Following the Second World War, numerous European cities grappled with the challenging task of reconstruction. Despite the transformative impact of these reconstruction projects on the urban landscape of Europe, the historiography of urbanism tends to acknowledge them only minorly, often reducing them to the mere creation of new housing developments or city centres.

However, the reconstruction plans for European cities went beyond surface-level planning of neighbourhoods or central city areas. They were intricately connected to specific instances of urbicide and involved elaborate negotiations with pre-existing social, legal, economic, technical and morphological conditions, as well as with prevailing agencies.

Focusing on the cities of Milan, Rotterdam and Warsaw, this article argues that, due to their charged relationship with the existing fabric, urban reconstruction projects appear as alternative approaches to post-war urbanism. They emerge as exemplars of a ‘situated modern urbanism’ distinct from their counterparts, as they establish a modern urbanistic approach grounded in a highly nuanced understanding of the dimensions of time and agency.

The Second World War caused an annihilation of cities across the European continent. While the initial appearance of the debris in various cities might have seemed similar, the actual manifestations of urbicide varied significantly. The Italian city of Milan, for instance, after the Second World War, was a true ‘scattered city’ as regards its built fabric and possibly even more as regards its social tissue. To counter the Fascist regime, the Allied Forces primarily employed psychological warfare as their key strategy. Creating psychological trauma with the Milanese rather than the total physical destruction of the city by so-called ‘terror bombing’ was the approach employed by the British Royal Air Force between 1940 and 19451. It consisted of minor but recurrent attacks, which generated significant psychological and moral impact, anxiety and panic. The effect on Milanese morale was enormous, leading some observers to conclude that “The Italian psychology was unsuitable for war2”.

The eradication of morale was paired with a ‘scattered destruction’ of various parts of the built environment. Small pieces of urban fabric were destroyed all over the city, turning Milan into a porous urban entity full of cavities and voids. The scattered pattern of destruction was not only the result of the dispersed character of the ‘terror bombing’ strategy but also of the material qualities of the city. The modern areas with wide streets (some more than 8-9 metres) and the typical use of bricks and reinforced concrete were not affected as much by the bombings and the resulting fire3. The older neighbourhoods with their wooden buildings were easily destroyed by fire:

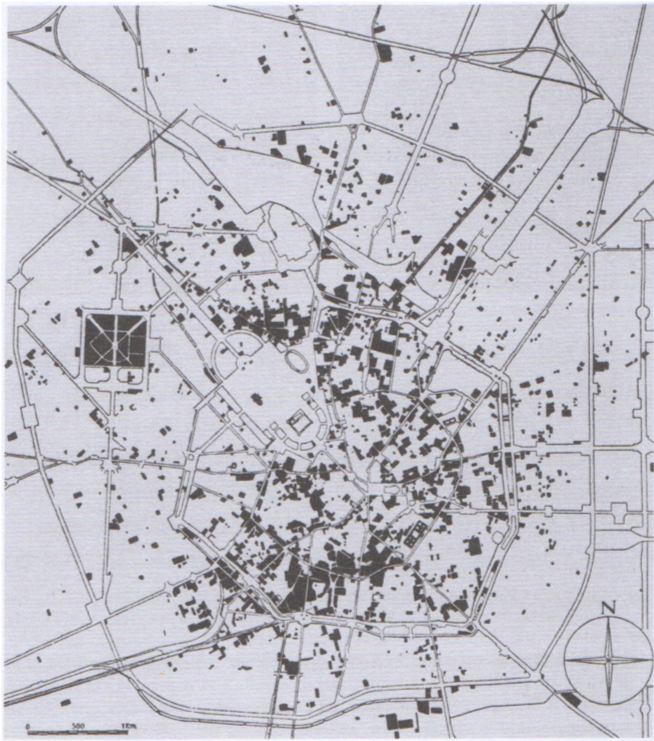

Although three million square metres of Milan remained untouched by the bombs and fire5, at the end of the war, approximately 6-7% of all buildings were destroyed, and 13-15% were damaged6. This implied that about 75,000 dwellings were destroyed (vani distrutti) and 162,000 were damaged, which amounted to 237,000 inhabitable dwellings, and a similar number of families on the streets7. Around 331.800 people lost their houses during the war, and until 1953, the reconstruction development could only restore less than half the demolished rooms with prolonged and enormous housing hardship caused by the bombings (figg. 1 and 2)8.

While in Milan destruction had been scattered and recurrent, in the Polish city of Warsaw urbicide took a more encompassing form. During the Second World War, the capital of Poland became the focus of some of the fiercest Nazi policies aimed at the systematic and scientific annihilation9 of the entire city as a physical, social, industrial, cultural and political centre, including “the biological extermination” of its inhabitants10.

A key aspect of this policy involved the complete obliteration of the entire constructed landscape of Warsaw. It aimed to eliminate completely every aspect and component of the urban structure, leaving no exceptions. The devastation extended beyond buildings, streets and infrastructure; even trees were included in the demolition strategy. The overarching goal was a systematic and comprehensive tabula rasa. This destruction policy was complemented by two other annihilation strategies: segregation and re-founding. High walls with watchtowers were constructed so that the northern part of Warsaw could be enclosed and segregated from the rest of the city. This new zone was turned into an intra-urban prison, which detained 400,000 Jewish citizens and became known as the Jewish Ghetto (figg. 3 and 4)11.

A third element of the Nazi annihilation strategy consisted of the formulation of an entirely new plan for the city. Nazi town planner Friedrich Pabst and his team from Wurzburg considered the tabula rasa as the ultimate basis for the re-foundation of ‘Warsaw, the new German City’ (Warschau – die neue Deutsche Stadt)12. The plans envisaged a city that was only 1/20 of the existing Warsaw. This new German city would be inhabited by 130,000 German inhabitants and 80,000 enslaved Polish people, replacing the previous population of 1,310,000 Varsovians.

