The study proposed was inspired by my conviction that when we discuss architecture and restoration it’s important to reflect on a subject we cannot ignore: the protection and safeguard of so-called ‘endangered’ cultural and architectural heritage. Often we discover that some categories of mobile or immobile ‘riches’ are isolated, derelict or dilapidated due either to local indifference, the economic and social destitution of certain countries, or the powerlessness and possible complacency of international organizations to intervene in specific geographical and cultural areas. These territories are subject of crisis because of social, political and religious reasons, and the heritage is often point of assault and destruction. Communities should work jointly on common goal to support initiative to provide better protection of the cultural heritage. Therefore it is important to involve local authorities in trying to encourage ‘active protection’ and participation. Our objective is the implementation of international cooperation project to enhance the architectural heritage. Complicated situations that still direct the community into destructive scenarios where it is inevitable to think of the reconstruction in response to that need of ‘rimemorativa (remembrance)’, the “Istanza psicologica” theorized by Roberto Pane, which claims to ‘forget’ wounds inflicted in a manner so violent and unexpected. These areas have important conservation problems, all connected with the theme of the ruins; it is one of the conceptual issues of the restoration discipline. The ruin, can only be the subject of essential protection and preservation interventions, far from recoveries for that “unity” and “completeness” image no longer accessible and much less desirable. Any additions and partial additions must meet the criteria of tolerability and eligibility ‘formal’, as well as being limited only to products that need urgent conservation work and suitable protective methods. Finally, the paper concludes with different case studies in order to draw attention to these problems and encourage the drafting of protection and restoration proposals as part of a much desired ‘internationalization’ of the world’s cultural heritage. To sum up, the research aims to involve the international debate on cooperative behaviors in the management and enhancement of the architectural heritage, actions for the formation of a unique historical and cultural identity rather than a cause of conflict, hostility and destruction.

Ma ricostruendo,

torneremo a possedere quello che abbiamo perduto?

Renato Bonelli1

When we discuss architecture and restoration it’s important to reflect on a subject we cannot ignore: the protection and safeguard of so-called ‘endangered’ cultural and architectural heritage.

Even if the international community appears to have finally understood that all cultural heritage belongs to the whole of humanity and therefore needs to be preserved, often we discover that some categories of mobile or immobile ‘riches’ are isolated, derelict or dilapidated due either to local indifference, the economic and social destitution of certain countries, or the powerlessness and possible complacency of international organisations to intervene in specific geographical and cultural and confessional areas.

In the last few decades we have often witnessed situations of negligent disinterest, illegal trafficking of artistic and archaeological assets, and disastrous natural events (earthquakes, floods, tsunamis, etc.). That is not all. Many news agencies promptly report on religious conflicts that spark the destruction of any tangible artefacts not part of the autochthonous culture of that area.

The alarming state of conservation of heritage sites and monumental buildings, in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Nepal, Syria, and Yemen, calls the attention of the international community. These territories are subject of crisis for social, political and religious reasons, and the heritage is often a point of destruction. Communities should work jointly on common goal to support legislative initiatives, protection policies, enhancement of the management processes, to provide a better protection of the cultural heritage and to ‘value’ the places.

Therefore it is important to sensibilise and involve local authorities in trying to encourage ‘active protection’ and participation. Our objective is the implementation of an international cooperation project to enhance the architectural heritage. Complicated situations that still direct the community into destructive scenarios where it is inevitable to think of the reconstruction in response to that need of ‘rimemorativa’ (remembrance)’ which claims to ‘forget’ wounds inflicted in a manner so violent and unexpected.

These areas have important conservation problems, all connected with the theme of the ruins; it is one of the conceptual issues of the restoration discipline. The ruin, can only be the subject of essential protection and preservation interventions, far from recoveries for that ‘unity’ and ‘completeness’ image no longer accessible and much less desirable. Any additions and partial additions must meet criteria of ‘minimal intervention’, tolerability and eligibility ‘formal’, as well as being limited only to products that need urgent conservation work.

Numerous documents and various organizations international, governmental and nongovernmental, are devoting themselves, in recent years, to the defense of such heritage through the definition of recommendations and operational proposals ranging from conflict prevention to the protection of monuments during hostilities to restoration2.

The essay presents some case studies in order to draw attention to these problems and encourage the drafting of protection and restoration proposals as part of a much desired ‘internationalisation’ of the world’s cultural heritage.

Many institutions, national and international, could join together and agree on this line of action (Iccrom, Icomos, Icom3, Ifla, Ica and Unesco); out of all these agencies, it was above all Unesco which, at the end of its general conference held in October 2003, adopted a declaration condemning the international destruction of cultural heritage4. This declaration fully respects current legal agreements and is an important point of reference for the international juridical protection of cultural heritage during wartime and periods of peace. However, the dramatic events of the past few years and latest international events require a more up-to-date proposal to encourage the participation of all the communities considered by the consolidated international collectivity as socially and culturally ‘difficult’. Most recently, the United Nations Security Council, by resolution 2347 of March 24, 20175, have supported precise positions by adopting acts that condemn the intentional destruction of cultural property without territorial limitations and for any kind of traumatic event.

