This article deals with the destruction of houses in Marseille, a Mediterranean city in the south of France, in the 18th century. From 1666 onwards, a project to enlarge the city was launched. Although it was originally an initiative of the royal authorities, aimed at housing an increasingly large population, the project was managed by the municipal authorities in Marseille, after a gradual takeover of the charges relating to the undertaking. A new city model was then presented to the population, without being offered to them, as the poorest people remained in the old districts. It was in this context that almost 900 houses, mostly located in the old city centre of Marseille, were demolished and then rebuilt from the end of the 17th century, in reaction to a new form of perceived insecurity.

On 15 January 1688, when the first results of the enlargement project became visible, the City Council decided that a report should be drawn up to list the ruinous houses that the authorities considered harmful to the embellishment of the city. Between 1688 and 1704, all the destruction of facades was the result of this report. However, from 1705 onwards, the inhabitants took up the procedure and began to denounce their neighbours' houses. However, rather than the beauty of the urban setting, the argument of safety was mobilised. There was therefore a change in the usefulness of the procedure, as shown by the police order of 26 March 1718, which ordered the owners to demolish their ruinous facade "to avoid falls and accidents". We can therefore see that the inhabitants, by appropriating the procedure, were able to modify the municipality's perception of the urban space. Until the end of the century, ruinous houses will be perceived as dangerous by the ordinances, and not only as unsightly. The figures we have corroborate this idea: 79% of the procedures leading to destruction in the 18th century concerned a house in the old town. These procedures are, moreover, initiated by neighbouring groups formed specifically to denounce a common danger to their safety.

From the town planning and legal archives in the municipal archives of the city, we can demonstrate that the laws and guidelines for town planning were directly influenced by the inhabitants, and not only by the large-scale development projects.