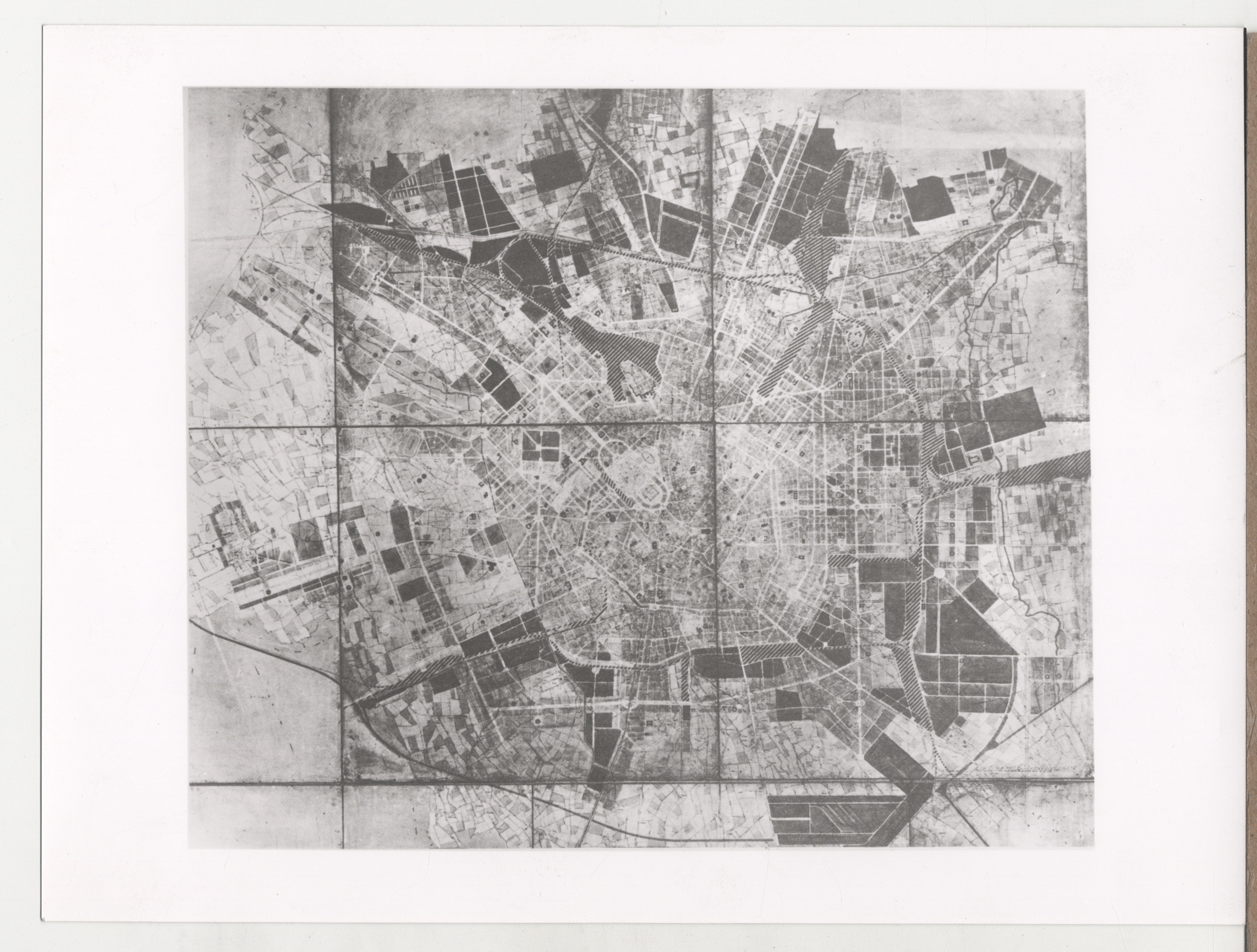

As a result, Warsaw faced one of the most extensive and totalizing destructions during the Second World War. A capital that took seven hundred years to grow was transformed into a material and social “dead city” in a short time13. More than 250,000 Varsovians were murdered during the battle against the Nazi invasion in 193914. In total, 800,000 citizens of Warsaw died during the war15. Next to these personal losses, the built environment was also strongly affected. Between 75% and 85% of the entire city was destroyed16. The Polish monuments were almost all destroyed: 782 historic buildings of the existing 957 were demolished. However, the everyday urban fabric of Warsaw was also strongly affected. In 1939, Warsaw counted 595,000 dwellings. In 1945, only 165,000 were still inhabitable17.

After the Second World War, Warsaw was no more than a field of rubble. Twenty million cubic meters of rubble and ruins were amassed in the downtown area18. Of the total of 3,708 million cubic feet of buildings that Warsaw consisted of before the war, the Nazis demolished no less than 2,600 million. In 1945, Warsaw was confronted with a total amount of rubble of 720 million cubic feet (fig. 5)19.

