In 1156, King William I of Sicily mounted a campaign of destruction against the city of Bari, in Apulia, intending to punish its inhabitants for their insubordination. Despite the citizens’ pleas, “the most powerful city of Apulia, celebrated by fame and immensely rich, proud in its noble citizens and remarkable in the architecture of its buildings” was swiftly transformed into piles of rubble, as a contemporary chronicler recounts. Focusing on the twelfth-century destruction of Bari, this paper engages with the theme of urban destruction in the past. The study of destruction in its various forms, be it because of natural catastrophes, conflicts, economic rapaciousness, or urban renovation, is a topic which has been garnering an increasing amount of cross-disciplinary interest in recent years. Within this context, a vibrant current of work examines the concept of urbicide, or the wilful destruction of a city’s buildings deliberately undertaken to destroy urbanity. While this concept has been employed productively to study modern-day examples, it has been applied much more cautiously to the study of cities in the pre-modern world, leaving a significant gap in the scholarship. Yet, the framework of urbicide can be a valuable tool for understanding destruction in the past. When applied to the Middle Ages, for instance, it can help highlight what constituted “a city” and “urbanity” in the perspectives of a medieval urban resident and allow us to explore the motivations of the destroyer as well as the reactions of observers and contemporaries. Utilizing a combination of chronicle, documentary and material evidence, this paper will explore the destruction of Bari, focusing on the its violent transformations and on the significance of the buildings that were targeted. It will argue that the destruction aimed not so much at obliterating the city in its entire physical entity, but rather specifically at erasing its urbanity, effectively committing an act of temporary urbicide.

Having won this victory, the king [William I of Sicily] led his army up to Bari; the population of the city came out to meet him without weapons, and begged him to spare them. But looking at the ruins of the royal citadel which the people of Bari had destroyed, he said, ‘My judgement against you will be just: since you refused to spare my house, I will certainly not spare your houses […] the walls were first brought down to ground level, and the destruction of the entire city followed. That is why the most powerful city of Apulia, celebrated by fame and immensely rich, proud in its noble citizens and remarkable in the architecture of its buildings, now lies transformed into piles of rubble.

Hugo Falcandus1

This dramatic narrative recounts the events that marked the final stages of a large-scale rebellion led by the city of Bari, among others in Apulia, against the Norman power centred on the Sicilian court of Palermo. At the time of these events, Bari had been under Norman control for about 85 years, since Robert Guiscard’s conquest of the city in 1071, but had displayed little tolerance for Norman authority during this period. The city not only possessed a rich history as a Byzantine provincial capital, but also boasted a strong tradition of local politics which had, on occasion, led to periods of independent rule. About a year before the events narrated above, its citizens had allowed a Byzantine army to enter the city and use it once again as their Apulian foothold, from which to mount a broader and more generalised offensive against Norman control over the region2. This passage is the most renowned and frequently cited account of the city’s destruction, ordered by the Sicilian ruler William I, after regaining control of the city. Its author, (pseudo) Hugo Falcandus3, was a contemporary writer based at the Palermitan court and he is generally recognised as possessing considerable insight into the political events of his time, notwithstanding his significant biases. Falcandus depicts a clear “eye for an eye” dynamic of destruction: the splendid architecture of the former Apulian powerhouse being razed in retaliation for the destruction of William’s own stronghold within the city, the Norman fortress, which had been damaged during the insurrection.

The deliberate, targeted destruction of the built environment featured frequently in the medieval world as a tool of political violence, as it still does today. Medieval chronicles are rife with reference to urban towers, rural castles, city walls, and other significant monuments being destroyed during struggles for power. These acts were not always, and often not primarily, driven by strategic military necessities but instead stemmed from a more complex dynamic involving both symbolic and practical rationales. While deliberate political destruction is still being investigated in a rather piecemeal fashion by medieval historians and archaeologists, it is of great significance to the study of medieval politics and urban life. Studying the logic behind destruction allows us to understand better not only the tangible manifestations of power and violence in relation to the materiality of the built environment, but also the less tangible world of ideas: about space, authority, and identity more broadly. Combining these elements then allows us to look at those complex phenomena that inextricably link the physical and social fabrics of the city with the collective memories and identities of its inhabitants.

This paper will explore the destruction of Bari, focusing on the types of buildings that were targeted during the attack. Medieval sources testifying to destruction are notoriously hard to interpret: narrative accounts often employ rhetorical language when describing episodes of destruction, intentionally drawing parallels with famous ancient examples (e.g. Troy and Carthage) or biblical ones (e.g. Shechem, Babylon, or Jericho). At the same time, the archaeological evidence presents its own set of issues. Even when traces of destruction are identifiable during excavations or surveys, there are substantial methodological risks in attempting to link them precisely to historical events and ascribing them to deliberate actions, particularly within urban settings4. Despite these challenges, the destruction of Bari is well documented by a wealth of textual sources produced both from within and outside the city. These have been meticulously examined by historians, with the objective of comprehending the repercussions of King William’s fury on the city’s structures. In addition, archaeological findings contribute to our reconstruction of the medieval city. Utilizing a combination of these sources, the initial section of this article will provide an overview of Bari’s urban landscape at the time of the attack. Then, it will focus on its violent transformations and on the significance of the buildings that were targeted, arguing that the destruction aimed not so much at obliterating the city in its entire physical entity, but rather specifically at erasing its urbanity, effectively committing an act of temporary urbicide.