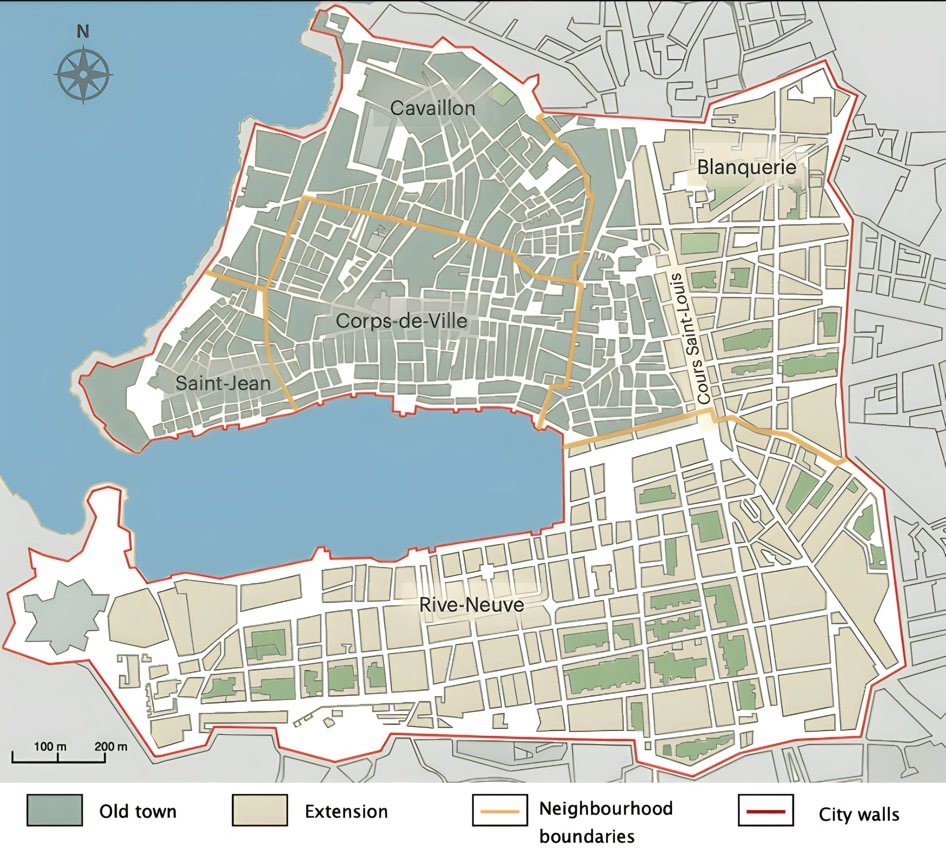

In the second half of the modern era, the royal power was the driving force behind a specific urban policy which had a profound impact on the structure of towns and cities1. On the whole, the reign of the Sun King was marked by the embellishment of large urban areas, a process which continued under Louis XV. In Marseille, after the signing of the treaties ordering the project in 1666, work began to extend the city to the north and east2. In contrast to the "old town"3, a completely new district was built according to a new architectural model: wider streets, standardized houses and the creation of the Cours Saint-Louis4. This model was the same as that used in other cities of the kingdom5. At the same time, the Cours Mirabeau was built in the centre of Aix to improve the urban environment. In Marseille, on the other side of the Cours Saint-Louis, a suburb was urbanised and incorporated into the city by moving the city walls6.

This extension serves a dual purpose, both aesthetic and political. The population of Marseille was growing at such a rate that the city was running out of housing. Although the plague of 1720 wiped out almost 40% of the population (around 35,000 inhabitants)7, by the end of the 18th century, the city had more than 100,000 inhabitants. Expanding the city therefore became a necessity, and the management of this undertaking was granted to the city council by letters patent in 1660. The municipal authorities were therefore responsible for the works and for establishing the body of regulations that they entailed.

It was in this context that a new form of legal procedure gradually developed, one that did not exist before 1688: house demolition proceedings. The municipal archives of the city of Marseille list more than 900 proceedings that took place between 1688 and 17898, on the eve of the French Revolution, demonstrating a change in the interest shown in preserving buildings and securing the physical urban space.

At the end of the 18th century, the Marseilles linguist and lexicographer Jean-François Féraud defined security in contrast to safety9. Whereas security is more a matter of sentiment, safety aims to ensure the integrity of body and mind, and therefore involves concrete solutions. So, if we follow the author's thinking, the concept of 'securisation' is closer in definition to safety than to security. This is because it is indeed 'safety' that is referred to in Marseille's modern-day archives. This study looks at the question of security from the angle of one of its practical applications. While the underlying concepts are not forgotten, we felt that it would be more appropriate, in a study of a historical discipline, to use the sources available to us to look at the concrete choices made to provide security in response to need. The aim of this study will therefore be to approach safety as a fundamental need, recognised by an authority that translates it into decisions concerning the city and impacting on the lifestyles and residences of its inhabitants.

Using this corpus of sources, this study proposes to examine the ability of residents to participate in shaping the city they live in, including in the context of a construction project leading to a codification of spatial law. In fact, the expansion project is both the context and the driving force behind a change in the way the people of Marseille perceive the materiality of the city. This change involves emotions, expressed in a lexicon and rhetoric of safety.

Our aim is to highlight the key role played by residents in shaping the city. The corpus chosen for this study therefore only includes demolition procedures that were prompted by a complaint from the neighbours of the house concerned, and not all the renovations carried out by the municipality, which in particular provided an opportunity to align the streets. These are listed in comprehensive registers that do not, however, begin until 172710, the date on which the project to align the streets of the old town was started, after a "geometrical and general plan of all the alignments and rectifications of the streets and public squares of the town and suburbs of Marseille" had been drawn up on 29 May 172511. In fact, our archives seem to be recorded in this way: the corpus we are dealing with in this article is made up of all the demolition procedures initiated before 1727, as well as demolition procedures initiated by residents of the city after this date. The remaining works, most of which were no longer police procedures but immediate condemnations as part of the implementation of the geometric plan of 1725, are listed in registers that could be the subject of another study, in particular on the impact of the plague on the town planning project carried out by the municipality.