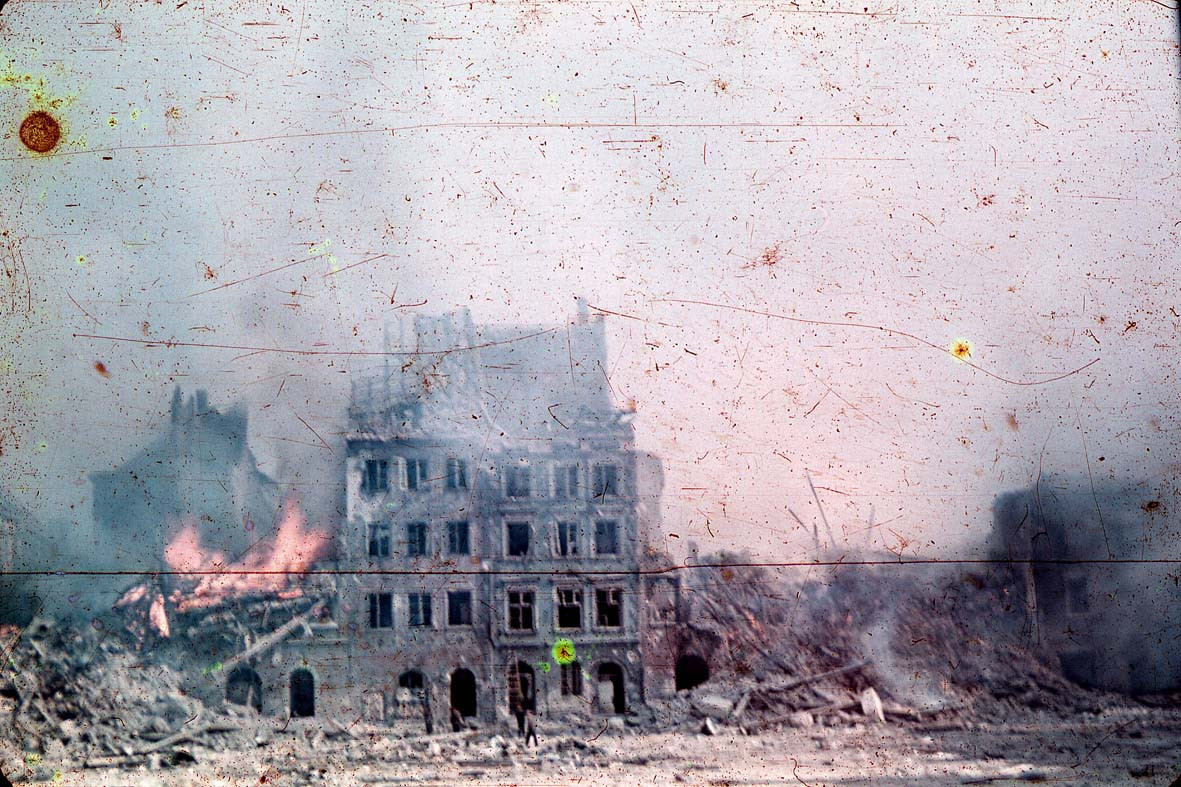

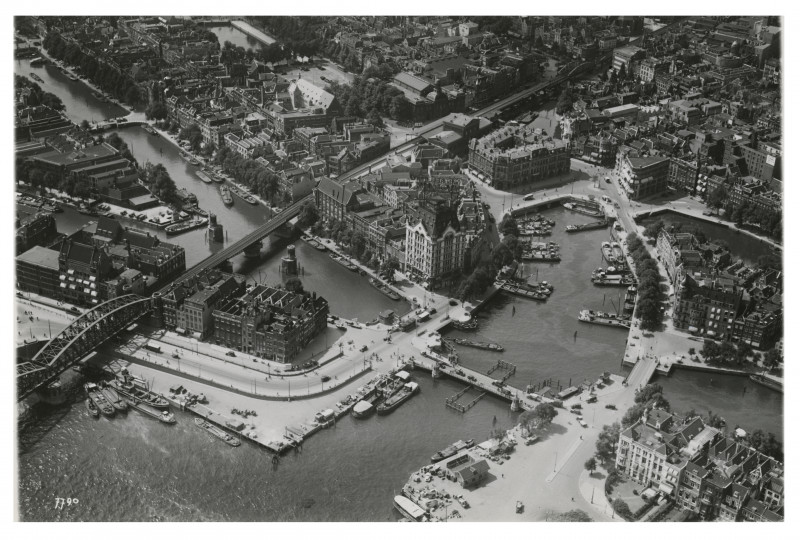

A similar image of vast destruction characterized the Dutch city of Rotterdam as a result of the accumulated bombings by Nazis and the Allies. The former bombed the city centre on 14 May 1940 as a way to provoke the capitulation of the Netherlands. The latter conducted a raid on the western side of Rotterdam in 1943 to halt its function as a logistic hub for the Nazis. After the first Nazi attack, the city centre appeared as a complete tabula rasa with only a few buildings left and the majority of homes, department stores, factories, workshops, warehouses, schools, hospitals, churches and stations entirely destroyed20. The destroyed city covered an area of 258 hectares21. The urban fabric of the historical centre of Rotterdam was turned into a vast open field. The social fabric saw the disappearance of 850 citizens, while 80,000 people or 13% of the population, were left homeless. The estimated cost of the damage was about 420 million Dutch guilders, corresponding to over three billion euros in today’s money22. In the Allied raid in 1943, a further 2,600 homes were destroyed, and approximately 1150 citizens died23. As a result, at the end of the Second World War, Rotterdam was the most damaged city in the Netherlands (figg. 6a and 6b; figg. 7a and 7b).

The different patterns of annihilation soon became the canvas on which a set of modern urban design approaches for reconstruction would be developed. While these reconstruction efforts were very different, retrospectively, they all appear as forms of ‘situated modern urbanism’ that differ from their contemporary counterparts in that they were based on nuanced attitudes to the temporal and agency dimensions of the city.

A first temporal dimension with which many of the reconstruction projects engaged was the traumatic memory of the recent past. Paradoxically, the ‘tabula rasa’ of the Second World War would not lead to celebrating a progressist dimension in urbanism, as so many architects and designers of the modern movement had claimed, but rather to a sophisticated engagement with what existed before. Though this engagement with an annihilated past seems a common denominator of many reconstruction projects, it took many forms.

In the city of Milan, it took the form of an urbanistic census. Eight so-called neighbourhood commissions were given the duty to analyse the character of urban destruction in their respective areas. In order to gain knowledge rapidly about the reconstruction, the city administration had developed the so-called Urbanistic Census (Censimento Urbanistico), which would act as an essential analytical tool for the registration by the various Neighbourhood Committees. The Urbanistic Census consisted mainly of a Statistical Scheme [scheda statistica], comprising an A3 page with a neighbourhood plan (scale 1:2000) and a table in which the damage could be described in numbers or percentages. The data on the plans of various Statistical Schemes were subsequently rewritten and summarized in one Main Plan of Milan (1:5000-1:2000)24. The Urbanistic Census was undertaken in no less than 45 days and offered in this short period a solid reference basis for the conception and development of reconstruction plans25.

While the engagement with the recent past took the form of a quantitative analysis in Milan, in Rotterdam, the symbolic dimension was paramount. At a very early stage, the city government realized that the trauma of the war needed two types of monuments. It commissioned memorials such as the sculpture ‘The Destroyed City’ (1951) by the Russian-born French sculptor Ossip Zadkine (fig. 8), which symbolized the blood and horror of the war with a void in the body like the destroyed heart of the city26. At the same time, however, the city government erected another type of monument that illustrated the solidarity that the annihilation had provoked. A good example was the illuminated sign on the main Coolsingel street with the text ‘Get to work’ [Aan den Slag] (1945), which encouraged the citizens of Rotterdam to join in collaborative action for the reconstruction of the city. As an observer remarked,

Next to representing the memory of the recent past, urban reconstruction projects also seem to be characterized by a positioning vis-à-vis historical urban conditions and planning cultures. In Milan, for instance, radical reconstruction was not a new phenomenon. Before the Second World War, Italian prime minister Benito Mussolini had already implemented the politics of ‘disembowelment’ or sventramento. It was aimed at radically modernizing the existing urban structure with new roads, new urban public spaces and new buildings by using the pickaxe and evacuating the residents from the city centre (“Sfollare le città”)28. Prominent architects, such as Piero Portaluppi and Marco Semenza, won in 1926 the competition for a new urban plan of Milan, which was “based on the idea of the almost total destruction of the actual city, for the reconstruction of a new one29”. Some of these plans were implemented and caused the loss of almost 60,000 dwellings in the city centre30.