The concept of urbicide has gained increasing prominence since the 1960s, particularly, though not exclusively, within the work of architects, sociologists, journalists, geographers, and contemporary historians. It has been used to study a variety of phenomena relating to the destruction of a city not just in its physical manifestations, but also as a living organism and as a political community5. The primary objective of an act of urbicide is understood to be that of “destroying urbanity” by eradicating the structures that define a city as such and which embody civic life and ideals6. It thus provides a valuable framework for examining a particular form of urban destruction in which demolition is carried out as a type of political violence aimed at affecting the inhabitants in practical, ideological, and cultural terms, through the targeted destruction of the buildings. The urbicide framework found particular resonance in relation to the urban destructions undertaken during the Yugoslavian conflicts of the 1990s, but in recent studies it encompasses a broader spectrum of cases and causes (from warfare to speculative developments, industrialisation/deindustrialisation, ideology, and more)7. Nevertheless, its reception within studies of deliberate destruction in the ancient and medieval past has been more cautious. Part of the reason is linked to the kind of resources, in terms of time, expenditure, and technological abilities required for effective urbicide. In a recent volume on city destruction in Ancient Greece, for instance, the editors rightly remarked on the rarity of urbicide in the ancient Greek world. They noted that “the notion of victors systematically razing constructions to the ground is a vivid and efficient literary symbol, but it is far removed from the realities and efforts it implies”8. This is clearly also linked to the matter of the reliability of the written sources, which are not necessarily accurate in quantifying the extent of the damage, or at least impossible to verify. Finally, contemporary scholars have also at times expressed hesitancy regarding the possibility of using the concept of urbicide to explain destruction in the past. That it is because it relies on a specific cultural construction of the city that encompasses an idea of ‘urbanity’ which might not always be fitting the context of historical cities9.

This paper will assess the applicability of the urbicide framework to medieval city destruction. It does not aim to serve as a definitive test for the universal validity of any specific model of urbicide applied to cities in the past. Instead, it employs urbicide as a lens to highlight distinct characteristics of medieval urban destruction. This framework allows us to reflect more deeply on the concept of urbanity as understood by medieval urban dwellers, as well as highlighting the significance and the underlying principles of a destructive practice which appears pervasive in the medieval world.