The international Unesco conference held in Warsaw, from 6 to 8 May 2018, wanted with the Warsaw Recommendation on Recovery and Reconstruction of Cultural Heritage “to summarize previous discussions and experiences regarding the recovery and reconstruction of Unesco World Heritage sites, and attempt to develop the most appropriate, universal guidelines for moving forward with properties of exceptional value at the time of destruction, notably for historic urban areas6”. The participants deeply concerned by the growing impact of armed conflicts and disasters on important cultural and natural heritage places, have identified eight key points and defined a set of principles: Terminology-recovery/reconstruction, Values-authenticity, Conservation doctrine-cultural landscapes, Communities, Allowing time for reflection, Resilience, Capacities and sustainability, Memory and reconciliation, Documentation and inventories, Governance, Planning-Historic Urban Landscape, Education and awareness raising, considering, moreover, that the recovery of the cultural heritage lost or damaged as a result of armed conflict offers unique opportunities,

(...) promote dialogue and lay the ground for reconciliation among all components of society, particularly in areas characterized by a strong cultural diversity and/or hosting important numbers of refugees and/or internally displaced people, which will lead to new approaches to recovery and reconstruction in the future7.

Faced with these devastating, complex scenarios, we ‘initially’ and inevitably focus on complete reconstruction so as to satisfy our psychological, i.e., “rememorative”8 need to try and ‘forget’ violent, abruptly inflicted wounds. In fact, when these circumstances occur, civilized society tends to want to implement programmes to recompose and restore the destroyed assets. Relevant examples are the initiatives currently underway in war zones or areas that have suffered catastrophic events.

After a natural disaster or destructive war episode communities instinctively want to ‘heal’ the sudden interruption separating them from their past. They try to rapidly reactivate “continuity with their past” by “rebuilding in situ”9 (fig. 1), since they consider this the only way to regain their historical identity; very, very seldom do they adopt reconstruction mechanisms focusing on modification, i.e., on “guidelines of change10”.

Sites affected by social and political controversies, i.e., places rife with ancestral issues such as ethnic conflicts, religious discriminations and insults are another important issue for architecture and archaeology. We are all familiar with the expropriation, destruction or trafficking of cultural archaeological assets in the Maghreb, Syria, Egypt and Iraq; these actions are the tangible result of an ideology imposed by regimes that unscrupulously exploit archaeology. Tangible proof comes from the activities of radical Islamist movements that often focus on artistic heritage and violate any tangible asset not part of the culture of that specific area. Examples include: the looting of the museum in Mosul (2003 and 2015); the fire in the library of the oldest university in the Maghreb located in Timbuktu (Mali, January 2013) (fig. 2)11; the destruction of the mosque of the prophet Jonah (Nabi Yunis) in Iraq (2014); five of the six world heritage sites in Syria, including the ancient city of Palmyra12 and the old districts of Aleppo; the National collection of the Bardo, in Tunis, after the terrorist event (March 18, 2015) maintained, as a testimony, “the signs of the attack” as a place of memory of a tragic moment for the community13; the demolition of the Bamiyan Buddhas (Afghanistan) in 2001; and the attack in Jehanabad (Pakistan) in 2007 where a similar Buddhist iconography suffered the destructive anthropic actions (fig. 3).

On September 27-30, 2017, Unesco, together with the Government of Afghanistan and Tokyo University of the Arts, convened a technical meeting followed by a public Symposium in Tokyo entitled The Future of the Bamiyan Buddha Statues: Technical Considerations and Potential Effects on Authenticity and Outstanding Universal Value. These events provided an opportunity to discuss the reconstruction of the Buddha statues, which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. These forums were also the occasion to examine, discuss, and assess the possibility of reconstruction of one or more of the Buddha statues at the Bamiyan World Heritage property according to different proposals presented by international experts: how can reconstructed heritage using non-original materials be considered to retain authenticity?14.

Furthermore, we should not forget the disastrous events caused by wars and political attacks intended to wipe out the identity and historical memory of the populations involved. This will be followed by illustrating some of the most significant examples of many reconstructions, including the different solutions adopted: from the recovery of old buildings to brand new constructions, from simplified reconstruction to reintegration.

The strategic bombing of the island of Malta during the Second World War (1940-1942) destroyed many of its historical buildings, including the Royal Opera House in Valletta, also known as the Royal Theatre15. Destroyed in 1942, many reconstruction proposals have been presented over the years16, including a project of Renzo Piano who decided not to recompose the fragments – now part of the image of the city – but by reinterpreting the area of the abandoned ruin as a huge, open-air theatre where the nineteenth-century remains of the columns merge with the steel pylons of a system of transparent screens that are vertically lowered during performances to close off the theatre and create the stage (fig. 4).

Piano explains that his idea merges:

(...) past and present, history and modernity, in a town like Valletta and on the remains of a building dear to many people [...] Destroying the remains and replacing their function would have been the real sacrilege. I believe, instead, that by preserving the ruins, giving them a role and dignity, and by adding mechanical elements and modern stage machines [...] we have done something extraordinary, a magical gesture17.

