In some instances, recourse to destruction can become a pretext to mark a new beginning, a restart. The decision to demolish marks a point of no return and is often part – and end – of a more complex and intricate process, involving difficult acceptances and acknowledgements, as well as possible reconsiderations and changes in direction fueled by both internal and external factors.

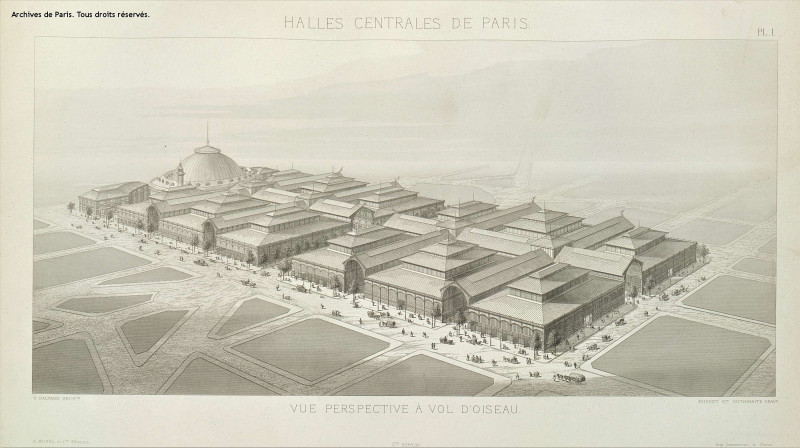

In a Paris that has just witnessed upheavals on the political and cultural fronts, overturned by new urban and territorial planning strategies, violent student protests, and the sudden rise of Georges Pompidou (1911-1974) to the Presidency of the French Republic, there is no shortage of opportunities for a substantial demolition campaign1. Two contiguous areas straddling the 2eme and 4eme arrondissements were especially affected by complex urban and architectural operations between the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. On one hand, these operations involved the demolition, begun in 1971, of the Paris market pavilions built by Victor Baltard (1805-1874) between 1852 and 1872 – which were considered obsolete – to allow the construction of the new RER (Réseau Express Régional) station Châtelet-Les Halles beneath «le ventre de Paris»2, and, on the other, the launching in in 1969 of a competition to determine the future use of the extensive area known as Plateau Beaubourg, which had been vacant since 19353.

The demolition action carried out in Les Halles has had a twofold effect, both by promoting actions and initiatives aimed at protection, conservation and preservation, but also by triggering a chain reaction of destruction. The case of the Square des Innocents and the fountain that stands at its centre is emblematic in this regard; during the dismantling operations, this jewel-like square was completely deprived of its trees, deemed too old to be transplanted, in favour of maintaining the position of the fountain and ensuring its complete protection throughout the entire yard, with the promise of returning the public space of the square entirely to pedestrians. The efforts made by public authorities to minimise the collateral damage of this massive architectural and urban operation are evident in the period between the decision to move and the actual relocation: between 1969 and 1971, the pavilions remained in operation and hosted a wide variety of recreational and cultural activities, allowing Parisians to explore Baltard's work, which was often inaccessible due to the site’s strict regulations. But the issue of renewing Les Halles also took on all the features of a human drama. A significant percentage of the buildings in the neighbourhood were in a dilapidated state, sometimes uninhabitable, and the population density, composed mainly of small artisans, was much higher than the Parisian average; from the early 1970s, evictions, as well as decisions to demolish entire buildings in the Beaubourg and Saint-Martin îlots, were substantial and continued even during the construction of the Centre Pompidou (1971-1977)4.