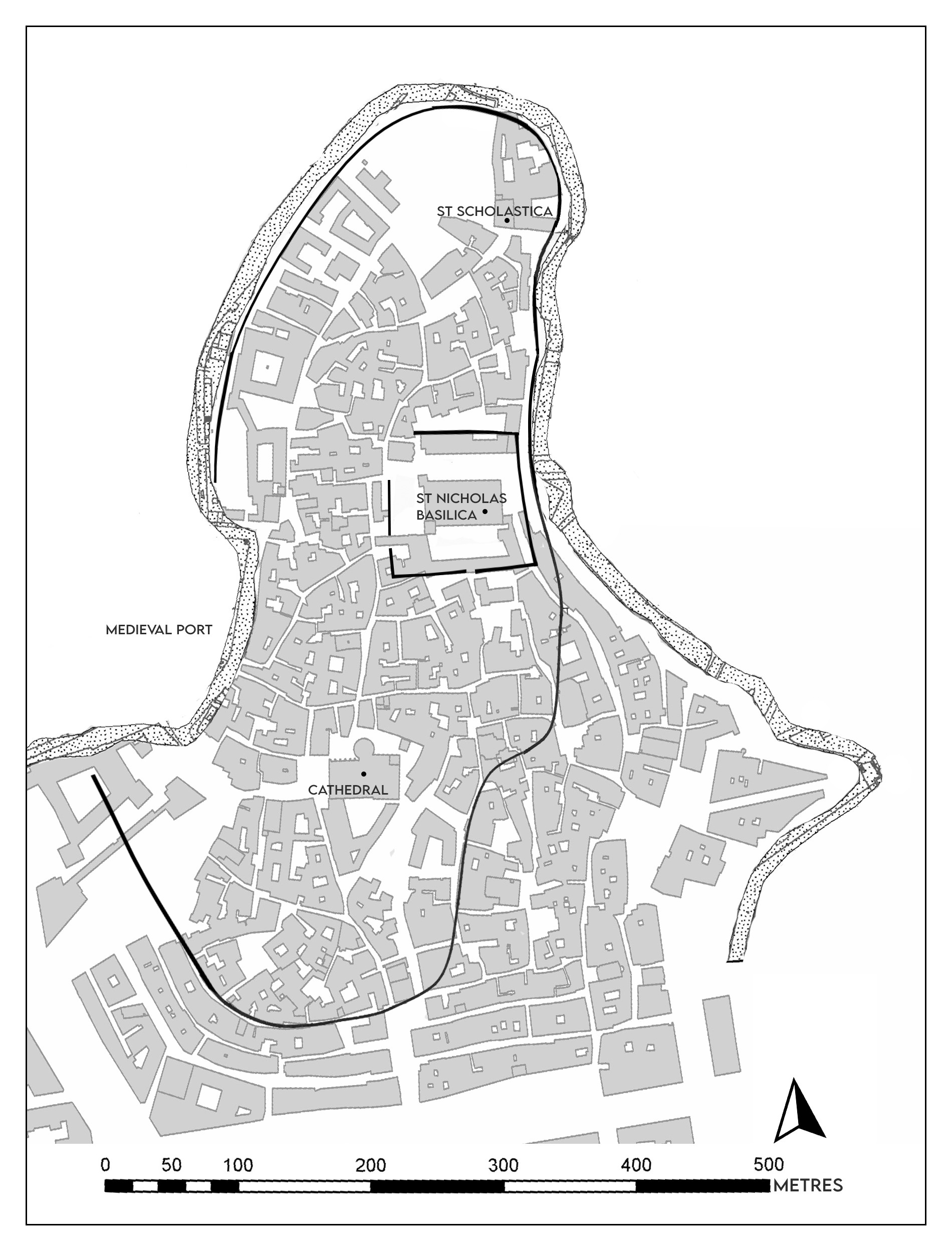

Medieval Bari occupied the small peninsula known today as “Bari Vecchia”, encircled by the sea to the north, west, and east, and protected by defensive walls (Fig. 1). During the early medieval period, the city underwent periods of Lombard, Islamic, and Byzantine rule, all while maintaining a robust tradition of local political activity. By the time of its destruction, it had enjoyed centuries of political and economic significance, in virtue of its historical role as the capital of the Byzantine thema of Longobardia, of its economic and trading networks, and its advantageous position on the Adriatic Sea coast. This political tradition and the city’s enduring wealth, in addition to the presence of an active and well-established Jewish quarter, all contributed to a twelfth-century urban space marked by centuries of diverse influences.

Before the conquest by the Normans, the political heart of the city had been the praetorium, also known as the catepan’s court, a complex comprising several structures and most likely fortified10. After Guiscard’s conquest, however, this area underwent a significant transformation into a religious centre, with the construction of the St. Nicholas Basilica, aimed at housing the relics of the saint which had been brought from Myra in 1087 (Fig. 2). The construction of the Basilica resulted in a city that revolved around two major religious centres (in addition to an array of smaller churches), the Cathedral of St. Sabinus and the new Basilica. This conversion of the old Byzantine praetorium area into a religious centre carried a significant political message from the new authority and St. Nicholas became a prominent pilgrimage destination, enjoying substantial patronage not only from the Normans but also from the papacy in Rome, especially in the person of Urban II11. The Norman castle, which was located near the port, one of the most vital assets of the city, served as another focal point of political authority and the sources show that civil judges operated here at least from 110012.

The residential network of the city was dense and compact in its layout13. By the twelfth century, the typical middling house in Bari was a casa/domus orreata, a two-storey building often organized around a shared court that could house wells and guttae for water collection and waste disposal. A staircase, often external and sometimes made of stone (scala petrinea), offered access to the upper floor. A notable architectural feature frequently mentioned in the written sources was the guayfo, a large terraced platform or balcony that overlooked either the courtyard or the public road. References to upper floors, staircases and guayfi, along with frequent mentions of arches, indicate a city where building by exploiting the space vertically was the norm. This architectural model, inherited from the Byzantine period, appears to have persisted even during the Norman era, alongside an increasing proliferation of towers and of tower-houses, a kind of structure which started appearing in the 11th century and would then become characteristic of the 12th. Several later examples of Bari tower-houses can still be observed in locations like Vico della Torretta, via Martinez, via Palazzo di Città, and Piazza Cola Gualano, although these structures have undergone modifications over the centuries (Fig. 3)14. The changing forms of the buildings are accompanied also by changes in the arrangement of the residential patterns: during the twelfth century, written sources document a growing agglomeration of buildings in insulae and in vicinii, dense neighbourhoods organized around a pole of attraction which could be an élite residence or a (sometimes private) church. The concentration of the urban environment is further testified by the presence of houses and tower-houses built right against the defensive walls of the city, once again indicating a dense, compact style of living15.

When the destruction began, the first structure to be destroyed seems to have been the city walls, as reported by Falcandus. It is worth noting that this was not the first instance of the Normans destroying Bari’s defensive walls. In 1139, a previous attack led by Roger II using siege machinery had caused substantial damage to the walls, so much that it had also resulted in the collapse of the adjacent residential buildings16. We have other evidence, beside Falcandus’ report, that the walls were heavily compromised in the 1156 attack, including the collateral (perhaps partial) destruction of a monastery which was situated by the fortifications, S. Bartolomew iuxta antitum muri. An inscription commemorating the monastery’s restoration in 1180 explicitly stated that this reconstruction was deemed necessary due to its “diruta sorte gravi”17. The precise extent of the wall’s destruction is difficult to estimate, due to the lack of definitive archaeological evidence, though a combined study of extant architectural and written evidence has shed light on a section of their likely location (fig. 4)18.