This existing culture of demolition and reconstruction created a unique openness to develop new architectural forms, which had already gained momentum in the interwar period in the name of hygienic principles, social betterment, progress and innovation31. Moreover, the previous celebration of the ‘pickaxe’ had also installed an attitude which looked upon destruction as a profitable condition from which the modernization of the city could emerge. As the renowned Italian architect Nathan Ernesto Rogers maintained in 1945, in Milan the urban voids were looked upon as sites of new possibilities:

The numerous demolitions of Milan initiated a unique theoretical debate amongst architects, urban planners and politicians on the relationship between modernity and tradition, about how new buildings relate to the forms and practices of the historical past. This debate would culminate in discussions about context (contesto), ambience (ambiente) and pre-existing ambience (preesistenze ambientali). These concepts allowed architects and urban planners to relate to the past without copying historic buildings and neighbourhoods33. In other words, urban designers and architects could conceive of the past as a ‘context’ or an ‘ambience’ that would be complemented and further developed by their new buildings and neighbourhoods34. The complementarity between tradition and modernity embraced the reconstruction process and debate35, and it will upsurge as a symbolic presence in Milan with the BBPR’s Torre Velasca (1958)36, the emblematic counterforce to abstract modernism at the last CIAM meeting37 and a “homage to a historical centre virtually destroyed by real estate speculators”38, for Manfredo Tafuri. This attitude of openness towards the past was not only a matter of single buildings but also of neighbourhoods and even of the entire city. As architect Giuseppe De Finetti maintained in 1946, “The war is cursed: but there is also a merit (…) it could liberate Milan without further delay from the regulatory plan that is so deleterious for its economy, for its life39”. Hence, the destruction of war was seen by many of De Finetti’s contemporaries as an excellent reason to abandon previous urban plans and to modernize the radio-concentric forma urbis of Milan, which had passed from a metropolis to a megalopolis with a parasitopoli of uncontrolled expansion in the periphery40. From this perspective, the destruction of the war became an opportunity to restructure the entire city41.

In the Polish city of Warsaw, reconstruction was similarly considered as a counterproject for the dwelling conditions in the city before the Second World War. In the interwar period, the city’s development was strongly affected by the speculative logics and rules of private enterprises. Critics had pointed out that this mode of urban development created substantial social disparities. Some of them observed that the large luxury bourgeois flats “had at least ten times as much light and air as the inhabitant of a one-room flat42”. Also the density of inhabitants per flat was criticized and open for improvement43. Reconstruction became an important moment for improving the living conditions, particularly for the working class. The reconstruction plans can be considered a ‘counterproject’ for the existing dwelling conditions that aimed to resolve issues of overcrowding, as well as to guarantee better standards of light and air, and better hygienic conditions. Generally, the reconstruction process was conceived as a transition from a capitalist mode of urban development to socialist values and ways of urban planning.

In Rotterdam, reconstruction was considered an improvement strategy for historical urban conditions from its inception. The urbicide of the Second World War was generally regarded as the perfect opportunity to address many of the problems of industrial pre-war Rotterdam, including overcrowded and impoverished neighbourhoods and the absence of broad-scale modern infrastructures in the existing city. The old medieval centre of Rotterdam was poorly built and highly criticized for its chaotic and haphazard planning. Reconstruction was a major occasion for modernizing the city. This desire for modernization was already palpable among politicians, architects and urban planners even before the war44. The urban destruction was regarded as an occasion to improve the hygienic and spatial qualities of the old urban structure. In the reconstruction plans, an image of a new city was created that was characterized by openness, spaciousness and air, transforming the ratio of open space in the city centre from 44.5 % to 69.4%45.