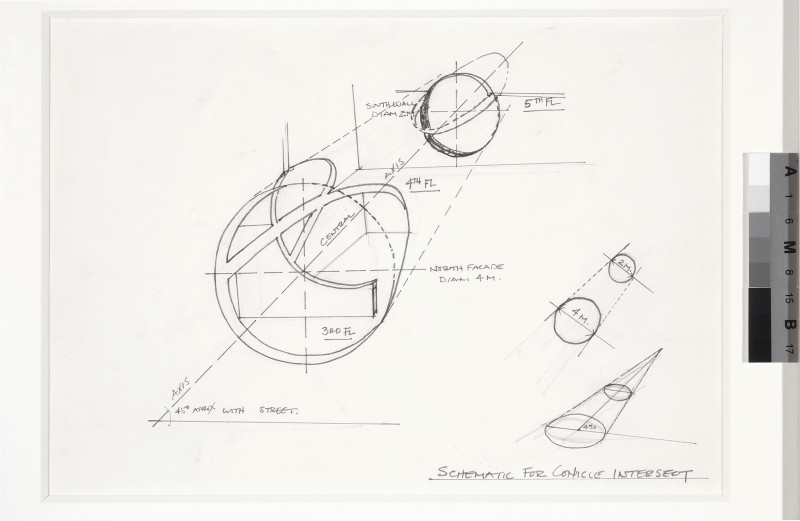

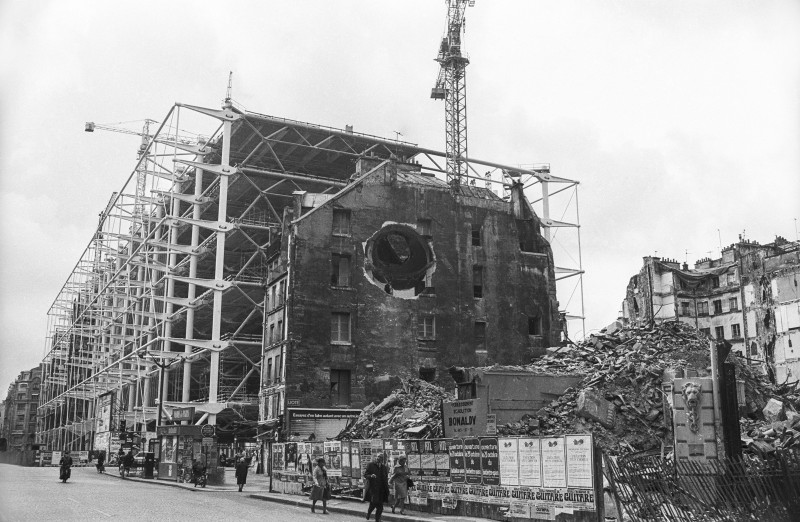

In 1975, in fact, the American artist Gordon Matta-Clark (1943-1978) was invited by the curator of the Musée National d'Art Moderne, Jean-Hubert Martin (1944-), to participate in the Paris Biennial, and he decided to install his artwork in Les Halles district, specifically within two 17th-century buildings, close to demolition, located at 27-29 Rue Beaubourg5. With Conical Intersect, Matta-Clark transformed his structure – and its demolition – into a communicative act, not only by placing a critical emphasis on the «Gaullist cleansing» operation, but also by capturing the spectator in a destructive vortex, making him a participant in the consequences of these demolitions and directing him towards the concrete result and the ultimate goal of the process: the Centre Pompidou6.

Information note from the office of the Prefect of Paris to the press on the dismantling of the Halles pavilions, PEROTIN /101/77/1 45, 13 May 1969 (Archives de Paris)

Office of the Prefect of Paris

Paris, 13.5.69

NOTE on the DISMANTLING of the HALLES PAVILIONS

The Les Halles pavilions built by BALTARD7 will be dismantled gradually.

The construction of the two superimposed Châtelet stations on the East-West regional line and the Sceaux line will require the removal of pavilions 7 to 12.

Initially, it will be necessary to simultaneously dismantle pavilions 7 to 108.

However, if pavilions 9 and 10 are not dismantled before the end of July, they can be used for the Festival du Marais, which begins on 3rd June and runs for a month9.

Pavilion 11 comprises almost 2,300 m2 of floor space per level, but part of this area will have to be reserved for passageways, cloakrooms and storage areas. In addition, some of the surface area will quickly become unusable due to the proximity of the excavations. However, the pavilion could be used for theatrical performances and various exhibitions. It would also be possible to install a small suite of shops.

Pavilion 12 is a replica of Pavilion 11, and its use poses more delicate problems, since it is assumed that any occupants will have to vacate it before the summer of 1970. However, it is planned to set up a permanent “Halles village” devoted to second-hand goods, where a number of exhibitions will also be held.

In addition, six pavilions located to the west of the carreau des Halles - pavilions nos. 1-2-3-4-5 and 6 - will only be vacated when the meat wholesalers leave10.

One of them, No. 6, which until now has been occupied by a number of fruit and vegetable wholesalers, will very shortly be reserved for the retail market, although this will not preclude the possibility of installing temporary sports facilities for local schoolchildren in the basement11.

