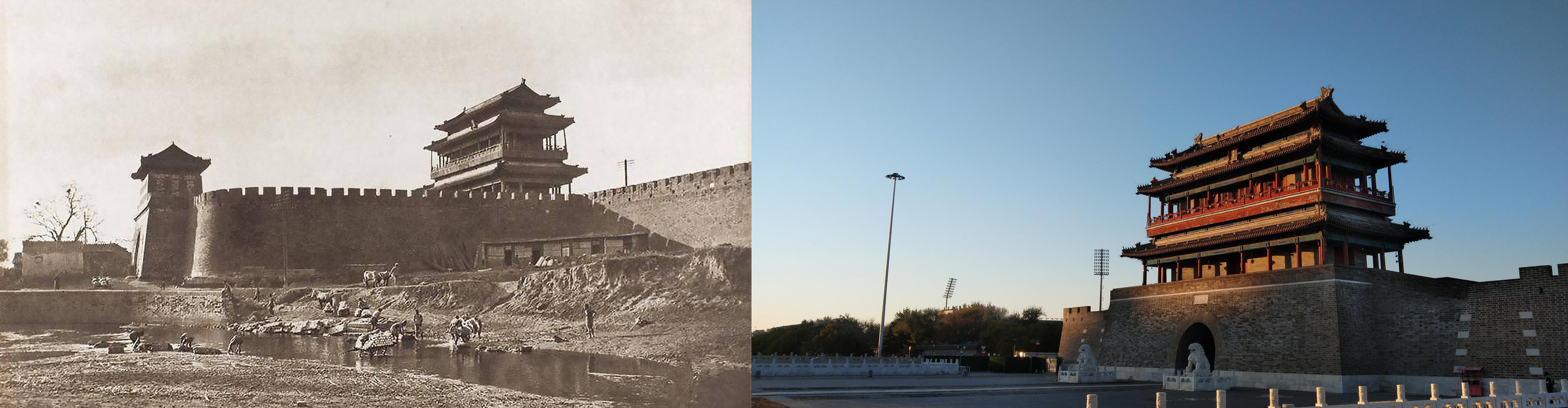

Some sections of the Beijing City Walls which had already completely disappeared were reconstructed for their symbolic meaning. For instance, a proposal for the reconstruction of Yongding Gate (永定门) was brought forward to the Beijing Municipal Government in 2000 (fig. 5). Originating from the Ming dynasty in 1553, Yongding Gate was the principal entrance of Beijing's outer city wall during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Positioned along the central axis of Beijing, it held the distinction of being the largest gate in the outer city wall and served as a crucial thoroughfare in and out of the capital from the south. However, Yongding Gate was entirely dismantled in 1957. The ambitious project to reconstruct Yongding Gate commenced on 14th February 2004, and completed on 18th August 2004, using traditional techniques and partially the original bricks. Nowadays, Yongding Gate is no longer a defensive facility, but it takes on other functions. Many commercial facilities and cultural attractions have been built around Yongding Gate Square, attracting local citizens and international tourists. It is important to point out that these reconstruction activities are within the plan for strengthening Chinese culture’s global impact. As a symbolic site on Beijing's central axis, Yongding Gate will contribute to the application of the “Central Axis of Beijing” as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

In this vein, the fate of these city walls in each era reflects not only the changing political landscape but also the evolving perceptions of cultural heritage and its integration with urban life. The physical presence of these walls served as a tangible representation of power, authority, and social hierarchy in the past, while their destruction or reconstruction in different epochs revealed shifting interpretations of history, culture, and urban heritage.

The outcomes of a destructive process may be incredibly diverse, and differently from Beijing's case, the present study will now explore the concept of destruction through a case in which the construction of an elevated highway in the city centre of São Paulo did not only create urban discontinuity and decay, but also how it was surprisingly transformed by collective endeavour into an important support for the generation of new cultural practices.

The “great worm” of autocracy

After the military coup of 1st April 1964, and the deposition of the President João Goulart (1661-1964), Brazil became a civil-military dictatorship, whose government would last for the following 20 years, until 15th March 1985. It was between the years of 1969 and 1971 - period known as the “Economic Miracle” - that an important elevated highway was conceived in the city of São Paulo as a symbol of industrial and economic progress, as well as a concrete expression of values related to power and autocracy.