A standard procedure generally works as follows. Neighbours, sometimes accompanied by passers-by, report the condition of a house that they consider to be a danger to their safety to the town's police chamber12, where the commissioners sit. A commissioner is appointed to visit the site with a mason from the community or the town architect. Together, they check the inside and outside of the house, sometimes requesting additional information from the neighbours present (if there have already been any landslides, for example) and decide whether demolition is necessary. The King's Public Prosecutor then requests the demolition and the sentence is handed down the same day or the next day by the aldermen. If the owner is not summoned to hear the sentence, it is the bailiffs who are responsible for informing the owner. They then leave a written record following that of the aldermen to certify that this has been done.

While urban renewal is not a case specific to the city of Marseille (fig. 1), and should be seen in a national context as an example of an expansion project driven by the King of France, these archives are unpublished. Indeed, no similar documentation seems to have been studied for any other urban centre in the kingdom. Similarly, while the plague is specific to the context of Marseilles13, the archives we are dealing with here, produced by municipal officials and building experts, do not cite it as a driving force in the procedure, unlike the embellishment of the city, which is an argument put forward by both the municipal authorities and the residents who went to lodge their complaints. One difference, however, is that residents tend to emphasise the contrast between new and old neighbourhoods, right from the first complaints. For example, the fact that a new part of the city is being financed before the existing part is renovated. In this way, the city's residents do not seem to link elements of urban materiality to the virality of transmission, as may be the case with complaints about odour-producing trades14. In the context of the demolition procedures that they initiated, the residents seem to link this more to their "safety", if we use their own words. The health aspect of their safety is therefore associated with odours15, not houses.

The city of Marseille is made up of four main districts. On one side is the old town, with its narrow, dimly-lit streets and ancient buildings, some of which date back to the Middle Ages. On the other, the new districts, built in accordance with the urban planning requirements of the 17th century, with buildings lined up in a uniform fashion, decorated with balconies, and streets lined with benches and trees. From the 1680s onwards, residents were confronted with this contrast.

Jean-Joseph Expilly, an ecclesiastic and author of a geographical dictionary, explains:

The city of Marseille is divided into an old town and a new town. The old town is on high ground, above the port, to the north, and is fairly poorly built. The streets are very narrow and some are very fast. The new town, on the other hand, is perfectly well built and well pierced16.

The expansion project thus carves up the city and provokes a necessary comparison between what is habitable and what is uninhabitable17. While the majority of residents, who also happen to be the poorest, continue to live in the old neighbourhoods, some of them are able to move into the new homes, which offer a lifestyle and living environment that are considered to be superior. The expansion of the city cannot be dissociated from its embellishment. The company's archives bear witness to the interest shown in the beauty of the urban environment. Every new development was supported, even if it meant further decorating the town. One example is the extension of balconies. Any homeowner requesting permission to install a balcony is allowed to do so, as long as the installation does not jeopardise the symmetry with the neighbouring houses18. In addition, every town in the kingdom with a similar project at the time also used the term "embellishment" in its regulations19. Finally, the two terms, enlargement and embellishment, are used interchangeably in the archive documentation, allowing us to confirm that we are dealing with one and the same project.