Jean [?]

Gordon Matta-Clark, Descriptive text for Etant-D'Art pour Locataire or Conical Intersect, 1975 (Candian Centre for Architecture, Gift of Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark)

(ETANT-D’ART POUR LOCATAIRE) CONICAL INTERSECT

PARIS, ‘75

All earlier works used buildings neither as objects nor as art material but as uniquely cultural complexes in a given social fabric. These works that consisted of questioning the internal dependencies of a structural system also implied a [deleted word] harbored the necessary extension into [deleted word] of an urban dialogue. Such a dialogue beginning illegally and in solitude at New York’s Pier 5212 on the Hudson became both clearer and more available to the public on the Paris streets.

Invited by the Bienal13 the site was approximately the upper half of the north walls [deleted word] of 27-29 Rue Beaubourg two modest town houses built in 1700 for Mr + Mrs De Cesseville as what looks like his and her domiciles14. Though these buildings are of little historical importance they remain.

Virtually [deleted word], Amount, the last structures to be torn down in a general Gaullist-Pompidou inspired ‘modernization’ of Les Halles and Plateau Beaubourg15. The project [deleted word] These buildings are brought into full relief by a backdrop of the immense bridge-like structure of the Center Pompidou. To be opened soon as the seat of a half dozen cultural administrations. (five scruffy survivors leaning in a row facing off with a brave-new cob web of culture)16

Despite the odds, through a remarkable set of coincidences this location corresponded with uncanny exactness to project plans for Paris arrived at over a year ago: (a non-u-mental son et lumiére for passers by or a sun and air standard for lodgers)

In short a form that has little to do with any ‘one’ thing.

The shape was a [deleted word] The activity for two plaster dusty weeks was cutting a conical void out of the upper halves of 27-29 Rue Beaubourg so that its base with the north facade was 4m in diameter diminishing in circumference as it passed walls, floors and attic of the adjacent building. The central axis of the opening was set approximately 45° incline from the center of Rue Beaubourg.

notes

For an overview of the Parisian political and socio-cultural context between the late 1960s and early 1970s see: Fumaroli, Marc. 1998. L'État culturel, essai sur une religion moderne. Paris: Editions de Fallois.

The wholesale market at Les Halles managed to establish itself over its many years of operation as a reference point and catalyst for the Parisian community, effectively controlling both the traffic and commercial scales within a single portion of urban fabric. With population growth, improvements in roadways, the advent of new hygiene regulations, and the modernization of commercial activities, the Parisian administration began discussions between 1940 and 1950 about the potential relocation of the markets to a more suitable space in Rungis, on the southern outskirts of Paris. The transfer process was tortuous: on January 6th, 1959, the decision was made, and the move was actually initiated in March 1969 and completed in January 1973, resulting in a functional vacuum.

The decision to relocate and subsequently demolish the markets initiated a proliferation of urban projects by Parisian public authorities, which also affected the Plateau Beaubourg district, an unsanitary block, razed in the 1930s and occupied by a parking lot. After deciding on its future use, an international competition was launched in 1971 by President Pompidou to build a multicultural centre dedicated to modern and contemporary art, flanked by an imposing library.

These notions are the result of the study and subsequent interpretation of documentary material (photographs, correspondence, minutes, bulletins, collections of administrative acts, local and national press articles) found at the Archives de Paris, mainly concerning Les Halles and the development of the area itself.

Despite his training as an architect, Gordon Matta-Clark was a particularly active figure on the American art scene in the 1970s. His experiments in the use of different media and his social-political actions, bordering on the transgressive, led him to join the so-called ‘Anarchitecture’ movement. He was able to pour his artistic charge into buildings, architectural sites and non-functional or neglected spaces of an America that had lost part of its splendour in those years, through alterations and tampering with the architecture laid out.

The work itself consists of a succession of circular cuts connecting the two Parisian buildings, in a mutual exchange between interior and exterior, generating an urban dialogue between the street, the building and the museum site, perfectly appreciable by passers-by.

The design by Victor Baltard, in collaboration with architect Félix Callet (1791-1854), featured four groups of three buildings each, arranged along a central axis and composed of a metal structure with intricate cast iron decorations.