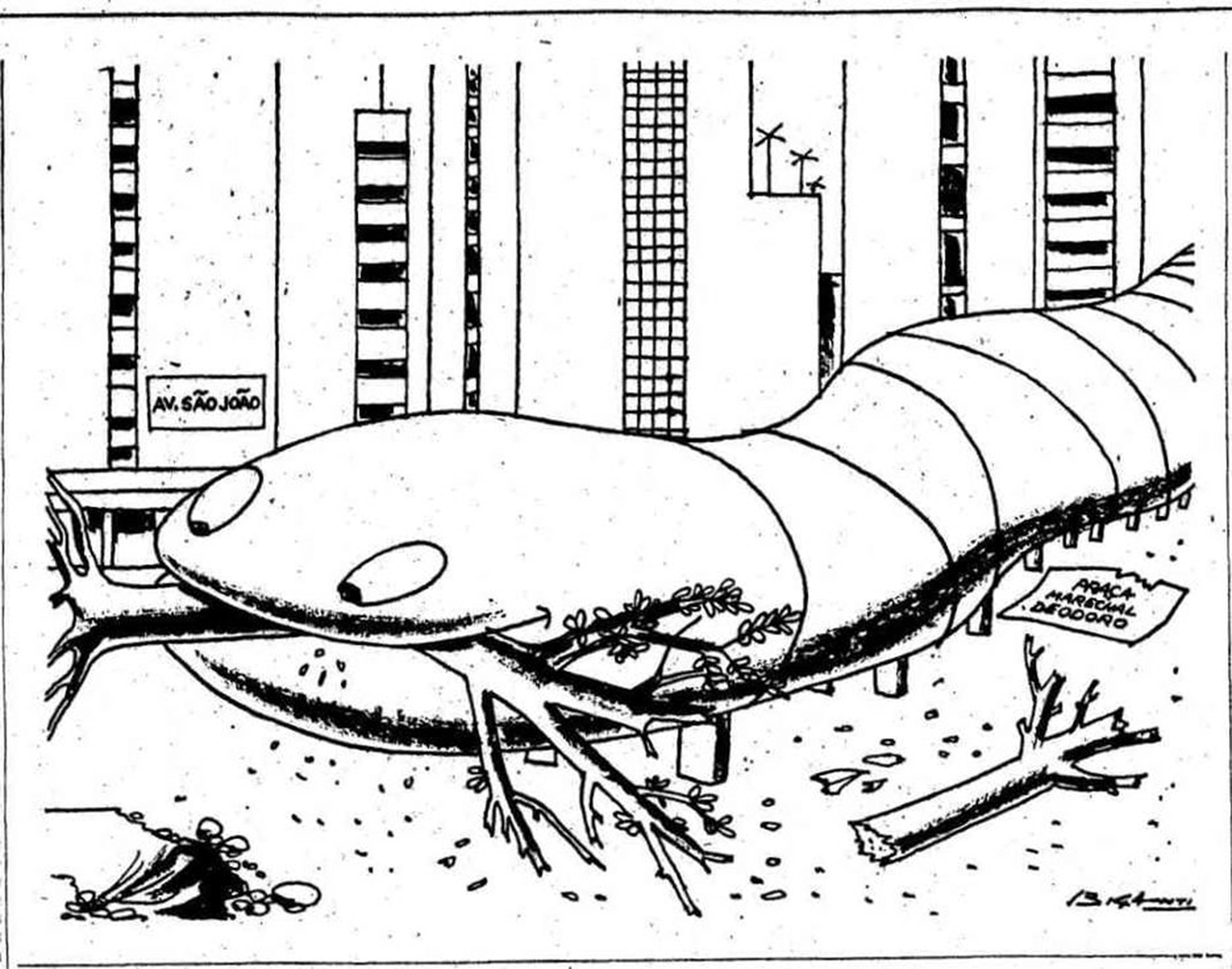

After the coup, strategies founded on the idea that individual means of transportation were the greatest expression of modernity were implemented, which goal was that of “strengthening the administrative and executive image of efficiency portrayed by the military government, elevating technocracy over politics for the construction of a new urban landscape”, with harsh consequences to the architectural heritage and the social life of the city’s core16. The construction of the new highway was made possible by São Paulo’s new mayor Paulo Maluf (1969-1971), who clearly associated the new infrastructure with the regime by naming it after the politician and Army Marshal Artur da Costa e Silva, second dictator president of Brazil from 1967 to 1969. The Elevated Highway President Costa e Silva was soon nicknamed “Minhocão”, the “Great Worm” (fig.6), that slithers for 3.4 km above important historical squares and streets of São Paulo, such as the Marechal Deodoro Square and the symbolic São João avenue, representing a structural rupture between the historical centre of São Paulo and the western wealthier area of the city.