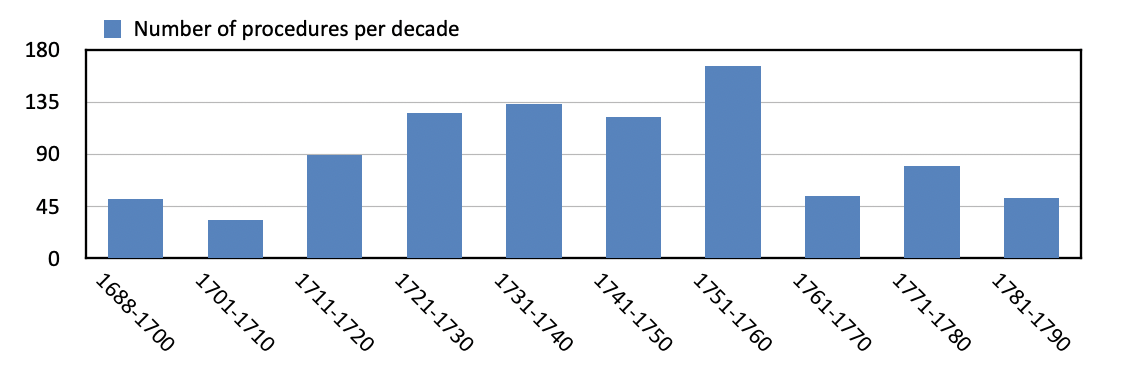

The house demolition procedure is, in the form that it takes, a novelty specific to the end of the XVIIe century, which can be explained by the context of the town's embellishment. We find 51 procedures recorded between 1688 and 1700, 33 in the first decade of the eighteenth century, 89 in the second, 126 in the third and 133 in the fourth. This increase is evidence of a growing interest in the risk of collapse. Also, the almost forty years between 1723 and 1760 are those with the highest number of proceedings. They thus represent the sustained period. After 1760 and until the end of the century, the number of proceedings per decade fell to between five and eight per year.

So, to sum up, there is a gradual interest from the end of the 1680s, followed by forty years of intensive monitoring, a major decade in 1750 with 166 procedures and finally a quieter period from the 1760s onwards. However, the number of procedures in these last two decades shows us that interest in the physical safety of streets and houses is still very much alive (20.5% of procedures took place after 1760). These figures show a logical decrease, since although all the proceedings between 1688 and 1760 resulted in rebuilding, the city of Marseille is safer, as the number of houses in it remains the same. The gradual decline in the number of convictions may therefore seem consistent.

However, this first graph (fig. 2) does not show an important point in the history of Marseille in the 18th century. There are no cases between 1719 and 1723. These are the chronological limits of the plague, which put this concern for the safety of buildings on hold and changed their relationship with each other20. The figure for the 1720s is therefore all the more impressive if we take into account the fact that these 126 procedures were spread over just eight years. This is an additional element that shows this new interest in the safety of the city's buildings, in the safety of the street and the home.

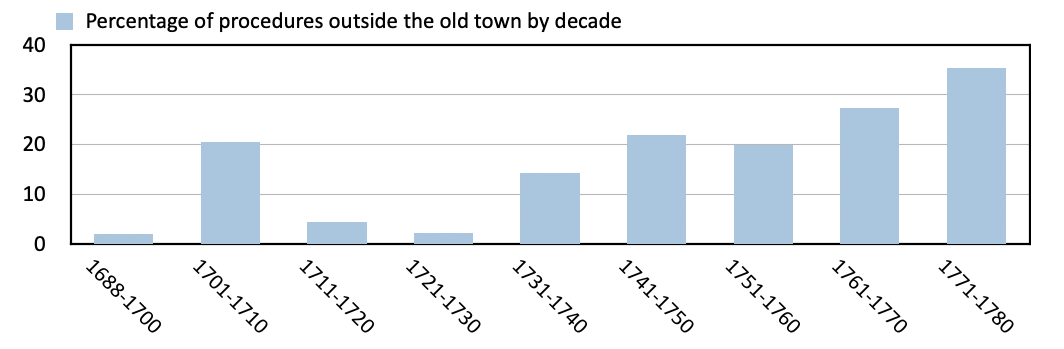

If we look at the long-term trend in the number of proceedings outside the town centre, we can see that they have become increasingly numerous over time21. While they represented less than 11% of proceedings up until 173022, they gradually gained in importance, reaching a maximum of 28% of proceedings in the 1770s. We can therefore observe an increase in interest in houses outside the old town, which can be interpreted as a shift in focus from the houses in the centre to the more peripheral buildings. It is conceivable that, having dealt with the most notoriously deteriorated houses, the authorities would turn their attention to other, more outlying areas. It was also during the 18th century that the town began to expand, with the number of inhabitants and buildings increasing significantly (fig. 3).