The destruction of the city walls was significant beyond its military implications. The murum urbis constituted a key element in the citizens’ conceptualisation of their own city. While certain neighbourhoods, houses, and churches could extend beyond the physical confines of the city walls, the walls were the visible marker that defined a city as such and helped define its inhabitants as citizens. Consequently, they often became prime targets during medieval urban destructions19. In the mid-7th century, for example, Lombard king Rothari attacked a series of Ligurian cities and, after their defeat, he stripped them of their defensive walls. The chronicler Fredegarius, documenting these events, noted that the king “destroyed the walls to the foundations, so that those cities would be called villages”20. The destruction of the walls effectively transformed the cities into something lesser, effectively negating their ‘cityness’. In the case of Bari, the Annales Ceccanenses records that in the year 1156 King William of Sicily fought against the Greeks near Brindisi, and he defeated them. Then he went to Bari and destroyed it, and “fecit ex eo villas”21. Some have interpreted this passage to mean simply that the population was dispersed into the countryside, which indeed was the case, as we will see below. However, when comparing this passage with the earlier one by Fredegarius, it becomes evident that the destruction of Bari’s walls was also understood to mean a symbolic vilification in the same vein as that which befell the Ligurian cities, transforming it from a great city to a more rural place through the destruction of its boundaries.

The demolition of the city walls was also part of a deliberate effort by the king to forcibly alter the status of its inhabitants, effectively stripping them of their citizenship by erasing both the conceptual and practical boundaries of their city. A few documents dated to the years immediately following the destruction, recording the transactions of former citizens who had relocated to neighbouring Apulian areas, bear witness to the profound impact of this attack on both their identity and legal standing. For example, in 1157, when a certain Kiramaria decided to sell her properties to someone named Iohannes, both parties are described as “olim barenses”, meaning “formerly Bari citizens”. In 1158, it is Bisantius Struzzus, son of Bisantius who describes himself as “olim civitatis Bari”. Similar formulations can be found in various documents from the same period22. In normal circumstances the agents involved in these transactions would be referred to as simply ‘Bariots’ or ‘citizens of Bari’, typical of the formulaic language employed by the notaries registering the acts. The modification of these formulae is thus made even more significant by the fact that it disrupts an established notarial custom and can thus be perceived to have specific legal significance. It can be seen as an attempt at committing to written memory the former juridical status of the individuals, essentially resisting its loss and the associated loss of the legal rights and privileges that came with it.

The erasure of the status of ‘city’ for Bari through the destruction of its walls also meant an erasure (or, at least a temporary suspension) of the status of citizens for its former inhabitants, visible in their notarial activities. At times, we also get a glimpse of the emotional dimension of the destruction, most likely a reflection of individual feelings: two fragments of charters include the sentences: “Ut barenses Barum revertantur” and “si ex indulgentia predicti domini nostri regis iamdicta civitas recuperata fuerit”, expressing the wish to be able to return to the city23.

It was not solely through the destruction of the city walls that this transformation was enforced, but also through that of the residential environment of the city.

As the chroniclers report, the king granted the citizens two days to vacate the city with their belongings before embarking on the demolition of buildings: “The king arrived with his army, a strong hand, and an outstretched arm and he forcefully besieged the city and he captured it, though he allowed them [the citizens] to depart freely, moved by compassion24”. “They were allowed a truce for two days, during which period they were to leave, taking all their things with them25.” The choice to let some time lapse, between the capitulation of the city and its destruction, underscores the fact that this was executed as a deliberate act of systematic political violence, rather than being driven by military necessity.

Evaluating the extent of the destruction within the city’s residential network is an endeavour fraught with significant challenges. From the point of view of the material evidence, one of the foremost difficulties lies in the practicality of conducting extensive archaeological investigations, particularly in an urban centre like present-day Bari, where the constraints of space, infrastructure, and development make large-scale excavations virtually unfeasible. The other is the methodological challenge posed by the attempt to connect with certainty any evidence of destroyed residential buildings with specific historical events that might have caused their ruin. Indeed, no indisputable trace of the 1156 destruction has ever been found in the archaeological record of the city. The clear evidence of medieval residential buildings uncovered through excavations in the old city centre, for instance, is now believed not to be directly linked to the 1156 events, but rather to urban restructuring26. The documentary evidence is also of difficult interpretation. If we look at some surviving documents dated to the first decade after the destruction, we find records of property transactions involving houses that appear to have survived relatively unscathed27, providing a contrasting perspective to the image of the city as a “pile of rubble,” as described by Falcandus. At the same time, other documents produced in the same years do include references to properties within the city that were either destroyed or damaged. For example, Kiramaria, whom we encountered earlier, mentioned in one of her property sales a “casili diruto quo est intus diruta civitate Bari28.”A foreign eyewitness, the Jewish author Benjamin of Tudela, passed through Bari less than five years after the destruction, during his Mediterranean journey and described it as a “great city destroyed by King William of Sicily”. He added that by then, it was “not only devoid of Israelites but also of its own people, and entirely ravaged29.” Some years later, we find people selling destroyed houses within the city30, and even at the turn of the century there are still mentions of destroyed properties in the sources: in 1199 a casa diruta was confiscated and in 1200 the noblewoman Laupa sold “unam domum in maiori parte diruta”, located in an aristocratic neighbourhood31. These accounts suggest that at the close of the twelfth century, there were still visible scars on Bari’s urban landscape resulting from William I’s demolitions, in the form of partially destroyed private buildings. Rather than treating this varied evidence as contradicting, turning to the concept of urbicide can be a useful way to approach the issue of understanding the impact of the residential destruction, provided we approach it in a qualitative, rather than quantitative, manner. As mentioned above, one of the difficulties in applying the concept of urbicide to the pre-modern world is that complete and utter destruction was hard to achieve in practical terms, contrarily to what can be achieved with modern-day tools. This is especially true for twelfth-century Bari, since, by the time of the 1156 event, many of the buildings in the city centre would have been constructed from stone rather than perishable materials. Systematic destruction of these structures would have been a lengthy and costly undertaking. However, I posit that achieving large-scale destruction was not necessary to accomplish the goal of erasing urbanity. Especially when combined with forced exile, the targeted destruction of a few significant buildings would have been sufficient to dismantle the local political and social networks that were deeply ingrained in the city’s residential fabric. William’s primary aims were precisely the disruption of these networks and the alteration of the city’s identity, rather than the total obliteration of every physical urban structure.