Moreover, it is important to mention that the metro system also constituted important political propaganda for the regime. However, the construction of the metro lines was surrounded by contradictions. In fact, the planned east-west line would follow the exact same route of the elevated highway “Minhocão”, which works had just started. Pointing out the uselessness of the new highway, opposition to its construction was vivid since then, coming from relevant newspapers and from significant politicians, such as José Vicente Faria Lima, military engineer and the previous mayor of São Paulo (1965-1969). As published by the newspaper “O Estado de São Paulo” in December 1970, by prioritising the highway, the government was about to issue a death sentence to both the metro line and part of the historical São João Avenue running below, attitude aligned with the authoritarian posture of the regime. In fact, because of the construction of the “Minhocão”, the inauguration of the metro line, planned for 1971, was delayed by 10 years.

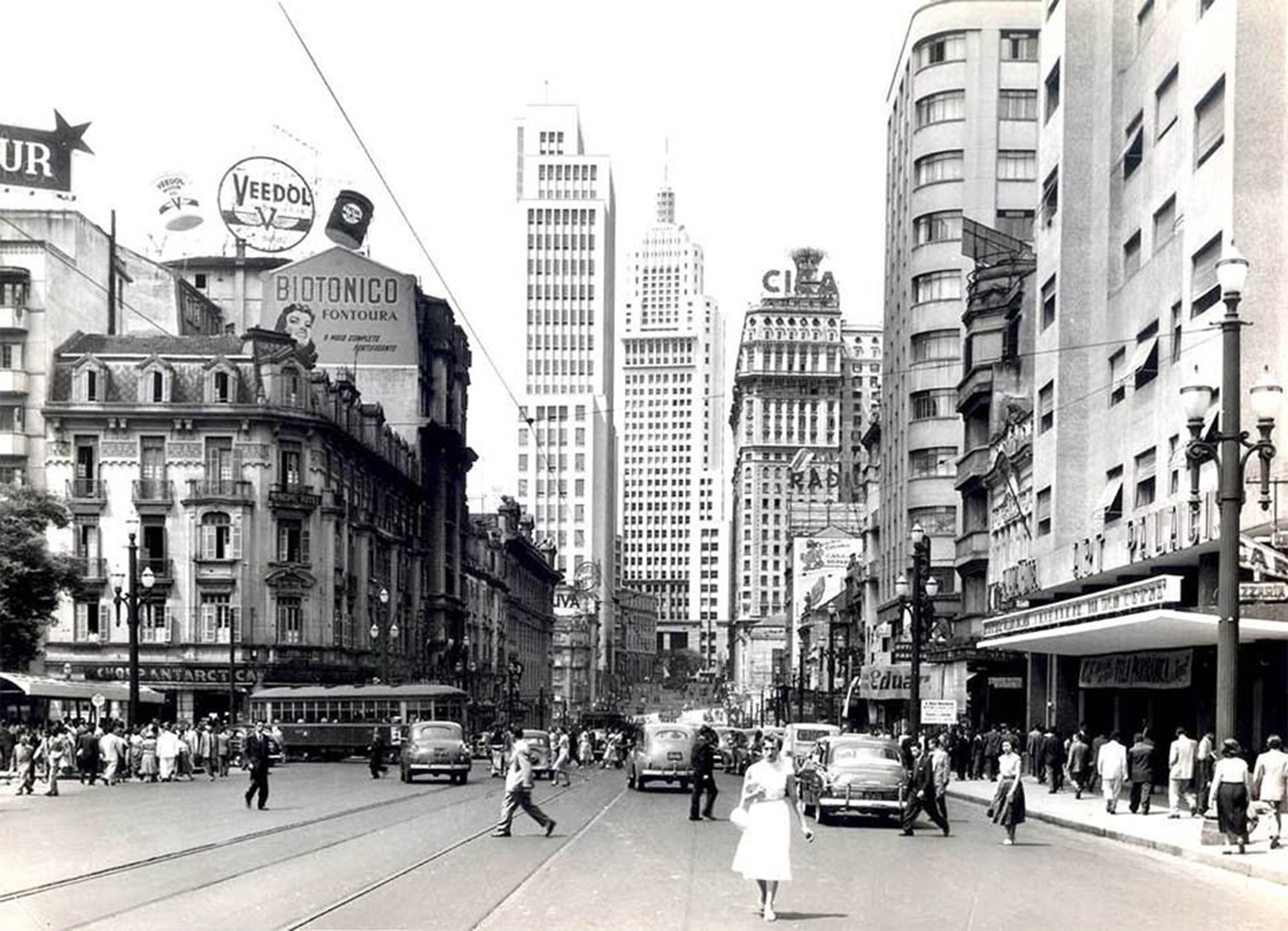

The consequences of autocracy

The construction of the elevated highway caused a deep negative impact in the historical area along its route, such as environmental problems related to noise and pollution; local urban and architecture decay; economic devaluation of real estate; and consequently, the deterioration of preexisting social dynamics with the emptying of the city centre. It is important to highlight that the origins of São João Avenue date back to the 17th century, when it was conceived as a secondary slope to connect the historical hill of São Paulo17 with private properties in the periphery. The simple dirt road acquired importance during the 19th century due to the expansion of the city and, in the first decades of the 20th century it became part of urban improvement plans18 that widened the previous path in 30 metres transforming it into an important bourgeois avenue with residential palaces for the economic elite with new cultural and entertainment facilities, such as parks, caffés, the Municipal Theatre (1911) and movie theatres. Such political interest in the area encouraged the construction of a variety of buildings with eclectic architectural features, combining neoclassical, medieval, renaissance and baroque elements, which would later coexist with skyscrapers in Art Decò style and then modernist buildings (fig. 7).

The diversity that characterizes the urban and architectural heritage of that area suffered a great impact with the inauguration of the “Minhocão” on 24th January 1971. Among many problematic consequences and inevitable traffic jams, there was the proximity of the new structure to the buildings, with an average distance of only 5 metres. The ground floor of all buildings in the entire length of the “Minhocão” would be deprived from sunlight; all the local commercial activities and residential inhabitants would struggle with high levels of pollution and noise19 . All that would cause instant economic devaluation of the area along the elevated highway and the degradation of all the architectural heritage and the local pre-existing cultural activities (fig. 8). As a form of compensation for the many damages caused to the local quality of life, in 1976, only five years after the inauguration of the “Minhocão”, new laws were implemented for the daily closure of the road at night. In 1989, the City Hall determined its total traffic ban on Sundays, leaving it open to the population. The use of the road by pedestrians for leisure, although a positive initiative, generated both lack of privacy for the residents whose windows were at the same level of the highway, and awkwardness to the people who would walk flanked by blind façades turned into billboards.