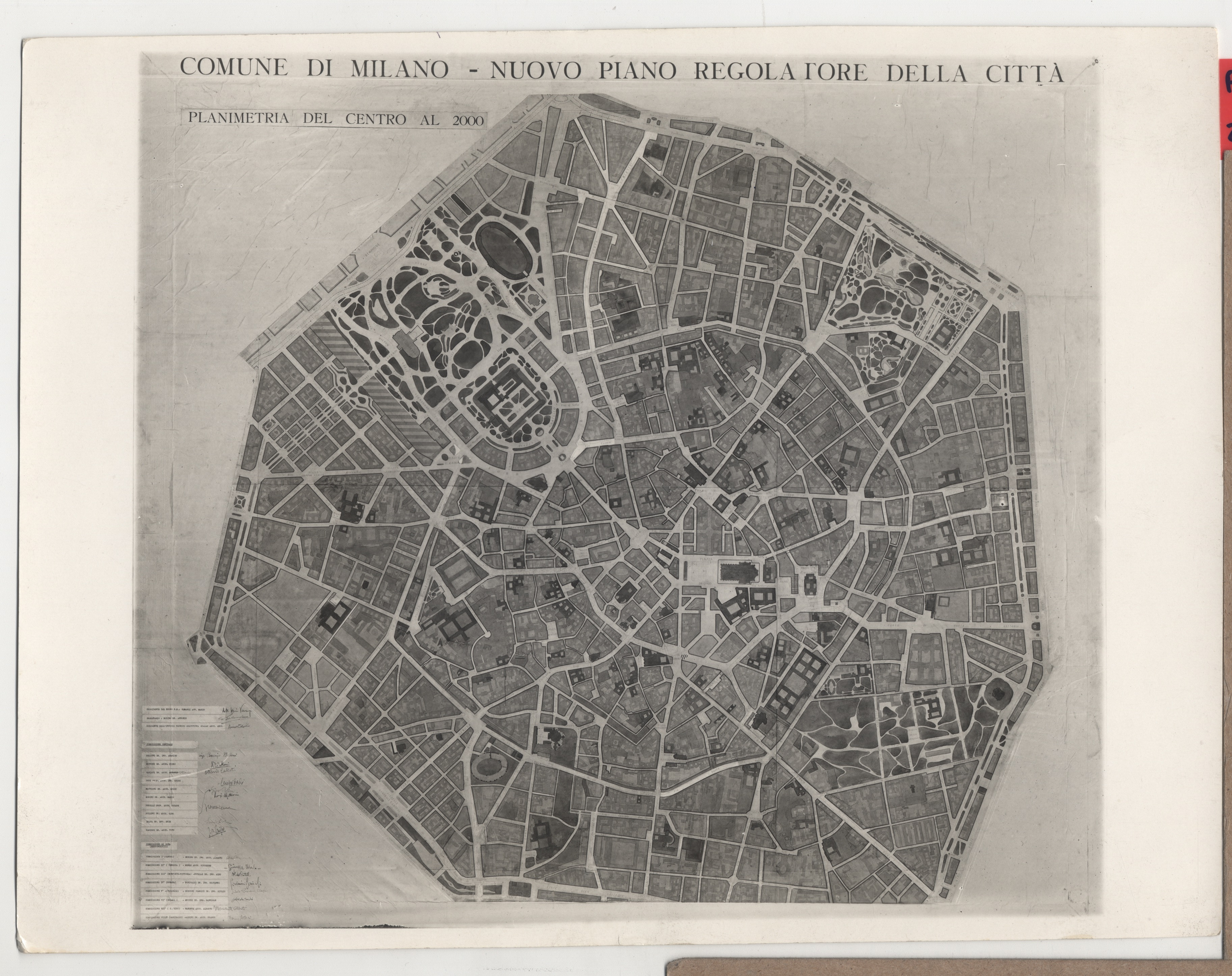

Not only an engagement with the recent memory of the city and its history characterizes the urbanism of the reconstruction projects, but also a vision of the temporal layers of the city. Rethinking the future of the entire city as a ‘matter of reconstruction’ was, from the very beginning, an ambition in Milan. In 1942, a new National Urban Law (No. 1150) was ratified, which paved the way for a new planning instrument: the General Regulatory Plan or Piano Regolatore Generale (PRG). Specific for the PRG was that it considered the entire city. It defined reconstruction as a matter of various temporal layers of urban development, establishing an equivalence between areas that had to be preserved, transformed, rebuilt or expanded. In order to approach the city as this simultaneity of temporal urban layers, the PRG provided the legal basis for expropriation and for the firm embeddedness of plans for single neighbourhoods within the vision for the wider urban territory. Above all, however, the Piano Regolatore Generale was an instrument for considering the various actors and logics that could contribute to the development of the various temporal layers of the city. The plan offered a detailed overview of the investments to be made by the city government to safeguard the collective interest and decide which ventures could subsequently be left to private and individual investors (fig. 9)46.

In Warsaw, the multiplicity of temporal layers was also at the heart of the urbanistic approach to reconstruction. Under the heading “Functional Warsaw”, a notion already proposed in the 1930s by the modernist architects Jan Chmielewski and Szymon Syrkus, the Polish capital defined its urban reconstruction strategy. This encompassed the rapid development of new neighbourhoods that were based on adaptations of pre-war CIAM principles of the so-called ‘functional city’’ such as the Kolo I housing estate (1948-49), which was composed of prefabricated elements, open ground floors and green spaces in between buildings. At the same time, however, Functional Warsaw also envisaged the rebuilding of the entire historic centre, including the reconstruction of eight hundred demolished buildings and the exact reproduction of numerous historical monuments, as a counterforce to the Nazi attempt to eradicate Polish identity and culture47. The reconstruction of Warsaw illustrates a modern urbanistic approach in which different temporal layers coexist: the immediate construction of new housing neighbourhoods combined with the equally important reconstruction of the historical city’s memory and identity.

This coexistence of temporalities required a firm legal basis also in Warsaw. Following the Decree of 26 October 1945, all the land within the borders of Warsaw was transferred to municipal property. The municipalisation of land was considered a basic prerequisite for the capital’s reconstruction, restoration and development. Unlike in Milan, this implied that the state was the sole actor of the reconstruction, engaging with the different temporal regimes of the city. As some observers noted, it deprived private owners of their direct, active contribution to the development of the city48. At the beginning of the 1950s, all of the central districts belonged to the city, while the surrounding belt was mainly privately owned.

In the Dutch city of Rotterdam, the various temporal layers of the future city were also at the heart of the reconstruction plans. Already during the Second World War, plans for rebuilding were drawn up and all the ruins were cleared. After demolishing unrepairable buildings and removal of the rubble, emergency housing and shopping facilities were erected. An essential characteristic of these extremely rapid reconstruction processes was the existence of clear-cut but flexible plans that allowed for immediate action but also encompassed the necessary elasticity to adapt to evolving conditions. City architect Willem Gerrit Witteveen was tasked with a new reconstruction plan just four days after the bombing on 18 May 1940.

Profiting from the ongoing debates on city modernization, city architect Witteveen swiftly formulated his proposal for the initial Reconstruction Plan. A pivotal aspect of his plan was its characterization as a flexible framework. This framework not only aimed to delineate the contours of future urban development but was also conceived as a document intended to stimulate discussions with the various stakeholders engaged in the city’s reconstruction.

However, in July 1942, the occupation authorities mandated a halt to all construction activities. This mandated pause prompted a re-evaluation of the initial plans and instigated a renewed focus on functional modernization. Six years after the inception of the first plan, in 1946, the Basic Plan devised by the new city architect Cornelis van Traa was officially adopted. Like its predecessor, Van Traa’s Basic Plan took the form of a flexible framework rather than a rigid plan. Notably, only 31% of the land was earmarked for rebuilding, allowing significant portions of Rotterdam to remain open for prospective urban transformation and development.

In addition to their distinctive approach to the temporal dimensions, urban reconstruction projects often also displayed a specific attitude towards the question of agency in urbanism. While urban planners or urban designers typically were seen as the unquestioned main agents in post-war urban projects, a conception that would only be fully questioned in the late 1960s, the scope of the agency was often broadened and multiplied in the reconstruction plans of the 1940s and 1950s.

One approach to expanding the concept of agency in urbanism involved incorporating a diverse range of expertise. In the case of Milan’s reconstruction, a notable decision was made not to base the planning and design process only on the ‘internal knowledge’ held by the functionaries of the city administration and city planning offices. Instead, Milan’s mayor and vice-mayors opted to activate the collective expertise available in the city, encompassing private individuals, associations and firms outside of the administration. To achieve this, the mayor established the Study Group for the New Plan of Milan, also called Il Parlamentino by Mayor Grippi, comprising 125 members, the majority of whom were external. These members were organised into 20 Commissions, each responsible for different aspects of the reconstruction process49. This expansive apparatus of commissions enabled Milan to leverage expertise well beyond what was contained within existing city planning offices, ultimately accelerating and enhancing the quality of the reconstruction. This significant reservoir of expertise played important roles in various stages of urban reconstruction.