In medieval cities like Bari, where neighbourhoods could coalesce around specific elite residences, these buildings served both as visible markers of the social status of their owners and as practical centres of power. Abundant evidence reveals that in Bari, these houses were pivotal locations for arranging meetings, making decisions, forming alliances, and striking deals32. They were the physical centre of a social network that extended beyond direct family members to encompass relatives and a broader array of associates33. As such, we often find competing groups vying for their control. During periods of internal factional struggle, for instance, the demolition of the house of a political enemy could mark the victory of the destroying party and there are numerous references to deliberate house destructions in Bari which are closely tied to periods of internal strife. Towers and tower-houses, in particular, formed a visible landscape of power meant to dominate the skyline of the city and, as such, their control had significant consequences in political terms. During Robert Guiscard’s campaign to conquer Bari, one of his notable demands was the surrender of the house of Argyros, a local leader, “since he knew that it was higher than the neighbouring houses” and he “hoped that by obtaining it and from its elevation he might control the whole city34.” They were both a practical means of domination and a symbol of acquired authority. Consequently, erasing these conspicuous landmarks from the urban landscape would have signified the removal of the family’s authority from the city in similarly symbolic and practical terms.

From a material perspective, as previously noted, Bari’s urban fabric consisted of a tightly interconnected system of buildings that were often interdependent. Houses not only shared internal courtyards but also main walls, supporting arches, and passageways35 (Fig. 5). In this context, the targeted destruction of even a few selected buildings had the potential to disrupt a much wider area than the single residence. Even assuming that only a percentage of the city’s buildings suffered severe damage, the written sources testify to the impact on the inhabitants. In documents issued in the years after 1156, not only the city is frequently described as diruta, but various contracts and agreements often include expressions of hope that “through the leniency of our king, we might one day recover our city36.” These sentiments underscore the enduring impact of the destruction on the city’s identity, the longing for its restoration, and the feelings of denied belonging to its collective on the part of the exiled citizens, regardless of the precise quantitative extent of the residential demolitions.

The rationale behind the choices made during the destruction becomes even more apparent when we consider another type of building that characterized the urban landscape of Bari. While the walls and residential buildings were the primary targets of William’s army during the attack, there is a notable category of structures that were largely spared: ecclesiastical institutions. Except for the case of St. Bartholomew mentioned earlier, there is no clear evidence to suggest that churches and monasteries were systematically targeted in the assault.

An examination of religious buildings mentioned in documents from the 12th and 13th centuries revealed that out of 32 known churches from the earlier period, at least eighteen still existed in the later era37. The absence of mentions of the others in written sources does not necessarily indicate their ruin either, as they may have continued to exist. One papal document from 1177 does mention the dilapidated condition of the church of St. Nicholas de lu portu, describing it as “diruta38.” However, archaeological investigations conducted in several Bari churches, including St. Nicholas de lu portu, did not reveal any evidence of violence datable to the mid-twelfth century39. The fate of the cathedral of St. Sabinus has also been debated. An older tradition believed that the restoration the cathedral underwent in late twelfth-century may have been repairs due to following the Norman attack, though there is no direct evidence to support this interpretation40. Additionally, a document from 1160 records a series of intact houses adjacent to the cathedral, suggesting that this area may not have been significantly affected by the destruction41. It is more plausible that the refurbishment efforts were driven by competition with the Basilica of St. Nicholas, which enjoyed substantial wealth and patronage due to the relics of the revered St. Nicholas of Myra. The Basilica was indeed spared any damage during the attack, a fact that contemporary authors explicitly documented. As previously mentioned, this church was not only a significant pilgrimage centre but also a stronghold of Norman power in the city, which would have guaranteed its protection (Fig. 6). Similarly, other religious institutions closely associated with royal authority seem to have survived, such as the monastery of St. Scholastica. Four years after the destruction, the monastery was under the governance of domina Eustochia, who was the “sister of Lord Maio, the great admiral of admirals, and of Lord Stephen, likewise a royal admiral”, two of the most high-ranking figures at the Palermitan court42. It is likely that Eustochia rose to the role of abbess even earlier, as Falcandus informs us that Maio “appointed his family and relations to the highest offices of the realm” and “gave clerics appointments of great honor” as early as the summer of 115643. This would suggest that St Scholastica had also managed to remain unscathed, confirming the image of relative continuity in the religious life of the city.