The transformation of a symbol through the attribution of new values

The process of re-democratization of Brazil after the fall of the dictatorial regime led to a new Federal Constitution in 1988. The overcoming of an autocratic period of censorship and suppression of cultural expressions required a political effort of acknowledging and interpreting National Culture as a collective heritage connected to the memory of all the social groups that compose a culturally plural, diverse, yet deeply unequal Brazil (art. 206).

The dismissive role the imposed presence of the “Minhocão” had in the centre of São Paulo caused harmful transformations which, however, triggered a slow movement of reoccupation of the area, specially by workers in search of lower rent and small commercial and service businesses. That ended up guaranteeing the maintenance of a certain urban life, preventing the built heritage from ruin and demolition. During the decades that followed the construction of the “Minhocão”, the presence of such popular groups spontaneously established special cultural practices related to “ways of doing, creating, living and manifesting”.

As soon as the first urban policies were implemented towards the limitation of traffic on the “Minhocão”, there was a gradual appropriation of its space by the population for the practice of sports and cultural activities (open air music and theatrical performances, film projections, fairs and art exhibitions), until the elevated highway became a consolidated option for public leisure in the city centre (fig. 9). Starting from such spontaneous uses of the urban space, in the last decade we have seen the creation of neighbourhood associations, such as the “Associação Parque Minhocão” (Minhocão Park Association, 2013) and the “Movimento Desmonte Minhocão” (Minhocão Dismantling Movement, 2015), groups formed by professors, students, architects, environmental and culture activists, artists and others, which stand in contrary positions regarding the fate of the elevated structure. The former group defends the transformation of the infrastructure into a linear park; the latter defends its complete demolition for the appropriate requalification of the historical avenues below. It becomes clear the complexity that involves the fate of the “Minhocão”, which accessibility and fruition is nowadays managed in a collaborative manner by the municipality, the civil society, as well as by the private initiative. Due to such practices, in 2014, the Strategic Master Plan for the city of São Paulo established that “a specific law must be elaborated determining the gradual restriction of individual motorized transport on the Elevado Costa e Silva, defining deadlines until its complete deactivation as a traffic route, its demolition or, partial or complete transformation into a park”20.