In this case the ruin becomes a monument not only to itself, testifying to violence, for example Hiroshima in Japan (August 6, 1945), but also a “political act of condemnation18”; the surviving piece of evidence is frozen in time as an everlasting memory of the event so that it cannot be easily forgotten should the ruin be reconstructed. The same idea inspired the imposing, temporary installation, The Stairs, inaugurated on May 16, 2016 in Rotterdam, a city extensively destroyed during the Second World War (fig. 5)19 .

The installation was erected to recall the bombing in 1940 and commemorate the 75 years during which the city has been rebuilt (1946)20 thanks to a reconstruction plan of the city centre developed in line with the Master Town Planning Scheme envisaged for the future city.

How can we not be reminded of the current crisis situation: the war in Ukraine and destruction of the cities, has opened a new debate on reconstruction. The transformation process should be led by Ukrainian actors and Ukrainian institutions and it should be informed by a deep knowledge and experiential grounding in Ukrainian culture, society and heritage with attention to cities, architecture, art, culture and psychological trauma21; a reconstruction can usefully be informed by comparisons with other places and contexts which have undergone –or are still undergoing– processes of ruination and renewal22.

The destruction caused by natural events is no less challenging. Italy is a high seismic risk country with a complex, vulnerable and compromised hydrogeological system. There have been several positive experiences; one example is the earthquake in Friuli where the community participated and actively rebuilt its historical, cultural and social identity. Others have been negative and debatable, i.e., the earthquakes in Campania, Sicily, Umbria, not to mention the ongoing situation in L’Aquila, in Emilia Romagna and the last tragedy of 24 August 2016 between Umbria and Marche.

Italy has very limited reconstruction options. In fact, previous choices show they vary between reconstruction, in situ, or buildings in new settlements, far away from the urban nucleus. However both solutions appear to ignore the need to understand the situation on the ground. Instead this premise should be the strong, starting point to promote different rebuilding approaches on a ‘case-by-case’ basis depending on the cultural identity of each specific site. Any approach must also consider the individual needs of the community so as to safeguard and protect memory as well as the spirit of the site.

After most of these events communities hit by earthquakes tend to want to remain and rebuild in the same place: this happened in Friuli, after the earthquake in 1976, when the community made a conscious decision to reconstruct the city’s lost identity with all its historical meaning and memories. In Gemona the choice was based on the principle “as it was, where it was”, but with more of a humanist rather than architectural approach; this solution reassured the populations that did not want to feel uprooted. On that occasion the town planner Giovanni Pietro Nimis essentially focused on an independent political project. His approach was further enhanced by the fact that Friuli is a peripheral, independent region with a special statute, and that the citizens actively participated in its reconstruction, sharing directives and choices to achieve a common goal.

Shifting a community to a neighbouring area and building in a different territory sparks further disorientation and changes to the inhabitants’ habits, plus an inevitable loss of cultural identity and sense of belonging to a place. Fully aware of the difficulties involved with moving out of the urban nucleus, in Pescomaggiore the inhabitants of the small late medieval municipality at the foot of the Gran Sasso mountain decided to implement an ambitious programme after the earthquake on April 6, 2009 that destroyed most of the houses. They took part in an innovative, participative project and chose to self-finance and self-built an eco-village adjacent to the urban nucleus: the so-called EVA (Self-built Eco Village) with housing units that had minimum environmental impact and respected antiseismic regulations23.

After the earthquake on November 23, 1980 in Irpinia a difficult reconstruction based primarily on safety and prevention ultimately altered the typological and morphological relationships of the towns, disrupted their fabrics and created anonymous ‘places’ with which the community is unable to identify.

Then there is the case of Salemi in Sicily (Belice Valley) where since 1982 the old town centre is still being rebuilt after the earthquake in 1968. The exemplary renovation of Piazza Alicia is based on a design by Roberto Collovà, Álvaro Siza and Orazio Saluci; the architects have tried to ‘reconvert’ the ruins in order to ‘re-establish’ the city (fig. 6).

The design does not involve the reconstruction of the Mother Church, but turns the dilapidated nave of the destroyed church into a new, renovated space, i.e., into a new square bordered by the ruins of the apse and the ‘footprints’ of the columns. The square is also embellished by urban furniture made from leftover elements.

After the 1997 earthquake in Umbria and Marche a new institutional model was tested right from the start. It involved nominating three commissioners: two regional Presidents, who focused on planning, and the General Director of Cultural Heritage who concentrated on the historical and artistic heritage. Instead in 2009, immediately after the earthquake in the Abruzzi, a political decision was taken to build nineteen new settlements, the so-called ‘new towns’, while the reconstruction of the old town centre was initiated only a few years later.

Most of these interventions, proposals and considerations were provided exclusively by the town planning sector which tends to establish categories of catastrophes and interventions without considering the data and ‘values’ of the places in question. This often creates an insurmountable gap between “historical method” and “Hermeneutic method”24, processes that cannot find a point of contact. Likewise, it’s impossible to make the nostalgic supporters of reconstruction “as it was, where it was” dialogue productively with those who enthusiastically defend “new at all costs”; on the contrary, this sterile debate has led either to unsuccessful projects or missed opportunities.