In addition, this also reveals that the destruction was not indiscriminate, but rather followed a precise rationale and was the result of deliberate consideration on the part of the destroyers. We know that the St Nicholas area, which had been rebuilt after substantially reworking the site of the former Byzantine praetorium, was not just a church, but a whole complex that still was fortified in the 1150s44. This allowed it to function as a relatively independent neighbourhood, a sort of city within the city, which also housed markets and even a xenodochium for travellers45. In the Breve Chronicon de Rebus Siculis, it is explicitly mentioned that “the neighbourhood of Saint Nicholas was spared out of devotion so that the pilgrims who came to worship that saint could find the necessary supplies46.” The decision to spare this area thus served two distinct purposes: the first was to support a prestigious religious centre that had been closely linked to the southern Italian Norman power since its establishment. The second was to maintain an area within the city that still retained a degree of liveability, including access to food and essential supplies for travellers, as indicated by the Chronicon. The key detail is that this was not intended for the citizens themselves, but rather for pilgrims coming to venerate St. Nicholas’s relics and other external visitors. The choice to spare St. Nicholas, along with other religious institutions in the city, thus further illustrates a rationale of destruction aimed at targeting the urbanity of the place, the physical landscape that fostered the daily lives of its citizens, rather than engaging in indiscriminate demolition of the entire urban area. William’s strategy effectively involved the targeting of the destruction so that the city would become unliveable and inaccessible to its own citizens, while carving out spaces which could continue to operate as enclaves with their own characteristic urban character, different and capable of surviving independently from that of the main city.

There are different ways of evaluating the success of William’s endeavour. On one hand it seems clear that unlike other medieval cities that suffered destruction47, Bari was never fully abandoned. Even outside of the confines of the St Nicholas neighbourhood, we know that there was a degree of activity in the city already in the years immediately following 1156, as testified by the documents which record the presence and the work of the royal curia in Bari48. However, for the majority of the population, the situation must have been quite different. As the Chronicon recounts, “the inhabitants of Bari […] did not return to their properties if not after the death of king William I, [when] queen Margaret his wife had them recalled; and for 11 years they dwelled as exiles, living under their vines and their fig trees. […] Instead, the leading men among the citizens of Bari travelled with their families to the […] emperor of the Constantinopolitans, who gave them the city of Spita/Spica to settle in49.“ The long exile appears confirmed once again by the documentary sources, as still in 1167 they record the transactions of former inhabitants who continued to reside in neighbouring areas and on occasion even include their hopes that one day the city would be returned to its citizens, as seen above50. The memory and longing for Bari’s restoration clearly persisted among its displaced residents.

The impact of the destruction on the people was profound and enduring even after the royal pardon allowed for their return. Approximately half a century after the events, local judges compiled the Consuetudini Baresi, a heterogeneous written collection of customary laws that likely combined older oral customs with written laws51. Throughout this compilation, the demolition of the city is a recurring theme, with numerous references to the loss of acts and chartae in connection with the city’s destruction. Consequently, many entries in the Consuetudini are dedicated to providing instructions on how to resolve disputes related to dowries, property ownership, lost documents, debts, and various other disagreements when the original proofs were lost in the “destructionem patriae52.” The compilation of the Consuetudini, perhaps even more than the accounts of chroniclers, serves as a vivid testament to the anxieties and disruptions caused by the widespread losses that followed 1156 and by the breaking down of the networks that regulated everyday life as a consequence of it.

This evidence makes it clear that William was extremely successful in committing a form of temporary urbicide against the Apulian centre. Bari experienced a deliberate act of political violence that was not intended to obliterate the entire urban fabric but rather to dismantle and harm specific structures or groups of buildings closely associated with the identity, politics, and daily life of its citizens. The city walls and the residential buildings were the main targets, while the major religious institutions of the city, especially those which had a connection with the Norman authority, were allowed to remain mostly intact. Notably, St. Nicholas Basilica was left standing and was allowed to function as an isolated urban island, distinct from its surrounding environment. Using the framework of urbicide allows us to study the events of 1156 beyond answering the simple question of whether the city was truly empty or thoroughly destroyed. Firstly, it enables us to engage with the information provided by textual sources in a different manner: instead of solely searching for the “truth” concerning the physical extent of the destruction, it allows for an examination of the choices made regarding which structures were to be demolished or spared. This analysis can be carried out with a focus on the impact on the lives of the citizens, their sense of identity, and their daily routines within the city. In this context, it becomes necessary to detach the concept of urbicide from specific considerations of scale or of the practical feasibility of destruction. Secondly, the framework of urbicide need not be reserved for the study of contemporary destructive events. Rather, it can also offer a valuable tool for contemplating what constituted “a city” and “urbanity” in the perspective of a medieval urban resident, allowing us to explore the motivations of the destroyer as well as the reactions of observers and contemporaries.

notes

Falcandus, Hugo. 1998. The History of the Tyrants of Sicily. Edited and translated by Graham A. Loud and Thomas Wiedemann. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 73-74.