Since the local social groups were empowered with the support of public policies, there has been a great pressure for renaming the elevated structure, resulting into a municipal decree that officially changed its name from “Costa e Silva” into Elevated Highway President João Goulart, a reference to the last democratically elected president deposed by the military coup in 1964. The aim of the 2016’s decree was the ratification of History and celebration of democracy. Following the lead, the Municipal Park of the “Minhocão” was legally instituted in 2018, to be managed by a popular council; and in 2019 the Municipality announced the plan for the deactivation of the elevated highway for its transformation into a linear park by 2030, although its fate is still to be determined.

The “Minhocão”’s fate and the role of public participation

By understanding tangible heritage essentially as a support and vector of values attributed by the social groups themselves, it can no longer be defined by its institutionality, constituted by discretionary action of the State and then, legitimized by an “official” heritage discourse. It is fundamental to consider a displacement of the valuation matrix in which society is recognised and empowered as the generator of values assigned to the built heritage. Therefore, the public institutions should keep a declaratory and protective role, yet always working in collaboration with the community, since all identity bonds associated to tangible heritage are sewn through daily and collective action, based on experiences and memories rooted in defined places21.

In order to better understand the social phenomenon related to the cultural appropriation of the “Minhocão”, the Repep (Paulista Heritage Education Network) in collaboration with the “Movimento Baixo Centro” elaborated the participatory inventory “Minhocão contra Gentrificação” (Minhocão against Gentrification). The inventory followed the methodology developed by the IPHAN (Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage) for Participatory Inventories, aiming to identify and map the existing cultural references in the city centre of São Paulo which are directly or indirectly impacted by the elevated highway. The survey of cultural references is fundamentally connected to the understanding of places and its ways of living, its collective uses, its ways of appropriation, as well as the different narratives that are built on that specific piece of territory; therefore, cultural reference is understood as everything that embodies sense and meaning to social groups, it is what guides the existence and constitutes their identity; it is an essential component of collective memory that expresses the way people live in a territory22. The data survey for the inventory started in 2015 and its first results were published in 2019. At that time, 45 cultural references had been mapped and classified in six categories: knowledge (know-how, ways of doing, crafts); forms of expression (ways of being and communicating); celebrations (rituals and festivities); places (spaces that constitute material support for cultural practices); buildings (architecture with symbolic and memorial values); and objects (work instruments and utensils with memorial value).

Within the mentioned categories for cultural references, it is important to highlight: social movements for housing, against racism and gender discrimination, which are valuable examples for their know-how on ways of popular organisation and collective action; street theatre groups which main aim is to widen the access to culture through an interactive and mobile approach; religious processions linked to dancing and cultural practices; row houses, as remaining documents of the typical ways of living of the first decades of the 20th century; among others (fig. 10). As previously mentioned, the range of groups and practices that have the “Minhocão” as a material reference for their expressions may also create tensions due to conflict of interests and the different ways the cultural heritage is interpreted by each group. In fact, the recent municipal decree towards the deactivation of the highway is broad in its guidelines, since the discussions related to its possible demolition or its transformation into a park are still intense in the political instance. On one hand, the decision for keeping the structures of the “Minhocão” brings with it serious difficulties regarding the requalification of the historical avenues and squares currently decayed. On the other hand, the decision for the demolition of the “Minhocão'' could mean the annulment of many of the political and cultural achievements hardly earned by local groups in the last 60 years, weakening their organisation structures and triggering gentrification. However, one thing remains clear, constant transformation is inherent to cultural references and collective memory, which means that the interpretation of cultural heritage will always keep a substantial degree of subjectivity.

In conclusion, it is fundamental to acknowledge that the spontaneous uses of the spaces defined by the “Minhocão”, associated with the consolidation of empowered civil organizations, manifest a strong sense of social and urban resilience. The necessity for coexistence of the local community and the imposed infrastructure conditioned the population to attribute new values to the highway, transforming it into a place of reference for cultural expressions and political activism. Such a resilient attitude towards the highway as a historicised element led to non-destructive policies for urban regeneration and the generation of new intangible heritage. That is a clear case in which the product of an autocratic discourse is deeply redefined by social engagement into a symbol of a more egalitarian way of governance.