All this undoubtedly means that designing is complex: it must succeed in sparking mediation between extreme positions, trying to acknowledge the different ‘values’ of places and architectures and identifying multiple, versatile, ‘suitable’ and ad hoc solutions for every post-traumatic situation, as well as representative, identity-oriented proposals for the entire urban system.

These projects have to be able to evolve and adapt to different contexts, above all they must be capable of ‘preserving’ the bond between citizens and their city so as not to lose the sense of community that characterises urban centres; they must neither disrupt the complex system and nature of the city, nor try to find opportunities to rebuild something that is irremediably lost.

In a document dated June 20, 2012, the National Association of Historical and Artistic Centres defined the objectives for the reconstruction of old town centres in Emilia Romagna. These objectives are to “safeguard the meaningful relationship and identity of places and layouts, starting with collective spaces, and respect their function and morphology, even when part of the urban fabric has to be demolished and rebuilt in order to guarantee the safety of the inhabitants. Reconstruction that respects the meaning of public space is a priority for the revival of social life and a tool to accelerate work on private heritage25”.

All the aforesaid examples are certainly very different, complex experiences that have almost never taken into consideration the needs and characteristics of the places in question; they have focused more on fixed reference models rather than on the uniqueness of historical and environmental values or on the multifaceted history and culture of Italy’s territories and historical centres.

Eight actions, based on historical knowledge, are all that is needed to reconnect the fragments to the rest of the city system: repair the lacerations in the urban and/or architectural organism; ‘stitch’ together pieces of the frayed urban fabric; reinterpret the ‘empty spaces’ without “destroying structural values which are often the key qualities of so-called ‘basic construction’26”; allude to the losses without necessarily duplicating the city of the past; reinsert the remains in a compatible context. Simply put, the aim is to rewrite the past, but with a contemporary slant, and to look towards the future without stylistic tricks or reproductions.

It’s crucial to continue to design, to try and use reconstruction to maintain the history, art and culture of old town centres. On this issue Paolo Portoghesi said in an interview:

We urgently need to design. Structural rigidity is not enough: we need to work together so that the characteristics of municipalities destroyed by earthquakes are as similar as possible to their former characteristics27.

We remember, also, the Gorkha Earthquake (April 12, 2015), in Nepal, where thousands of houses and temples were destroyed, with entire villages flattened, especially those near the epicenter. Unesco and the National Society for Earthquake-Nepal (NSET) jointly organized the 19th Earthquake Safety Day symposium Lessons from the Gorkha Earthquake: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Safeguarding, Re-strengthening and Reconstruction of Cultural Heritage on January 26, 2017. The main issues raised by participants, ranged from the lack of periodic maintenance of heritage structures, to the importance of documentation and community engagement. Other topics included the seismic strengthening of heritage structures and the need of following conservation guidelines while respecting traditional building material and techniques28.

Fires are no less important or problematic, whether they be accidental or started by man either during wars or in times of peace. These are tragic events for our cultural heritage and long debates and discussions often continue at length during their reconstruction. For example, several Italian theatres destroyed chiefly by malicious fires and rebuilt exactly as they were. One such theatre is the Petruzzelli in Bari ruined by a fire in 1991 and rebuilt in its original facies in 2009. Another is the Fenice Theatre in Venice which, after a disastrous fire in 1996, was rebuilt à l’identique in December 200329.

Or, more recently, the Glasgow School of Art devastated by a fire on May 23, 2014 and currently part of an accurate rebuilding project, especially as concerns the furnishings and decorations of the Mackintosh Library (1897-1899). The building, considered to be Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterpiece, was restored and reopened in 2019, with the enlargement of the building on Steven Holl’s design. But, five years later, on June 15, 2018, a second blaze took hold of the school’s Mackintosh building, also causing major damage to neighbouring properties such as the O2 ABC venue30.

The reaction of the international architectural community to the episode was strong. The immediate debate over the building’s fate pitted the opinions of scholars and architects against each other, culminating in the decision to rebuild the ‘Mack’ announced by the school’s director, Tom Inns. The course to be taken for the building’s future was not a foregone conclusion: proposals to demolish in favor of a new building and those to construct one while retaining the historic façade were weighed31.

What has re-emerged in the above-mentioned cases is “a sort of ‘retrospective trend’”32 to revive what is lost. Instead reconstruction could take place by establishing a “free formative process, the result of which would be nothing but a new building” duplicating its “spatial, but not formal data33”.

And how can we forget the Notre Dame Cathedral fire on April 15, 2019, a very complex topic that deserves an in-depth study not a few lines but of an extended and articulated debate on the discipline of restoration which we defer to another occasion34.

Italy also has to face other ‘evergreen’ destructive activities such as the theft and looting of artworks, vandalism and terrorist attacks of 1993, the destructive 30th anniversary of which marks this year: how can we forget the bombs against the churches of St. John Lateran, St. George in Velabro in Rome and the Tower of the Georgofili Academy in Florence.

During the night of July 27-28, 1993 the mafia launched a terrorist attack against several buildings: the PAC, in Milan (Pavilion of Contemporary Art in Via Palestro) and two monumental buildings in Rome: the Loggia of Benedictions in St. John Lateran, and the Church of St. George in Velabro (fig. 7).