In contrast, Warsaw’s first president-mayor, architect Marian Spychalski, centralized most of the technical decisions and implementation for the city’s reconstruction50. Several governmental agencies were established to coordinate and direct the various stages of the process. The Bureau for the Reconstruction of the Capital (BOS), installed by the Polish National Council and the inaugural government agency responsible for rebuilding Warsaw, undertook pivotal roles such as damage assessment, debris removal coordination, masterplan drafting and historical building research. Similarly to Milan, BOS sought expertise beyond the existing city administrations, attracting architects, experts and even students who worked on design projects related to Warsaw’s reconstruction51. This collective expertise converged within BOS, which was responsible for crafting the blueprint of the new Warsaw and initiating the reconstruction.

A second way to multiply agency in urbanism, involved initiating public participation in the planning process. While mainstream urban design culture began to emphasise participation only in the late 1960s, public involvement appears to have been a prerequisite in the context of urban reconstruction, particularly in Milan.

The idea of collective participation into the decision-making for Milan’s reconstruction gained broad acceptance and urgency after the war52. This shift towards participation was driven by the new democratic spirit that followed the liberation from fascist dictatorship, marked by events “such as the first democratic administrative consultation after twenty years, the free political elections, the referendum53”. To facilitate this participation, a design competition was considered the most appropriate approach, allowing various ideas for reconstruction to be discussed with the wider citizenry. Hence, an ideas competition was launched by the Municipality of Milan in November 1945, attracting 96 proposals from 106 teams, including renowned architects and urban planners54. These teams were invited to discuss their projects in a public meeting at Castello Sforzesco, fostering a broad civic open discussion to engage the entire city. As a result, the first Piano Regolatore Generale of Milan (1948 - Piano Venanzi), drew upon the competition entry by the AR team (Architetti Riuniti- Albini, Belgiojoso, Bottoni, Cerutti, Gardella, Palanti, Perresutti, Pucci, Putelli and Rogers) whose proposal became a frame of reference for the city’s reconstruction. Moreover, it introduced the proposal of a second centre of the city as a counterforce to the existing monocentric, opening a further discussion for “following studies on the polycentric city as an urban model of development55” (fig. 10).

In Warsaw, the city government recognised the invaluable reservoir of enthusiasm, initiative and perseverance within the returning population. Agencies involved in the reconstruction saw this enthusiasm as a crucial resource to be harnessed. Warsaw employed various means to bring the urban reconstruction project to the citizens and make it a collective effort. The nationally distributed illustrated magazine Stolica (Capital city), an official publication of the Bureau for the Reconstruction of the Capital (BOS), served as a weekly progress report. Articles, reports on cultural activities, and editorial commentary published in Stolica kept the public informed on all matters connected to reconstruction. The resulting engagement of the public in Warsaw’s rapid reconstruction was evident in their contributions of “fifty million man-hours,” particularly in rubble removal56.

In the city of Rotterdam, participation was also considered an essential dimension of urban planning. To sustain public involvement, Rotterdam’s municipality initiated tours. These so-called ‘Reconstruction Rides’ organized by the RET - the city transport service - were very popular with both professionals and the wider public from 1946 onwards57. In addition, the municipality invested intensively in publications that could generate enthusiasm for the reconstruction with different private investors and the broad public. Magazines like Rotterdam Builds! and The City on the Maas, along with films such as And Still…Rotterdam! and Keep At It! showcased the ongoing reconstruction process and conveyed ideas for the city’s development to citizens58. Tours, publications and movies were not only means for involving the public in the reconstruction but also served to acquaint them with the new identity of their city, fostering enthusiasm, pride, hope and optimism among Rotterdammers.

In reconstruction projects, the broadening and widening of urban agency not only involved the inclusion of unconventional expertise and the involvement of the wider public in urban planning decisions but also the recalibration of the relationship between public and private agencies. In the early stages of Milan’s reconstruction, the state assumed a firm regulatory role. As an observer of the early reconstruction efforts in Milan noted, “Since the bombing, private capital in Milan has built more cinemas than new homes59”. In response, the Municipality of Milan determined that certain aspects of the built environment should not be entirely left to private initiative, with housing being a particular focus of public attention. As a result, the municipality started acting as a regulator and took a prominent role in directing the reconstruction process that guided private initiatives.

A distinctive facet of this regulatory role was the municipality’s decision to introduce a period of ‘calm down’ in reconstruction activities. This strategy involved freezing construction resources for a specified period, allowing for the development of qualitative reconstruction plans. Implemented in Milan until 1946, this suspension strategy halted major building activities to prevent the dispersion of construction materials, the overuse of the transport system, and the scattering of workers. The legal approval of the ‘release’ (lo sblocco) occurred in 1947, coinciding with the legalisation and implementation of the first General Master Plan. This strategic approach enabled Milan to formulate a coherent reconstruction strategy, ensuring that private initiatives did not obstruct collective interests and the long-term vision for the city’s development.

In Rotterdam, the implementation and development of the Witteveen plan were orchestrated through two government agencies: ASRO (Advisory Office for Rotterdam City Plan) and DIWERO (Rotterdam Reconstruction Department). These agencies were responsible for formulating reconstruction plans and the actual rebuilding60. These agencies could immediately make concerted action since the destroyed land in the centre was expropriated and requisitioned by the municipality of Rotterdam. Private owners were granted a new building site with an equivalent economic value to the previous one if they committed to rebuilding. Compensation for lost buildings was contingent upon the completion of the reconstruction, calculated based on the selling value during the destruction with added interest61.

However, planning the reconstruction of Rotterdam was not only a matter of state initiative. A group of local businessmen led by Cees van der Leeuw, the director of the Van Nelle factory – a symbol of industrial and architectural modernization - founded “Club Rotterdam.” Collaborating with progressive modern architects of the Opbouw group, they influenced the design of a new functionalist plan for Rotterdam and actively engaged with the Advisory Office for the Rotterdam City Plan. In Rotterdam, the private sector collaborated with the architectural community and became an important agent in the reconstruction process. The Club Rotterdam ensured that the city's economic interests were integral to urban reconstruction.