While the first part of this article enabled us to study the figures for demolition procedures and thus establish the importance they have assumed over a century, two other indications allow us to affirm that the inhabitants of Marseille are seizing this procedure and using it to assert their rights as residents. The first important piece of information is that all of these — with a few exceptions23 — began with a complaint from the neighbours of the ruined house, who felt threatened by the possibility of a collapse. Also, as the town centre is older, the streets are narrower and the houses are closer together. For this reason, the danger felt from the possibility of a collapse is accentuated. As a result, almost 80% of the procedures recorded are directed against a house located in the old town centre.

By extension, we can conclude that residents do not hesitate to denounce a house in their neighbourhood if they consider it to be dangerous to their safety. However, the procedures did not immediately take on this safety objective and were originally more the product of municipal thinking on embellishing the town. In fact, on 7 September 1686, when the first contrasts between the old town and the extension were becoming apparent, the Town Council decided that a report should be drawn up listing the damaged houses in the old quarters24. This was supposed to enable it to order their demolition, followed by reconstruction in accordance with the alignments decided beforehand, and thus embellish this part of the town. The first condemnations resulting from the report began in 1688, after validation by the Court of Parliament. Between 1688 and 1704, 64 houses were condemned, systematically as a result of the report drawn up by a commissioner and a master mason from the town.

Gradually, residents seem to be taking this procedure on board, understanding the importance it can have for the municipality. They denounce houses in a state of ruin directly, but use the argument of safety rather than that of embellishment. In fact, in their denunciation, carried out collectively after consultation between members of the same neighborhood, the residents denounce the daily risk represented by a house in a state of ruin, located so close to their homes and whose landslides could injure them. Between 1705 and 1717, 96 houses were condemned, 77 of them as a result of complaints from neighbours. For the last three years, all of the cases came from this type of denunciation. This led to a general ordinance on 26 March 171825. Although it largely repeated regulations that had already been laid down but were not respected by the inhabitants, article XI was a novelty in that it required every owner of a house in danger of collapse to have it demolished and then rebuilt, in order to "avoid falls and accidents"26. This measure does not address the issue of embellishment, but rather that of safety, in order to justify the measures it imposes. So here we have a consensus between the residents, who had a direct influence on what the municipality said, and the municipal authorities, who thought they could ensure compliance with the ordinance by presenting it to the residents according to their own criteria. Subsequently, between 1718 and 1789, all proceedings were the result of a complaint from the neighbourhood.

The urban context of the company we are studying is one of expansion that has created a visual opposition between two urban spaces, the old and the new. The population remains the same, however, has simply shifted and spread out, uniting two very different areas into one city. This is a time for legibility and the imagination of a city whose practices have been smoothed out27. Walking around the city is encouraged, if only by the form given to the new objects taking their place in the most recent part of the city, by markers28 implicitly encouraging the association of ideas through the creation of a system of references29. The municipal authorities are responsible for these markers, which reaffirm the definition of each urban object. This begins with a multiplication of scales, a superimposition of names given to different forms, different spaces, supposed to be contained by the city and to define it, visually and theoretically: extension, "oldest part of the city", districts, blocks, streets. There are many different scales of location in the municipality's sources, as are the rules governing them.

The street, like the courtyard, is a neutral territory under the domination of a single power, now falling within the public domain, itself explicitly defined by the creation of sub-categories of regulations in force in the city: "public tranquillity", "public health" or "public road"30. By extension, the police are going to define their own role, and henceforth aim to enter all areas of what is considered to be public; spaces are thus directly concerned. In theory, public spaces are those in which the police have control. This legal definition of public spaces is the product of more general thinking, a definition constructed by the royal power and gradually disseminated through enlargements and changes in police practices, whereby there is now a separation between a private domain and a public domain in all aspects of society: behavior, law and space. For residents, the public domain is defined quite simply as a right that is the same for everyone, and which is ultimately non-existent, or at least largely under the yoke of municipal authority. As far as the space is concerned, it is ultimately a question of emptiness, of a long operation aimed at removing everything that detracts from its public character; from facilities to attitudes alone, everything is considered.