The next day the Superintendency for Environmental and Architectural Heritage of Rome began to meticulously collect all the rubble and debris around St. George in Velabro. Immediately afterwards it used the funds allocated by the Ministry for Civil Protection pursuant to the Decree issued by the Prime Minister’s Office and disbursed by the Prefecture of Rome to begin the long, challenging reconstruction of the thirteenth-century portico, almost completely destroyed by the blast. Together with all the political parties it tried to heal this serious wound inflicted not only on the State, but also on Italy’s historical, artistic and architectural heritage. Another approach was adopted for the reconstruction of the Georgofili Tower in Florence (May 27, 1993): a decision was taken to leave a visible sign of the event. In fact, the old and reconstructed parts were treated differently and left divided by the fracture caused by the bombing35.

Pursuant to this event a lively, multifaceted debate on the problems involving reconstruction after traumatic events began to appear in the pages of specialised periodicals. Experts, politicians and scholars all tried to suggest the right solution to one of the key conceptual issues of restoration: when something is destroyed should we preserve or rebuild? Obviously, there were multiple answers: restoration, a ‘critical’ approach, conservation of the ruins, and a ‘modern’ intervention capable of dialoguing with the remains. The latter based on the theoretical and methodological approach of the current culture of conservation.

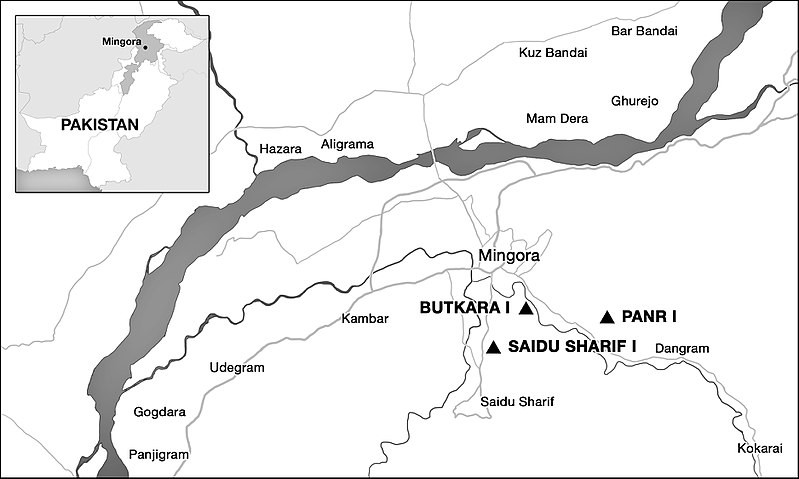

Another alarming event is the rejection and abandonment of archaeological sites not linked to the majority culture, or the occupation of these areas as the training camps of terrorist armies: in Pakistan, Swat Valley, Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq.

For example, several Buddhist-style architectures in the Swat Valley in Pakistan, less well-known artefacts of the artistic production of the Grand Gandhara documented in Afghanistan. These archaeological areas are exposed not only to the weather (earthquakes, floods, monsoons), but also to the actions of man (fires, explosions, abandonment and looting). These actions threaten their physical integrity and compromise their features, meanings and ‘value’; in short, we risk losing this heritage forever. Most of these deliberately forgotten ruins that have survived the ravages of time are often considered artefacts linked to the landscape, elements bearing witness to a heritage that still exists but is waiting to be ‘re-acknowledged’ and enhanced.

The international community, however, appears disinterested and is careful not to talk about these sites or communities isolated and left alone to deal with the problems involving what is left after the destruction of their unique, inimitable heritage. Notwithstanding their current isolation, in the past generations of Italian scholars and archaeologists have worked together to uncover and discover some of these settlements; for example, the work performed in Saidu Sharīf by the Italian Archaeological Mission from the 1950 to 2007, when political events forced it to abandon the project, but now again active (fig. 8)36.

These areas have serious conservation problems, all linked to their ruins37. This is one of the key conceptual issues of the discipline of restoration, i.e., abandoned sites where the “rudero (ruin)”38 inevitably establishes an indivisible relationship with the natural environment. The very few artefacts that have survived the ravages of time represent elements connected to the landscape; they are the remains of a heritage that still exists but has to be ‘re-acknowledged’ and enhanced.

The formal incompleteness of the ruin and its strong link with the surrounding environment means that its material nature can only be defended and maintained; these are ‘basic’ actions and do not represent a desire to implement a restoration project focused only on accomplishing a ‘united’ and ‘complete’ image that is no longer achievable and much less desirable.

An analysis of the material decay would make it possible to adopt a ‘cautious’ operational strategy, i.e., the implementation of interventions tailored to the needs of each artefact so as to prolong the life of the ruin. In other words, actions to protect pre-existing elements. Measures should involve: cleaning, control of the decay and infesting vegetation, construction of structural facilities, consolidation and reintegration of missing parts, and the protection of wall tops and surfaces. The current state of these ruins makes it inevitable and urgent that we proceed by adopting ‘minimum interventions’ and compatible operations. Any additions and partial completion must satisfy criteria of physical and chemical tolerability as well as be ‘formally’ admissible; they must also be limited to those artefacts requiring urgent conservative interventions and suitable protective measures.