For an overview of the political situation: Lavermicocca, Nino. 2017. Bari Bizantina: Origine, Declino, Eredità Di Una Capitale Mediterranea. Bari: Edizioni di Pagina.

For the question of Falcandus’ identity and his reliability: Loud, Graham A. 2015. “Le Problème du Pseudo-Hugo: qui a Écrit l’Histoire de Hugues Falcand?” Tabularia ‘Etudes’ 15: 39-55.

Santangeli Valenzani, Riccardo. 2013. ‘Dall’Evento al Dato Archeologico: Il Sacco Del 410 Attraverso la Documentazione Archeologica.’ In The Sack of Rome in 410 AD: The Event, Its Context and Its Impact, edited by Johannes Lipps, Carlos Machado, and Philipp von Rummel, 35-39. Wiesbaden: Ludwig Reichert Verlag. A counterexample from a non-urban setting is the excavation at Montaccianico: Monti, Alessandro, and Elisa Pruno, eds. 2016. Tra Montaccianico e Firenze: gli Ubaldini e la Città. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Carrión Mena, Fernando, and Paulina Cepeda Pico. 2023. ‘Urbicide: An Unprecedented Methodological Entry in Urban Studies?’ in Urbicide: the Death of the City, edited by Fernando Carrión Mena and Paulina Cepeda Pico, 3-22. Cham: Springer, 8.

Coward, Martin. 2009. Urbicide: The Politics of Urban Destruction. London, New York: Routledge, 15, 128.

Ibid, for relevant bibliography. See also Delgadillo, Victor. 2023. ‘Epilogue. Remake Us from Ruins, Collective Memories and Dreams’ in Urbicide: the Death of the City, edited by Fernando Carrión Mena and Paulina Cepeda Pico, 3-22. Cham: Springer, 917-937, section 44.2.

Fachard, Sylvian, and Edward M. Harris. 2021. ‘Introduction: Destruction, Survival and Recovery in the Ancient Greek World.’ In The Destruction of Cities in the Ancient Greek World: Integrating the Archaeological and Literary Evidence, edited by Sylvian Fachard and Edward M. Harris, 1-33. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 18.

See for instance Coward, Martin. 2009. Op. cit.,127-128.

Nuzzo, Donatella. 2020. ‘Bari Dal Praetorium Bizantino Alla Cittadella Nicolaiana: Le Trasformazioni Di Un’area Urbana Alla Luce Delle Fonti Scritte e Della Documentazione Archeologica.’ In Oltre l’alto Medioevo: Etnie, Vicende, Culture Nella Puglia Normanno-Sveva, 203-225. Spoleto: Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, 206.

For these transformations: Musca, Giosuè. 1981. ‘Sviluppo Urbano e Vicende Politiche in Puglia. Il Caso Di Bari Medievale.’ In La Puglia Tra Medievo Ed Età Moderna: Città e Campagna, edited by Domenico Blasi, 14-49. Milan: Electa, 34-37.

Ivi, 38.

For an overview: Iorio, Raffaele. 1995. ‘L’urbanistica Medievale Di Bari Tra X e XIII Secolo.’ Archivio Storico Pugliese 48: 17-100; Palombella, Raffaella. 2014. ‘Modelli Abitativi e Transformazioni Del Tessuto Urbano a Bari Tra XI e XIV Secolo: Una Ricerca Multidisciplinare.’ In Case e Torri Medievali: Indagini Sui Centri Dell’Italia Meridionale e Insulare (Sec. XI-XV), Atti Del V Convegno, edited by Elisabetta De Minicis, IV:143-165. Rome: Edizioni Kappa.

Giuliani, Roberta. 2011. ‘L’edilizia Di XI Secolo Nella Puglia Centro-Settentrionale: Problemi e Prospettive Di Ricerca Alla Luce Di Alcuni Casi Di Studio’. In La Capitanata e l’Italia Meridionale Nel Secolo XI Da Bisanzio Ai Normanni, edited by Pasquale Favia and Giovanni De Venuto, 189-232. Bari: Edipuglia, 205.

Raffaella, Palombella. 2014. Op. cit., 154-155.

Falco of Benevento. 2012. ‘The Chronicle of Falco of Benevento’. In Roger II and the Creation of the Kingdom of Sicily: Selected Sources Translated and Annotated by Graham A. Loud, edited and translated by Graham A. Loud, 130-249. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 46.

Cited in Lavermicocca, Nino. 2017. Op. cit., 243.

Perfido, Paolo. 2008. ‘Una Parte Di Città. Assetti Urbani e Architettura Nella Bari Medievale: Il Vicinio Di S. Maria de Kiri Johannaci’. In Bari, Sotto La Città: Luoghi Della Memoria, edited by Maria Rosaria Depalo and Francesca Radina, 45-52. Bari: Mario Adda, 45.

Mucciarelli, Roberta. 2009. ‘Demolizioni Punitive: Guasti in Città.’ In La Costruzione della Città Comunale Italiana, Secoli XII-Inizio XIV, 293-330. Pistoia: Viella, 293ff.

Fredegar. 1888. ‘Fredegarius Scholasticus Chronicarum Libri IV’. MGH, SS, Rer. Merov. II, edited by Bruno Krusch. Hannover, 57.