Within this general framework, demolition procedures aim to embellish the urban environment but cannot occupy its streets for too long. It's a paradox that explains the short timeframe given to owners to rebuild their facades.

After the ordinance of 1718, the standard procedure was generally as follows. Neighbours, sometimes accompanied by passers-by, reported the condition of a house they considered dangerous to their safety to the town's police chamber31. A commissioner is appointed to go to the site with a mason from the community or the town architect. Together, they check the inside and outside of the house, sometimes requesting additional information from the neighbours present (if there have already been any landslides, for example) and decide whether demolition is necessary. The King's Public Prosecutor then requests the demolition and the sentence is handed down by the aldermen on the same day or the following day. If the owner fails to appear when summoned to inform them of the sentence, the bailiffs are responsible for informing them. They leave a written record following that of the aldermen to certify that this has been done. Once the sentence has been passed, the owner has eight days to repair the house. They also have the option of responding by appealing against the sentence and requesting that it be postponed or cancelled.

Neighbours often complain about falling rocks when they go to report the incident to their local superintendent. While this may at first appear to be an exaggeration, the reality is certainly close. The old town of Marseilles is made up of old houses inhabited by poor people who rent and change flats as soon as a cheaper rent is found32. As in all of France's major urban centres in the 18th century, the one-room flat encouraged people to spend more time outdoors, in the streets of the city and the neighbourhood. So there was a kind of concordance between the way of life and the type of repairs chosen: temporary repairs to match changing lifestyles.

What's more, real in-depth work would take too long and would raise the problem of financing, as simply repairing a facade is already an expensive investment for owners. According to Daniel Roche, these types of repairs, which are not sustainable in the long term, whether they are carried out by the authority or the owner, reflect the fact that poor people in old towns are still poorly housed33.

By extension, we can clarify the idea behind the authority's concern for the safety of the built environment. While it is indeed a concern for the built environment of the town, the population that is being protected is not just the tenants and residents of the houses that are in danger of collapsing. In fact, interest is focused on these buildings because they represent a danger to a larger population, in particular the neighbours. The focus is actually on the street and not on the inside of the house34. This is clearly seen in the demolition procedures, which, when carried out on houses in the old town, only concern the façade facing the street, and not the foundations of the building. What's more, every mason's report concludes with the danger posed by the house to neighbours and passers-by. The authorities were not concerned about the safety of the few inhabitants of a single house, but about the overall shape of an ever-growing population in a space that was not growing, with busy streets and buildings that could not do without the accommodation they provided.

In the mind of the Marseilles municipality, the definition of safety in the city's built environment is based on quantity and materiality. It is not interested in the quality of life of these populations or in improving it, but in maintaining the houses that already exist to house the poorest people. It was a question of maintaining the environment in which people lived, rather than a direct concern for the quality of life, as demonstrated by the impressive number of façade works carried out throughout the 18th century. No improvements were envisaged, as this mode of operation certainly seemed the simplest. Between letting the part of the town that houses the majority of its population wither away and embarking on extremely costly and problematic works - since the residents whose homes were targeted would have to be housed - the choice was made to suspend time, to keep the viability of these foundations at a fixed point for as long as possible by means of minimal maintenance and short-term works.

A final point that may support this idea of an exclusively outward-looking perspective is the case of alignments. The municipality of Marseille defined these procedures in the primary sense it had given them since 1688, to embellish the town. We finally arrive at a form of compromise through the ordinance of 26 March 1718 and a text employing a rhetoric of security, thanks to a common point in the respective perceptions of the residents and the municipality: an interest in the exterior and not a concrete concern for housing. While the residents were worried about their survival and the town was concerned about embellishment, both parties saw houses in danger of collapsing as an obstacle.