After a preliminary study phase a protection and enhancement plan involving local populations and workers would need to be drafted for the site in question. Local administrators must be sensitised and involved in ‘active protection’, even when the cultural and political premises are in contrast with the past history of the site. In order for protection and enhancement plans to be drafted for the site, the scientific community should show greater interest in these unquestionable ‘values’ of history and places (fig. 9).

Given the destruction and looting in Tunisia39 (fig. 10), Libya and Egypt, part of this approach involves the democratisation processes triggered by political and social changes, i.e., the so-called ‘Arab springs’, which took place in several societies in the Middle East. This problem chiefly involves archaeological sites in these countries where inestimable historical cultures have either been destroyed or wiped out.

Numerous archaeological sites and architectures have either been abandoned or are crumbling to pieces; these conditions are often caused by disastrous situations in neighbouring countries, but also by disinterest and lack of appreciation by the international cultural world and the countries where these artefacts are located. In fact, we often witness a certain lack of involvement and ‘controlled’ silence by the international community vis-à-vis certain situations and communities isolated and left alone to deal with these problems. Compared to their current isolation, in the past these geographical areas were visited by generations of Italian scholars who collaborated to explore, discover and restore a heritage acknowledged as unique by the international community.

Palmyra is one case in point. Although most of the city had already been destroyed in recent years, in the last time it has come into the international spotlight because further destruction has been inflicted on its artefacts: the proscenium of the Roman Theatre and the Tetrapylon, the grand colonnade considered a world heritage site by Unesco40. However, despite such a despicable situation, this supranational organisation is unable to implement any preventive measures, much less diplomatic initiatives or sensitisation programmes, “concrete actions against heinous crimes such as the destruction of the history and artefacts of ancient civilisations, often linked to the illegal trafficking of cultural assets used to finance terrorism41”.

The Technical Meeting on the Recovery of the World Heritage Site of Palmyra took place on December 18, 2019 at Unesco’s Headquarters, with the aim of reflecting on, and discussing the recovery of the archaeological site, as a World Heritage property, requesting to limit restoration works to first aid interventions until the security situation has improved, therefore allowing for detailed studies and extensive fieldwork, as well as discussions on defining optimal approaches42.

All these very different kinds of problems involve the protection and safeguarding of all tangible and intangible cultural heritage and intellectual property, documentary, archaeological, artistic and musical. In fact, as part of our intangible cultural heritage, music is often either forgotten or handed down only from generation to generation.

On October 17, 2003, in its closing statements the Paris Convention for the Safeguard of immaterial cultural heritage focused on the protection of the so-called “immaterial cultural heritage of the community43”. More recently, the Québec Declaration (2008) on the spirit of place defined intangible heritage as “memories, narratives, written documents, festivals, commemorations, rituals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, colours, odours, etc.”44 and accordingly required them to be safeguarded.

One example of a musical heritage that needs to be safeguarded is of Tunisia, specifically the museum of musical instruments created by Baron Rodolphe d’Erlanger (1872-1932), researcher, pioneer and patron of traditional Arab music. In the early nineteenth century he turned his own home in Sidi Bou Said, a town in northern Tunisia, into a centre for musical education and execution.

Likewise, but in the literary field, the situation is becoming increasingly critical in Yemen. In fact, its cultural heritage is now at risk.

This is why we must support the efforts of the writer Arwa Othman, founder of the bayt al-mauruth al-shaabi (the house of popular traditions). The house has a collection of photographs, papers and documents referring to nineteenth-century Yemen, as well as musical instruments and all sorts of objects and knick-knacks. Today most of this heritage has been destroyed by fundamentalists, but some of it has been hidden away in the houses of those loyal to the institution, in the hope that better days will come in the future and a new house be found in which to display the objects.

Instead on a more positive note we should mention the library in Fez, one of the oldest in the world, founded in 859 A.D. by Fatima Al-Fihri; it has approximately 4.000 precious volumes including treatises of medicine in verse, books on astronomy, and manuscripts45. In the last four years al-Qarawiyyin has been restored by Aziza Chaouni, a socially committed architect who has fought to allow access to the library by a more diversified public.

The post-World War II season led to the emergence of the modern debate on architectural restoration and awareness of the identity value of monuments and historic centres severely damaged during the world conflict, though, for example, the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (1954). Cultural heritage has increasingly been regarded as a global asset, leading to the emergence of national and international associations, institutions and entities active on preservation issues. Today, in different ways and at different scales, restoration and historical sensitivity play a constant social role in conflict-ridden territories and in sites and cities subjected to terrorist attacks in various ways. This phenomenon is embodied in the affirmation of local identity and the attempt to safeguard, document and intervene in the effects of these events in crisis areas.

In territories undergoing recovery, in fact, the heritage of history, to whatever phase it belongs, must be perceived as a valuable asset for future social and economic development, both for the possibility of attracting investment – for specialized, cultural and sustainable tourism purposes – and for the setting up of new productive activities. It would be necessary, therefore, to sensibilize and involve the local administrative apparatus in ‘active protection’, even when cultural and political assumptions come into conflict with the past of places. Moreover, the scientific debate focuses on sustainable reuse of historical settlements and on the stratigraphic overlapping “ancient-new”.