The legitimisation of cultural heritage discourses

Beijing’s City Walls and São Paulo’s “Minhocão” are significant urban linear structures within historic cities, both carrying controversial symbolic values attached to the discourse that originally legitimized them. While Beijing’s City Walls were constructed as the material representation of an imperial authority, the construction of the “Minhocão” expressed a sense of modernity in a period of economic growth during the first years of an autocratic government still in affirmation. In the mid-twentieth century, in both cases, the antithetic actions of destruction and construction were then justified by a need for modern urban development. Half a century later, whereas Beijing’s and São Paulo’s citizens continued to deal with the effects of such changes, the social meaning of both structures muted into something new.

In Beijing, the City Walls were intrinsically linked to the aspiration of transcending an autocratic past and breaking free from imperial rule, thereby crafting an image befitting the People’s Republic of China. The involvement of citizens in the Wall's destruction reflects a temporary confluence of interests within a social context of economic need and the necessity for urban expansion, underscored by a symbolic yearning for new urban life. While the lack of integrity of the City Walls is interpreted as a deep loss of connection to China's glorious cultural past nowadays. In order to recover that bond, the current need for the reconstruction of the Walls became an issue to be seriously considered and accomplished by the government. That is the reason why the current reconstruction process does not comprise the entire length of the walls, but specific sections and some of the most representative city gates were chosen as symbols of the urban history. In São Paulo, the decay of urban and architectural heritage is similarly tied to the affirmation of a new regime. What had been destroyed for the construction of the “Minhocão” has, nowadays, become a secondary concern, and the structure itself acquired an unforeseen role for the creation and maintenance of practices celebrated as intangible heritage. In this way, the local social groups legitimized the preservation discourse regarding the elevated highway, transforming it into a new kind of urban heritage, away from a destructive or reconstructive approach.

Despite the discrepant contexts, Beijing’s and São Paulo’s case-studies clearly demonstrate that the maturation of values attributed through coexistence may subvert narratives, underscoring the utilisation of cultural heritage as a tool for symbolic discourses in constant change.

Collective memory and its transformative potential

Collective memory refers to a complex social process in which a society or social group constructs and reproduces its relation to the past. As Rossi declares, individuals create strong cultural images while experiencing the city, and major changes in the physical environment can cause discontinuities in collective memory and lead to historical amnesia23.

Several scholars have adeptly traced how personal memories undergo transformation into collective memories, often under the influence of political interventions. This transition is notably exemplified through “official” acts and commemorative artefacts24. The reconstruction of Beijing’s City Walls through official acts, in fact, aims to rebuild national identity and reshape personal memory into collective memory. Therefore, the cohesion of one nation becomes both an object and a locus of national identity, preserved through various memorial forms devised especially by state institutions and encountered as places of memory in people’s individual daily and public rituals25. Moreover, ruptures in collective memory can evoke nostalgia and melancholy26. Individual attachment to past forms is a factor of social unity, thus, collective memory plays an important role in the process of creating and reconstructing a community’s identity, and it can positively impact the conservation of cultural heritage, especially when it finds the necessary political support for the elaboration of more inclusive public policies.

In the meanwhile, individuals possess the ability to attribute new values to objects and spaces over the destruction of old ones, creating new narratives which better represent their civic will. As demonstrated in the “Minhocão” case, the participatory movement in São Paulo paved the way to the cultural requalification of the elevated highway and the generation of a new collective memory. As observed, such anomalous conditions caused by destruction could still form spaces susceptible for public appropriation, where different social groups could express their creative and transformative power. The construction of the “Minhocão” caused a physical trauma in the urban fabric of the city and also destroyed the ongoing formation of collective memories attached to the city’s historical centre. However, there was a public endeavour to heal that urban wound, and the local citizens dealt with that scar by reattributing new cultural values to it, recreating a remarkable bond. The uniqueness of the Brazilian case is that, after decades during which the regeneration of the collective memory of many social groups had been attached to the elevated highway, a wish for its preservation and transformation has been fomented, rather than for its demolition. The people’s perception of the city centre had been changed, and many groups could no longer conceive that area without the “Minhocão”. For that reason, it is possible to affirm that the elevated highway ended up acquiring a more relevant social and cultural role than the suppressed historical avenues below, exactly because its existence guarantees, up to a certain level, the cultural practices recognised as intangible heritage to be safeguarded and passed on. Interestingly, this peculiar preservationism gained a significant space within the city’s collective imagination, precisely due to the new meanings configured by spontaneous urban occupations, laden with democratic values related to the exercise of citizenship.