In this way, the municipality of Marseille kept in mind the primary objective of endowing the urban setting with a certain beauty, and took advantage of every procedure after 1718 to demand the alignment of the house that was to be rebuilt, enabling it to ensure a minimal form of embellishment of the part of the city that was most complicated to modify. To ensure this, the owner was compensated for the surface area lost by moving the façade back35, making him more inclined to accept demolition, since this implied a financial advantage. Under the guise of a text advocating safer urban spaces, the municipality's primary motivation remains the embellishment of the city.

In a context that follows that of the expansion of the city of Marseille, it is interesting to note that part of the city is visibly excluded from any desire for progress and embellishment. This initial analysis of the demolition procedures shows that they were not abandoned as soon as an owner failed to comply with his condemnation, but were repeated, several times and sometimes with an interval of several years, proof that the concern for the upkeep of these poor-quality houses was long-term. However, the repairs, which are more akin to DIY than real in-depth work, are only intended to keep them in good condition. These are therefore short-term repairs, which certainly also explain some of the repeated cases.

The study of façade demolition procedures in the eighteenth century was a starting point that enabled us to study a new form of protest by residents in relation to their safety, and allowed us to focus on the real capacity of residents to participate in the making of the city. We were able to see that the common interest of the residents and the authorities was focused on the street, rather than on the house itself. The concern is not to make the flat where you live safer, but rather the street, the neighbourhood in which you live. This can be explained by the way in which people live in the city in modern times: everyday activities take place outside, such as working, eating and socialising. This will have an impact on our understanding of place. Rather than thinking of themselves as living in a flat, people are residents of a street and a neighbourhood. There is no sentimental dimension to the relationship with the house, at least as far as we have been able to observe. Homeowners are certainly the ones with the most finely localised scale for reading place. However, the interest is purely economic. A house represents a cost, and in the old town more than elsewhere because of the low rents and the repairs required. It is therefore the owner's duty to keep abreast of the dangers that threaten his property, so that in the long term it does not represent the double burden of a loss of income and an expense. We must bear in mind that the corpus studied is made up only of proceedings that began with a denunciation and ended with a conviction. This raises the problem of the actual number of denunciations and proceedings initiated, which is certainly much higher than the number we have, as well as the number of convicted houses. This makes possible the idea of communication between the old town and the suburbs, which, aware of the success of this procedure, gradually took it over using the same arguments from the second half of the century, when it was at its height in the town centre. The sources tend to confirm this interpretation, as can be seen from the table showing changes in the number of proceedings outside the city walls36.

Finally, because the aim of this study was to establish the inhabitants' capacity for action in the construction of the town, it has restricted the corpus of its analysis to demolition procedures, excluding undertakings relating to the execution of the 1725 plan, which are recorded in the form of registers37 in the archives of communal property38. However, it is worth noting the potential of this other corpus, which, as it relates to the development of the town-planning project led by the municipality, would certainly enable us to shed light on the evolution of the latter's objectives and, in particular, to clearly place the influence of the plague on the town's town-planning context.

notes

Denys, Catherine. 2011. "Ce que la lutte contre l'incendie nous apprend de la police urbaine au XVIIIe siècle." Littérature et culture (1760-1830), no. 10: 17-36. In Rennes, for example, the town was rebuilt after the fire of 1720 (Nières, Claude. 1972. La reconstruction d'une ville au XVIIIe siècle. Rennes, 1720-1760. Paris: Klinchsieck).

Hénin, Béatrice. 1986. "L'agrandissement de Marseille (1666-1690). Un compromis entre les aspirations monarchiques et les habitudes locales." Annales du Midi: Revue archéologique, historique et philologique de la France méridionale 98, no. 173: 7-22.

See Figure 1.

See Figure 1.

Puget, Julien. 2018. Les embellissements d'Aix et Marseille: droits, espace et fabrique de la ville au XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. In his doctoral thesis, Julien Puget warns us that linking political and territorial events too simply can give impression that people are inactive in the face of changes to the space they occupy. What's more, a single explanation common to every case would be insufficient to grasp the local context. Each town has been embellished has done so in response to its own problems and context.