This concise examination of urban projects in Milan, Warsaw and Rotterdam reveals the rich spectrum of modern urban design approaches developed during the reconstruction processes following the Second World War. The radical absence of the past, due to the vast spatial and social annihilation of the war, seems to have induced a different type of modern urbanism that stands out because of its unconventional engagement with the dimensions of time and agency.

Distinguishing themselves from contemporary urban planning ventures, the urban reconstruction initiatives in Milan, Warsaw and Rotterdam uniquely address the temporal strata of the city. In these urban reconstruction projects, urban design is firmly anchored in the memory of the city, its history and the coexistence of different temporal layers, including future ones.

Simultaneously, these reconstruction endeavours stand out for their unconventional conceptualization of agency in urbanism. Unlike other post-war European urban planning projects that primarily vested agency in state actors, the reconstruction efforts in Milan, Warsaw, and Rotterdam demonstrate an atypical commitment to broaden the scope of urban expertise, to include the wider public in urban decision-making and to recalibrate the relationship between state and private actors.

This dual focus on time and agency outlines the tenets of what we propose to term ’a situated modern urbanism.’ Such urbanism not only illustrates the complex challenge of reconstructing cities after the spatial and social annihilation of war. It also illuminates how, within the precarious and charged context of reconstruction, the tenets of a different urbanistic approach were formulated that offered an alternative to the general incapacity of modern urbanism to engage with multiple time dimensions and diverse agencies.

This research paper is written in response to an invitation from UNESCO and the World Bank.

notes

See: Pertot, Gianfranco. 2016. “Premessa. Milan alla fine della Guerra”. In Milan 1946. Alle origini della ricostruzione, edited by Giangranco Pertot, Roberta Ramella et al., 11. Milan: Silvana Editoriale.

Gribaudi, Gabriella. 2005. Guerra totale. Tra bombe alleate e violenze naziste: Napoli e il fronte meridionale, 1940-1944. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 48. Quoted in Baldoli, Claudia. 2010. “I bombardamenti sull’Italia nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Strategia anglo-americana e propaganda rivolta alla popolazione civile”. In DEP Deportate, esuli, profughe. Rivista telematica di studi sulla memoria femminile 13-14, 39.

See: Pertot, Gianfranco. 2016. Op. Cit., 14.

De Finetti, Giuseppe. 2002. Milano. Costruzione di una città, edited by Giuseppe Cislaghi, Mara De Benedetti, Piergiorgio Marabelli, 436. Milan: Hoepli.

Ivi, 451.

See list of destroyed buildings: Ramella, Roberta. 2016. Op. cit., 307.

Ibid.

Consonni, Giancarlo. 2022. “La risposta al problema della casa a Milano negli anni della Ricostruzione (1945-53).” Territorio 102: 7-13. Consonni Giancarlo, and Graziella Tonon. 1979. “Le condizioni abitative dei ceti popolari e le lotte per la casa dal 1943 al 1948”. In Milano tra guerra e dopoguerra, edited by Gabriella Bonvini and Adolfo Scalpelli, 639-702. Bari: De Donato.

See: Popiołek-Roßkamp, Małgorzata. 2018. “Warsaw: A Reconstruction that Began Before the War.” Conference Proceedings. In Haddad, Elie (Chair), Butelski, Kazimierz, El-Daccache, Maroun. El-Khoury, Roula, and Bogusław Podhalański. Post War Recontruction. The Lessons of Europe (Beirut: Lebanese American University, 2018), 44-52.

Ciborows, Adolf. 1964. Warsaw. A City Destroyed and Rebuilt. Warsaw: Polonia Pub. House, 44.

Ivi, 46.

Ibid.

Ivi, 56. W. Tomkiewicz, Straty kulturalne Warszawy (Warsaw’s Cultural Losses), Warsaw 1948.

Ivi, 7.

Ivi, 62.

These numbers depend upon sources: 75% is mentioned in: Dziewulski, Stanislaw, and Stanislaw Jankowski. 1957. “The Reconstruction of Warsaw.” The Town Planning Review 28, no. 3 (October): 63; 85% is the number stated in Ciborows, Adolf. 1964. Op. cit., 62.

Dziewulski, Stanislaw, and Stanislaw Jankowski. 1957. Op. cit., 64.

Chmielewski, Jan Maciej, and Monika Szczypiorska. 2015. “Could Warsaw be differently rebuilt - alternative history of the city.” Accessed December 15th, 2023. http://www.kaiu.pan.pl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=446:kaiu-1-2015-j-m-chmielewski-m-szczypiorska-abstract&catid=80:1-2015&Itemid=56.

Ciborows, Adolf. 1964. Op. cit., 56-62. See: Wółkowski, Wojciech. 2021. “Architecture in Warsaw, 1939–1944.” Journal of East Central European Studies 70: 689-708.

The Nazi air raid of the 1940 destroyed 25,479 homes, 31 department stores, 2,320 smaller shops, 31 factories, 1,319 workshops, 675 warehouses, 1,437 offices, 13 banks, 69 schools, 13 hospitals, 24 churches, 10 charitable institutions, 25 city and state buildings, 4 stations, 4 newspaper headquarters, 2 museums, 517 cafés and restaurants, 22 party venues, 12 cinemas, 2 theatres and 184 other commercial buildings.

Plan Witteveen, the first reconstruction plan https://www.wederopbouwrotterdam.nl/en/tijdlijn/plan-witteveen/. See McCarthy, John. 1998. “Reconstruction, regeneration and re-imaging, The case of Rotterdam.” Cities 15, no. 5: 337-344.

Fact sheet 75 years of post-war reconstruction in Rotterdam, 2, www.rotterdamviertdestad.nl.

Fact sheet 75 years of post-war reconstruction in Rotterdam, 1, www.rotterdamviertdestad.nl. See Couperus, Stefan. 2015. “Experimental Planning after the Blitz. Non-governmental Planning Initiatives and Post-war Reconstruction in Coventry and Rotterdam, 1940–1955.” Journal of Modern European History 13, no. 4: 516-533.

See: Ramella, Roberta. 2016. Op. cit., 158.

Ivi, 38.