The duality of the participatory process for the protection of Cultural Heritage

Public participation plays a key role in the interpretation of cultural heritage. However, it is noteworthy that a participatory process is complex and can potentially be either constructive or detrimental, as evidenced by the two contrasting cases presented. The understanding of such duality is crucial for the elaboration of public policies towards a sustainable urban development aligned with cultural preservation.

In the Chinese case, some citizens actively participated in the destruction of Beijing's City Walls, often unaware of their urban historical value. This phenomenon needs to be contextualised within China’s historical background, where the establishment of a new government frequently goes hand in hand with the dismantling of structures associated with the previous regime. Here, the symbolic meaning of a monument usually overweighs its authenticity or historical value and remains intricately tied to the public sentiment. In the 20th century, the public involvement in the demolition process was aligned with the governmental objectives to modernize the capital city.

Considering the Brazilian context, it can be observed a tendency towards the resignification of symbols and the reattribution of values as a way of survival for the cultural heritage. For the “Minhocão”, transformation has been considered before destruction, legitimized by local social groups before the acknowledgement by public institutions. However, it is important to point out that the discourse of the governmental institutions after the redemocratization were aligned with the principles of recognition of national cultural diversity, which empowered the civil society to actively participate in the decision-making process through participatory inventories, important tools for the collaborative safeguard of tangible and intangible cultural heritage. The actions of people in defence of their right to exist and express themselves were given high priority, and these actions became an integral part of the heritage value. Here, heritage relies in its intangible realm, and its recognition by the Brazilian policies are aligned with the principles expressed in the annals of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (Paris, 2003), in which intangible heritage “is constantly recreated by communities and groups in response to their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, and provides them with a sense of identity and continuity, thus promoting respect for cultural diversity and human creativity”27. The document mentions, thus, the importance of safeguarding measures by the State encouraging a participatory process in the different phases of research, inventorying, education, transmission and management of the cultural heritage, and it has been that methodology responsible for the positive unexpected results regarding the cultural fate of São Paulo’s “Minhocão”. In other words, conserving cultural practices and their material support means, essentially, the creation of people-centred policies in which divergences and conflicts are natural fuel for an everlasting production of new heritage roots.

Having made the above considerations, discussions continue on the current cultural processes going on in Beijing and São Paulo, and some questions remain.

Destruction, in effect, has always played a crucial role in the life cycle of Cultural Heritage, especially when it comes to sharp transformations in historic cities due to the modern urban development programs globally implemented during the 20th century. The rapid and continuous progression of such transformations often begets the voluntary destruction of historical cityscapes, with important consequences on how people perceive the city and how collective memory is bound to the city’s cultural past. In Beijing, the collective memory is constructed through institutional acts, while in São Paulo we observe the formation of new cultural roots from a destructive urban infrastructure. The understanding of destruction can be nurtured from both a tangible and intangible approach. Urban transformations imply discontinuities on the relation a society has with its cultural past, and within a few generations, cultural values are changed, and in some cases, it would be natural to observe social movements attempting to re-establish lost historical bonds. The act of destruction holds, indeed, a dual nature. On one hand, it may disrupt the continuum between the past and the future, potentially severing historical narratives and physical links; on the other hand, destruction may raise unforeseen opportunities for the rejuvenation or even the cultivation of collective memories linked to the formation of new cultural identities.

notes

Sirén,Osvald. 2014. The Walls and Gates of Peking. Translated by Deng Ke. Beijing: Beijing United Publishing Co., Ltd.

Li, Xiaocong. 2003. “Tangdai chengshi de xingtai yu diyu jiegou: Yi fangshizhi de yanbian wei xiansuo [The Form and Territorial Structure of Tang Dynasty Cities: Taking the Evolution of the Block-Market System as the Thread].” In Tangdai diyu jiegou yu yunzuo kongjian [Territorial Structure and Operational Space in the Tang Dynasty]. Shanghai: Shanghai Cishu Publishing House.

Baidu Baike. n.d. “Beijing City Walls.” Accessed August 20, 2023. https://baike.baidu.com/item/北京城墙/4491301?fr=ge_ala.

Beijing Municipal Office. 1919. Jingdu Shizheng Huilan [Beijing Municipal Overview]. Beijing: Jinghuang Printing and Publishing Company.

Zhu, Qiqian. 1914. Xiugai Jingshi Qiansanmen Chengyuan Gongcheng Cheng [Modifications to the City Walls of the Former Three Gates of the Capital].