Ibid.

Beauvieux Fleur. 2017. "Expériences ordinaires de la peste. La société marseillaise en temps d'épidémie (1720-1724)." PhD diss., École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

Marseille municipal archives (AMM), FF274 to FF284, Houses in danger of collapse. Procedures, 1688-1789.

Féraud Jean-François. 1787-1788. Dictionnaire critique de la langue française. Marseille: J. Mossy.

AMM, DD85 to DD88, "Alignments and cuttings: registers" 1727-1789.

AMM, DD82, "Alignments and cuttings: general works" 1660-1789.

This is esplained in the archive files. A case begins with a report from the commissioners. They begin by introducing themselves, starting their name and position, and explaining that a neighbour had come to complain about a house at the police station. On the workings of the police in Marseille see: Marin, Brigitte, and Céline Regnard. 2019. Police ! : les Marseillais et les forces de l'ordre dans l'histoire. Marseille: Gaussen.

See in particular the studies by Fleur Beauvieux: Beauvieux, Fleur. 2014. "Justice et répression de la criminalité en temps de peste." Criminocorpus and Beauvieux, Fleur. 2017. Op. cit. On the link between plague and urban mateiralité see in particular the work by archaeologist Marc Bouiron: Bouiron Marc, ed. 2011. Fouilles à Marseille: la ville médiévale et moderne. Aix-en-Provence: Camille Jullian Center.

Several complaints from residents lodging an appeal against a neighbour whose business was causing "nauseating" odours, listed in the police registry records (AMM, FF302 to FF401), clearly establish a ling between odour and illness. However, even if in the case of these complaints the health argument is clearly spelt out, we cannot be sure that it is not simply a rhetorical argument aimed at convincing the city concil of the need to move these workers out of the urban centre.

Sénépart, Ingrid, ed. 2017. Aux portes de la ville: la manufacture royale des poudres et salpêtre de Marseille et le quartier Bernard-du-Bois. Genèse d'un quartier artisanal. Aix-en-Provence: Centre Camille Jullian.

Expilly, Jean-Joseph. 1766. Dictionnaire géographique, historique et politique des Gaules et de la France. Paris: Desaint and Saillant.

Canepari, Eleonora, Rosa Elisabeth, and Alice Sotgia. 2020. L'(in)habitable. Marseille: Imbernon Editions.

Bouches-du-Rhône departmental archives (AD13), C 5125.

Harouel, Jean-Louis. 1993. L'embellissement des villes: l'urbanisme français au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Picard Editions.

Beauvieux, Fleur. 2017. Op. cit.

See Figure 3.

See Figure 3.

79 procedures, all of wich took place befor 1718, were the result of a report drawn up by the municipality.

AMM, FF273.

AMM, 1BB1042, Ordinance of the city's aldermen, containing 38 articles of police regulation, 1718.

Idem.

Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Goffamn, Erving. 1973. La mise en scène de la vie quotidienne. Tome 2, Paris: Minuit Editions.

Ibid.

AMM, FF191, Compendium of regulations, divided into two chapters: town (31 articles) and land (11 articles), 9.

AMM, FF274-FF284.

Puget, Julien. 2018. Op. cit.

Roche, Daniel. 1981. Le peuple de Paris: essai sur la culture populaire au XVIIIe siècle. Paris: Aubier-Montaigne Editions.

Ménétra, Jacques-Louis, and Daniel Roche, Journal de ma vie. Paris: Albin Michel Editions.

AMM, FF274-FF284.

See Figure 3.

AMM, DD85-DD89.

In the municipal archives of Marseille, DD series.

Susan Holden

Ayla Schiappacasse

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Lorenzo Mingardi (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Jiayao Jiang Pedro Marroquim Senna

![Figure 1. Old town and extension districts, Marseille, 18th century. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France, Maps and plans department, GE C-1599, [http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40698023z]](https://adh.quivi.it/storage/app/uploads/public/652/8ff/7b1/thumb_262_0_0_0_0_auto.jpg)