Hopefully it will be possible to spark an important debate and discussion on intervention criteria and methods during times of crisis as well as share the different perspectives, methodologies and practices used to not only tackle difficult situations, but also ensure proper conservation of our Heritage and increase reciprocal respect and dialogue between all interested parties and actors, however diverse they may be.

The goal of this paper was to not only draw attention to the problems involving the protection of cultural heritage in extreme situations, but also encourage a commitment by international organisations to cooperate in the management and enhancement of architectural heritage and create a single, joint, cultural and historical identity rather one which causes conflict, hostility and destruction.

notes

Bonelli, Renato. Architettura e restauro. 1959. Venezia: Neri Pozza, 36.

Leturcq, Jean-Gabriel, and Jean-Loup Samaan. 2018. The Soldier and the Curator. The Challenges of Defending Cultural Property in Conflict Areas. Abu Dhabi (United Arab Emirates): Emirates Diplomatic Academy.

On October 10, 2016, in Rome, ICOM-Italy published ICOM Italy Decalogue on Interventions in Emergencies Following Natural Disasters to raise awareness of prevention, to activate states of emergency in times of crisis, as well as to define interventions for affected structures and cultural property.

Unesco. 2003. Convenzione per la salvaguardia del patrimonio culturale immateriale. Parigi: Unesco, 17 ottobre.

Protecting of Cultural Heritage in Conflict Areas-Approval by the United Nations Security Council, Resolution 2347, submitted by France and Italy; Niglio, Olimpia. 2017. “Patrimonio culturale e conflitti armati. La Dichiarazione di Abu Dhabi”. Dialoghi Mediterranei 25, May 1, 2017. http://www.istitutoeuroarabo.it/DM/patrimonio-culturale-e-conflitti-armati-la-dichiarazione-di-abu-dhabi/.

Unesco. 2018. Warsaw Recommendation on Recovery and Reconstruction of Cultural Heritage. Warsaw: Unesco, May 8, 2018. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1826/.

Ivi, 2.

Pane, Roberto. s.d. “Urbanistica Architettura Restauro nell’attuale istanza psicologica”. Rivista di Psicologia Analitica. Accessed May 3, 2023. http://www.rivistapsicologianalitica.it.

Musolino, Monica. 2013. “[Distruzione, ricostruzione, memoria]. La catastrofe come mito fondativo ed evento costitutivo di un nuovo ordine temporale”. Cambio 11, no. 6 (December): 237-48, doi: 10.1400/218599.

Ivi, 237.

Unesco has initiated a restoration and building programme in Timbuktu; this project is co-funded by the Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, which provides technical support and salaries for local workers.

Reports also mention the destruction of the proscenium of the Roman Theater and the Tetrapilus of the archaeological site. Mattioli, Massimo. 2017. “Chiudiamo l’Unesco. L’Isis devasta il teatro di Palmira, e l’organismo assiste imbelle”. Artribune, January 10, 2017. Accessed May 1, 2017. http://www.artribune.com.

Gallico, Sonia, and Maria Grazia Turco. 2016-2017. “Tunisia: il restauro dopo la ‘Rivoluzione’. Considerazioni su alcune esperienze”. Confronti 8-10, January 2016-June 2017: 142-52.

Unesco. 2017. The Future of the Bamiyan Buddha Statues: Technical Considerations and Potential Effects on Authenticity and Outstanding Universal Value. October 11, 2017. Accessed July 8, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1733; Masanori, Nagaoka. 2020. The Future of the Bamiyan Buddha Statues: heritage reconstruction in theory and practice. Unesco Office in Kabul, Berlin: Springer.

The theater, built in 1866, was designed by english architect Edward Middleton Barry; in 1873 its interior was extensively damaged by fire but was restored in 1877.

Mention should also be made of the projects of: Rossi Zavellini, R. S. Nickson, M. A. Perret, A. Mc Donald (1955); A. Bezzina-K. Cole-A. Torpiano, W. Soler, J. Camilleri-C. Grech, R. England-Burton-Koralek (1992); R. England (1998, 2006-2008).

Mifsud, Lyanne. 2012. “Riflettere sulla nostalgia delle città”. Domus, June 27, 2012. Accessed January 20, 2017. http://www.domusweb.it.

Matthiae, Paolo. 2015. Distruzioni, saccheggi e rinascite. Gli attacchi del patrimonio artistico dall’antichità all’Isis. Milano: BibliotecaElecta, 42.

It is a 180-step staircase made of scaffolding that, from the station, leads visitors 29 meters up to the roof of the Groot Handelsgebouw, a landmark building of the city’s postwar reconstruction, where a panoramic observation platform offers views of the entire city.

The work was commissioned from MVRDV Studio.

Dyak, Sofia. 2023. “From War into the Future: Historical Legacies and Questions for Postwar Reconstruction in Ukraine”. Architectural Histories 11 (1). doi: https://doi.org/10.16995/ah.9805.