Beijing Local Chronicles Compilation Committee. 2006. Beijing Zhi, Wenwu Juan, Wenwu Zhi [Beijing Chronicles, Cultural Relics, Volume Cultural Relics]. Beijing: Beijing Press: 339.

Shehui Ribao [Social Daily], November 18, 1924.

“Nanbei Xinhuajie Kaidong Zhi Tiyi [Proposal for Open Holes on the City Walls for South and North Xinhua Streets].” Beijing Daily, December 6, 1921.

Li, Shaobing. 2006. “1912—1937 Nian Beijing Chengqiang de Bianqian: Chengshi Juese, Shimin Renzhi Yu Wenhua Cunfei [Changes in the City Walls of Beijing, 1912-1937: Role of the City, Citizen Perceptions, and Cultural Survivals]”. Lishi dangan, no. 3: 113-120.

Huangchengyuan Jiang Gengxu Chaihui: Beijing Jiaotong Zhi Jiayin [Imperial Walls Will Continue to be Demolished: Good News for Beijing's Transportation].” Beijing Daily, November 20, 1924.

Li, Hao. 2023. “Zhongguoshi Xiandaihua Shoudu Guihua Jianshe de Zhongyao Tansuo [An Important Exploration of the Planning and Construction of a Modernised Chinese-style Capital].” Beijing Daily, April 25, 2023. https://view.inews.qq.com/k/20230425A014O900?no-redirect=1&web_channel=wap&openApp=false.

Liang, Sicheng. 2001. “Guanyu Beijing Chengqiang Cunfei Wenti de Taolun[Discussion on the Preservation or Demolition Issue of Beijing City Wall].” In Liang Sicheng quanji [Complete Works of Liang Sicheng]. Beijing: China Building Industry Press.

Beijing Municipal Committee of the CPC. 1953. “Zhonggong Beijing shiwei guanyu gaijian yu kuojian Beijingshi guihua caoan de yaodian. [Key Points from the Beijing Municipal Committee of the Communist Party of China on the Reconstruction and Expansion of the Draft Urban Planning of Beijing City].” November 26, 1953.

Kong Xue. 2018. “Huiyi: Woshi zenyang chaidiao Beijing chengqiao de [Memories: How I Tore Down Beijing's City Walls.]” BJNEWS, December 10, 2018. https://www.bjnews.com.cn/detail/154444570914964.html.

Mao, Zedong. 1977. “Fandui Dangnei Zichan Jieji Sixiang [Against the Bourgeois Ideology in the Party].” In Mao Zedong Xuanji [Selected Works of Mao Zedong]. Beijing: People’s Publishing House.

Neves, Deborah Regina Leal. 2018. “O Minhocão como expressão autoritária em São Paulo.” Clepsidra. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios sobre Memoria 5, no. 9: 52-67.

Pátio do Colégio, a Jesuit settlement with church and school that marks the foundation of the city of São Paulo in 1554.

Bouvard Plans, partially implemented in São Paulo by the French architect and urban planner Joseph-Antoine Bouvard (1840-1920), adopting Camillo Sitte’s premises for the conservation of historical centres.

“A Justiça condena o Minhocão.” O Estado de São Paulo, March 1, 1973.

Municipal law n. 16050, art. 375 - São Paulo, July 31st, 2014. Quotes freely translated from Portuguese by the authors.

Scifoni, Simone. 2019. “Interpretar qual Patrimônio? A experiência do Inventário Participativo do Minhocão, São Paulo.” 3rd Scientific Symposium of ICOMOS Brazil, Belo Horizonte.

Ibid.

Rossi, Aldo. 1984. The architecture of the city. Cambridge Massachusetts: MIT press.

Shackel, Paul A. 2001. "Public memory and the search for power in American historical archaeology." American anthropologist (103.3): 655-670.

Pierre, Nora.1996. "From Lieux de memoire to Realms of Memory," Preface to the English Edition of Realms of Memory: Rethinking the French Past, ed. Nora, trans. Arthur Goldhammer, 3 vols. New York: Columbia University Press.

O’keeffe, Tadhg. 2016. "Landscape and memory: Historiography, theory, methodology." In Heritage, memory and the politics of identity. Routledge: 3-18.

UNESCO. 2003. “Text of the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Accessed August 22, 2023. https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention.

Giorgio Nepote Vesin Martina Ulbar

Maryia Rusak

Kalinka Janowski

Carlo Francini Vanessa Staccioli Gaia Vannucci