Since new cities sprang up around Paris, the Île-de-France regional development plan called for the RER lines to be extended to the heart of Paris, reducing the journey time through the capital to 12 minutes, and interconnecting this express train with the metro; thus, pavilions 7 to 10 are indicated as the first to be demolished (n.7 intended for the sale of flowers and fruit; n.8 for green, fresh and preserved vegetables; n.9 for tide, freshwater and saltwater fish; n. 10 for wholesale butter, eggs and cheese; n. 11 for oysters; n. 12 for the retail sale of butter, eggs and cheese). The Châtelet-Les Halles RER station was inaugurated on 8 December 1977 by President Valery Giscard d'Estaing (1926-2020).

As reported in an article in Le Monde of June 2nd, 1969 and as witnessed by the reportage “Le dernier frisson des Halles” produced by the Office National de Radiodiffusion Télévision Française in 1969, the pavilions hosted the dancers of the London Festival Ballet company until June 14th, 1969.

Pavilion n.1 hosted the sale of cured meats, pigs, pig products, offal, tripe; n.2 for retail sale of poultry and game; n.3 for beef, veal, mutton; n.4 for wholesale poultry and game; n.5 for wholesale in the morning and retail sale during the day of large vegetables, fruits, greenery, cut flowers, medicinal plants, early vegetables and dried fruits; n.6 same destination as the previous one, but half of which is reserved for the auction sale of the same goods.

Finally, it was decided to keep only one pavilion, number 8, despite the fact that it had an easier structure to disassemble. This pavilion was dismantled in 1972, reassembled at Nogent-sur-Marne, on a plot of land on the edge of the Bois de Vincennes, with some adaptations as the brick panels were not original, and inaugurated in 1977.

Gordon Matta-Clark refers to his site-specific installation "Day's End" at Pier 52 in New York held on August 27th,1975. On that occasion, the artist made a cut in an early 20th century steel truss building, then abandoned; the intention was to convert the construction from an industrial hangar to a temple of light and water. As he did immediately afterwards in Paris, Matta-Clark carried out one of his most complex operations, a series of circular cuts in different parts of the building.

Gordon Matta-Clark is invited by Jean Hubert-Martin (1944-), curator of the Musée National d'Art Moderne, and it is the artist himself who decides to intervene in the peculiar area of Les Halles and, more specifically, on the Plateau Beaubourg (Lee, P. M. 1998. “On the Holes of History: Gordon Matta-Clark's Work in Paris.” October 85 (Summer): 65-89.

In the document numbered D76J-14 found at the Archives de Paris and entitled “Commission du Vieux Paris - Procès-verbal de la séance du lundi 6 novembre 1967 (Supplement au “Bulletin municipale office de la Ville de Paris” du 28 février 1968, n° 42)” the two buildings are referred to as follows: «Rue Beaubourg 27: 16th century building, triple order (one wide bay between two narrow bays). Inside the courtyard, stringed staircase with turned wooden balustrades. Belonged to Madame Lesseville in 1700; Rue Beaubourg 29: 16th-century building, on the pillar at the corner of Rue Brantome. Belonged to Mr Lesseville, Councillor at the Parliament in 1700». Furthermore, in a plan of the Les Halles district dating from February 1968, drawn up by members of the Commission du Vieux Paris and classifying buildings according to their artistic value, the pair of buildings is highlighted in yellow and the legend states «De très bonne qualité» (Very good quality).

The promotion of modernisation to which Matta-Clark refers is related to the artistic, cultural and architectural drive initiated by Georges Pompidou, leader of the Gaullist party and Prime Minister under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle and, subsequently, since June 1969, President of the French Republic. The opportunity in fact presented itself to him in January 1968 when he was commissioned to evaluate the six finalist projects that the Société civile d'études pour l'aménagement des Halles (SEAH) submitted to President de Gaulle as part of the project to renovate the Les Halles district (Hamzeian, B. 2022. Live Centre of Information. De Pompidou à Beaubourg (1968-1971). Barcellona: Actar Publishers).

The clear critical tone of the artist's references to the propagation of this new culture are thus supported not only by these huge cuts, but also by the axis that this periscope intends to draw. His ‘anarchitecture’, his ‘anti-monument’, visually linking the Centre Pompidou to the Eiffel Tower, invites reflection on the demolition actions in ancient contexts and highlights the complete break in continuity between old and new.

Azize Elif Yabacı

Ayla Schiappacasse

Jiayao Jiang Pedro Marroquim Senna

Carlo Francini Vanessa Staccioli Gaia Vannucci