Italy will also be present: the president of Maxxi Museum, Alessandro Giuli, and the president of the Milan Triennale, Stefano Boeri, will be in Odessa, on September 6-7, 2023, for a meeting with local authorities and a reconnaissance of the destroyed sites, starting with the Cathedral of the Transfiguration.

The design by architects Paolo Robazza and Fabrizio Savini of BAG studio, with the support of bio-architecture expert Caled Murray Burdeau, consists of the use of wooden structures and thatch bale infill to create buildings that fit into the agricultural landscape; this is followed by the use of voltaic systems and heating with wood stoves.

Bertin, Mattia. 2013. “La città di soglia, uno strumento per unificare l’analisi delle esperienze di rigenerazione urbana”. In La ricostruzione dopo una catastrofe: da spazio in attesa a spazio pubblico, edited by Valter Fabietti, Carmela Giannino, Marichela Sepe, 22-26: 24. Roma: INU Edizioni.

ANCSA: salviamo le città e il territorio storico, punto 4. Accessed January 20, 2017. http://www.ancsa.org/it/index.html, June 20, 2012.

Miarelli Mariani, Gaetano. 1993. Centri storici note sul tema. Roma: Bonsignori Editore, 94.

Picardi, Andrea. 2016. “Come ricostruire dopo il terremoto. Parla l’architetto Portoghesi”. f. Formiche. Analisi commenti e scenari. November 2, 2016. Accessed January 28, 2022. http://formiche.net/2016/11/02/terremoto-ricostruzione-portoghesi.

Protecting Cultural Heritage: Lessons from the Gorkha Earthquake. February 2, 2017. Accessed June 3, 2023. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/protecting-cultural-heritage-lessons-gorkha-earthquake.

Sette, Maria Piera. 1996. “Venezia, La Fenice: i fatti, gli atti ufficiali, le opinioni”. 'ANANKE 13: 32.

“Glasgow art school fire: Sturgeon says blaze is ‘heartbreaking’”. BBC News, June 16, 2018; “Glasgow School of Art: A timeline of two fires”. BBC News, January 25, 2022. Accessed June 2, 2023. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-glasgow-west-44507189.

Meterc, Silvia. 2018. “Glasgow School of Art di Mackintosh: una strategia per la ricostruzione”. Artribune, July 26, 2018. Accessed June 28, 2023. https://www.artribune.com/progettazione/architettura/2018/07/glasgow-school-of-art-ricostruzione.

Miarelli Mariani, Gaetano. 1996. Op. cit., 34.

Ibid.

The reopening of Notre-Dame is announced for the 8th December 2024; the supervision of the restoration is entrusted to the architect Philippe Villeneuve: the general principle is to rebuild the cathedral identically, including the spire. The redevelopment of the surroundings area is being carried out by the team of the Belgian architect and landscape architect Bas Smets, project involving of green spaces.

AA. VV. 2002. “La chiesa di San Giorgio in Velabro a Roma. Storia, documenti, testimonianze del restauro dopo l’attentato del luglio 1993”. Bollettino d’Arte.

Present director is Luca Maria Olivieri.

Cimbolli Spagnesi, Piero. 2013. Lungo il fiume Swāt. Scritti di architettura buddhista antica. Roma: Aracne; Turco, Maria Grazia. 2014. Complessi buddhistici nella Valle dello Swāt. L’area sacra di Tokar-Dara 1. Tipologie, tecniche costruttive, problemi di conservazione. Roma: Aracne.

Brandi, Cesare. 1977. Teoria del restauro. Torino: Piccola Biblioteca Einaudi, 42.

Gallico, Sonia, and Maria Grazia Turco. 2015. “Restauri in Tunisia. Dal Protettorato alla ‘primavera araba’”. Materiali e Strutture. Problemi di conservazione 7, IV: 73-94.

Recommendations of the Technical Meeting on the Recovery of the World Heritage Site of Palmyra. Friday, July 17, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2133.

Franceschini, Dario. 2017. Devastazione Palmira crimine odioso, January 8, 2017. https://www.beniculturali.it. Accessed March 19, 2017.

Recommendations of the Technical Meeting on the Recovery of the World Heritage Site of Palmyra. July 17, 2020. Accessed June 3, 2023. https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/2133.

Convenzione per la salvaguardia del patrimonio culturale immateriale. October 17, 2003, Paris: 1. Accessed March 10, 2016. https://www.unesco.beniculturali.it.

Québec Declaration on the preservation of the spirit of place. Québec, Canada, October 4, 2008: 3. Accessed March 20, 2017. http://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-646-2.pdf.

Among the texts: a 9th century copy of the Quran, written in Kufic characters, and one of the Gospel of Matthew, dating from the 12th century.

Luigiemanuele Amabile Alberto Calderoni

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Lorenzo Mingardi (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Edited by: Luca Cardani (Politecnico di Milano), Federica Causarano (IUAV Università di Venezia), Francesca Giudetti (Politecnico di Milano), Luciana Macaluso (Università degli Studi di Palermo) and Martina Meulli (Sapienza Università di Roma)

Edited by: Elisa Boeri, Elena Fioretto and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)