See also Meyer, Hans. 2002. “The promise of a new, modern society in a new, Modern city. 1940 to the present”. In Out of Ground Zero: case studies in urban, edited by Joan Ockman, 86. New York, Munich: Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture, with Prestel.

Statement by Karel Paul van der Mandele, 1945, in “Post-War Reconstruction”. Accessed December 16th, 2023. https://www.wederopbouwrotterdam.nl/en/post-war-reconstruction/.

See Pertot, Gianfranco. 2016. Op. cit., 75.

Ivi, 18.

Ivi, 77.

Ivi, 76.

Ivi, 102. E. N. Rogers, “L’architettura e il cittadino”, 18 July 1945.

These debates took amongst others place in the Milanese architectural magazine Casabella-Continuità (before Costruzioni-Casabella) edited by Ernesto Nathan Rogers in the 1950s.

After the war, this debate was still undeveloped and the quantitative dimension of the destruction revealed the cultural inadequacy in the fields of restoration, urban design to face it. Finally, as De Finetti remarks “the profane thought of rebuild the ancient buildings as they were, … is the only one that has been affirmed with great force in Milan”. De Finetti, Giuseppe. 2002. Op. cit., 436.

About the reconstruction of historical buildings, like the Santa Maria della Pace convent in Milan, by Ignazio Gardella and Giovanni Romano, see Barazzetta, Giulio, Guerritore, Camilla, and Marco Simoncelli. 2023. “An Exemplary Case Study of Post‑WWII Reconstruction in Milan.” Nexus Network Journal 25: 319-338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00004-022-00639-3.

See also Neri, Raffaella. 2019. “Milan 1945, the Reconstruction: Modernity, Tradition, Continuity.” Conference proceedings. In Haddad, Elie (Chair), Butelski, Kazimierz, El-Daccache, Maroun, El-Khoury, Roula, and Bogusław Podhalański, Post War Recontruction. The Lessons of Europe (Beirut: Lebanese American University, 2018), 31.

See Zuccaro Marchi, Leonardo. 2018. The Heart of the City: Legacy and Complexity of a Modern Design Idea. London: Routledge, 100.

Originally in Italian: “Omaggio a una Milano che la speculazione aveva praticamente distrutto”. Tafuri, Manfredo, and Francesco Dal Co. 1976. Architettura Contemporanea. Milano: Electa, 339.

De Finetti, Giuseppe. 2002. Op. cit., 451.

With the war, the last urban plan by Albertini (“Milano del duemila” - 1934) was abandoned. The war highlighted the necessity of concrete plans and sanctioned the rejection of megalomaniac, huge, unrealistic, utopian urbanization of the all Milanese territory (13.100 hectares) designed for) a population of 2-3 millions of inhabitants (1.139.000 inhabitants in 1939 in Milan). Other variations already tried to reduce and reframe the plan before the war, such as the plan by Luigi Lorenzo Secchi.

After the war, the new mayor- Antonio Greppi- and all the vice-mayors have been previously involved in the Resistance against fascism. There was strong political will to contrast the previous regime, which was mirrored in the planning process as well. The abandonment of the previous plans was also expression of a political position. One of the vice-mayors – Vincenzo Rigamonti - was directly dealing with “War damage” issue (“Danni di Guerra”). Pertot, Gianfranco. 2016. Op. cit., 17.

Boleslaw, Bierut. 1951. The six-year plan for the reconstruction of Warsaw. Warsaw: Ksiazka i Wiedza, 91.

Ibid. In 1939 small flats – one/two rooms – were the 68.6% of the total flats. The density of the one-room flat was 3.8 persons per room, the three-room flat was 1.6 and the six-room flat was only 0.9.

See Meyer, Hans. 2002. Op. cit., 89.

Reinhardt, Hans. 1955. The Story of Rotterdam. The city of today and tomorrow. Rotterdam: The Public Relations Office of the City of Rotterdam, 31.

See: Ramella, Roberta. 2016. Op. cit., 37.

See: Mumford, Eric. 2000. The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928–1960. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 182-183.

Chmielewski, Jan Maciej, and Monika Szczypiorska. 2015. “Could Warsaw be differently rebuilt - alternative history of the city.” Accessed December 15th, 2023. http://www.kaiu.pan.pl/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=446:kaiu-1-2015-j-m-chmielewski-m-szczypiorska-abstract&catid=80:1-2015&Itemid=56.

Ibid. One Central Commission [Commissione Centrale], 13 members, coordination role, definition of zoning and functional distribution in the city; Eight Neighborhood Commissions [Commissioni di quartiere], 44 members; Nine Technical Consultative Commissions [Commissioni consultive tecniche], 53 members; One Advisory Board of the Regulatory Plan for completing the permitting applications to build [Commissione consultiva di Piano regolatore], 15 members; One General Inspection board [Commissione generale di controllo], 19 members.

Ciborows, Adolf. 1964. Op. cit., 66.

Ivi, 144.

Until the period of reconstruction, there were three methods for commissioning urban plans that were adopted in Milan: the direct commissioning to well know professional figures, the design by technical bureaucracy, and the ideas competition. The first methods was ill judged because cultural reasons and inopportune political influences. The bureaucratic choice was in stark contrast with the idea of “urban plan as an art work” and with the necessity of fresh innovative ideas. The idea competition remained the main methods for a new plan of reconstruction.

See Ramella, Roberta. 2016. Op. cit., 37.

Riboldazzi, Renzo. 2016. Op. cit., 61.

See: Neri, Raffaella. 2019. Op. cit., 34. See: Bonfante, Francesca, and Cristina Pallini. 2015. Op. cit., 142-160.

Ciborows, Adolf. 1964. Op. cit., 147.

“Fact sheet 75 years of post-war reconstruction in Rotterdam”, 1, www.rotterdamviertdestad.nl.

“Post-War Reconstruction”. Accessed December 16th, 2023. https://www.wederopbouwrotterdam.nl/en/post-war-reconstruction/.

De Finetti, Giuseppe. 2016. Op. cit., 441.

Engineer Johan Ringers was the government minister who oversaw the entire reconstruction. “Plan Witteveen, the first reconstruction plan”. Accessed December 12th, 2023. https://www.wederopbouwrotterdam.nl/en/tijdlijn/plan-witteveen/.

Reinhardt, Hans. 1955. Op. cit., 8.

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Lorenzo Mingardi (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Lisa Henicz

Luigiemanuele Amabile Alberto Calderoni

Lorenzo Grieco