Pertz, G.H., ed. 1866. Annales Ceccanenses. MGH SS 19. Hannover, entry y.1156.

Nitti di Vito, Francesco, ed. 1902. Le Pergamene Di S. Nicola Di Bari: Periodo Normanno (1075-1194). Codice Diplomatico Barese V. Bari: Società di storia patria per la Puglia [hencefort: CBD V], 114 (1157);116 (1158); 125, (1165).

CDB, V, frag. 16 (1160 ?) ; frag. 19-20 (1156-1165). Also: Iorio, Raffaele.1995. Op. cit., 24.

Delle Donne, Fulvio, ed. 2017. Breve Chronicon de Rebus Siculis, vol XII. RIS 3. Florence: Edizioni del Galluzzo.

Falcandus, Hugo. 1998. Op. cit., 73-74.

Riccardi, Ada. 2008. ‘I Progetti Di Riqualificazione Urbana: Le Indagini Archeologiche Nella Città Vecchia Di Bari’. In Bari, Sotto La Città: Luoghi Della Memoria, edited by Maria Rosaria Depalo and Francesca Radina, 93-98. Bari: Mario Adda editore, 97.

E.g.: CDB, V, frag. 16 (1160?), 119 (1161).

CDB, V, 114 (1157), 196.

Colafemmina, Cesare. 1975. ‘L’itinerario Pugliese Di Beniamino Da Tudela’. Archivio Storico Pugliese XXVIII: 81-100, 99.

Nitto de Rossi, G.B., and Francesco Nitti di Vito, eds. 1897. Le Pergamene Del Duomo Di Bari (952-1264). Codice Diplomatico Barese I [henceforth: CDB I]. Bari: Vecchi, 50, (11[6]7).

Tropeano, Placido Mario, ed. 1977. Codice Diplomatico Verginiano. Montevergine: Edizioni Padri Benedettini, XI, 1062; CDB, VI, 11.

For a couple of examples of house use: CDB, IV. No. 43, (1068), p. 85; Pellegrino, C., ed. 1724. Anonymi Barensis Chronicon (855-1149). RIS 5. Milan: Società Palatina, 156, MCXVIII. Ind. XI.

Falkenhausen, Vera von. 1984. ‘A Provincial Aristocracy: The Byzantine Provinces in Southern Italy (9th-11th Century)’. In The Byzantine Aristocracy IX to XIII Centuries, edited by Michael Angold, 211-235. Oxford: B.A.R., 224; Skinner, Patricia. 1998. ‘Room for Tension: Urban Life in Apulia in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries’. Papers of the British School at Rome 66: 159-176.

William of Apulia. The Deeds of Robert Guiscard. Translated by Graham A. Loud. Leeds Medieval History Texts in Translation Website. https://ims.leeds.ac.uk/archives/translations/ Book II, 27-28.

Iorio, Raffaele. 1995. Op. cit. 5.

CDB, V, Frag. 19-20 (1156-1165); 114 (1157), p. 196.

Iorio, Raffaele. 1995. Op. cit, 83ff.

CDB, I, 53 (1177).

Lavermicocca, Nino. 2017. Op. cit. 242-243.

Ivi, 249.

CDB, V, frag. 16 (1160?).

Cited in: Gabrieli, Andrea. 1899. Un Grande Statista Barese Del Secolo XII, Vittima Dell’odio Feudale. Trani: Vecchi, 27-33; cfr: Panarelli, Francesco. 2011. ‘Le Origine Del Monastero Femminile Delle SS. Lucia e Agata a Matera e La Famiglia Di Maione Di Bari’. In ArNoS, 3:19-32, 29-30.

Panarelli, Francesco. 2011. Op. cit., 30; Falcandus, Hugo. 1998. Op. cit., 77.

See the contemporary account of John Kinnamos, calling it a ‘fortress’: John Kinnamos. 1976. Deeds of John and Manuel Comnenus. Translated by Charles M. Brand. New York: Columbia University Press, 110.

Nuzzo, Donatella. 2020. Op. cit., 216.

Delle Donne, Fulvio. 2017. Op. cit., XII, 57-61.

See for instance Tusculum: Beolchini, Valeria. 2006. Tusculum II. Tuscolo, Una Roccaforte Dinastica a Controllo Della Valle Latina: Fonti Storiche e Dati Archeologici. Rome: L'Erma di Bretschneider.

Lavermicocca, Nino. 2017. Op. cit., 246.

Delle Donne, Fulvio. 2017. Op. cit., XII, 57-61.

CDB, I, 50, (11[6]7).

Massa, Teodoro. 1903. Le Consuetudini Della Città Di Bari: Studi e Ricerche. Bari: Vecchi; Copeta, Clara. 2011. ‘Bari: Una Ciudad Multiétnica En La Edad Media’. Plurimondi 9: 139-164, 111.

Andrea da Bari and Sparano da Bari. 1860. Il Testo Delle Consuetudini Baresi. Edited and translated by Giulio Petroni. Naples: Stamperia del Fibreno, 42; 54-56; 106; 140-141; 148, et al.

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Lorenzo Mingardi (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Lorenzo Grieco

Tom Avermaete Leonardo Zuccaro Marchi

Jade Berger Adrien Marchand Hugo Steinmetz