The architecture of the Second Reconstruction in France emerged from a national policy aimed at rebuilding the country after the Second World War. The Saint-Dié-des-Vosges district is characterized by two specific features: physically, a highly dispersed housing layout in a predominantly rural mountainous region; and historically, the context of a brutal German retreat known as the “scorched earth” strategy.

This article examines the role of remembering these destructions in the Reconstruction policy at the time and in the recent preservation of the reconstructed buildings. Amid oblivion, denial, and the choice to remember, the memory of the destruction tends to fade away.

Our paper is based on architectural and historical research conducted by four architect-teachers since July 2018 as part of a partnership between the LHAC and the agglomeration of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, France. The study focused on post-World War II housing and public buildings involving a comprehensive examination of departmental archives, municipal archives of Saint-Dié, and those of six rural municipalities: Anould, Ban-sur-Meurthe, Gerbépal, Jeanménil, Saint-Léonard, and Saulcy-sur-Meurthe1.

The architecture of the Second Reconstruction in France was shaped by a national policy aimed at rebuilding the country after the Second World War2. The district of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges is marked by two distinctive features: physically, a highly dispersed housing layout in a predominantly rural and mountaineer area; historically, the context of a brutal German retreat known as the “scorched earth” strategy.

This region has received much less attention than other areas of French reconstruction, such as the north or west of France, and specific cities like Le Havre, Royan, or Tours. However, the Vosges, and more specifically the arrondissement of Saint-Dié, presents a unique case with valuable lessons to offer. Firstly, the diversity in the scale of the reconstructed municipality, ranging from hamlets to dispersed villages, through the town of Saint-Dié, resulted in a local adaptation of the methodology proposed by the Ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme. This adaptation fostered new stakeholder dynamics and greater freedom for the architects responsible for reconstruction in small communities3. Secondly, the remote nature of the communities affected by the disaster facilitated the reuse of local construction techniques to rebuild the area4.

On the one hand, the extensive use of local materials and traditional forms has ensured a certain continuity in the architectural identity of these villages. Thus, the material identity of the studied villages does not seem to have been affected by the systematic physical destruction of farms, dwellings, and communal buildings. On the other hand, the scars left by the events, despite their tragic nature, appear to be gradually fading from the collective memory. We argue that this is due to the gradual disappearance of traces of the destruction in architectural forms that no longer exhibit ruins and have not yet been the subject of any cultural interpretation.The absence of a memorial specifically dedicated to the memory of these events may reflect the trauma of a destruction that was not only rapid but also pointless in strictly strategic terms. This specific absence may also highlight the challenge of representing a painful memory in physical space.

To what extent does the process of turning reconstructed buildings into heritage sites tend to prioritize the preservation of physical artefacts over the intangible traces of destruction?

This historical research draws on a large corpus of archives to provide a detailed analysis of the area under study. It also incorporates authors and sources from other disciplines, particularly sociology and philosophy, to characterize complex concepts such as memory and identity. Beyond proposing a multidisciplinary analysis, the aim here is to interrogate the built heritage as a medium for memorialization.

After analyzing the devastation caused by the scorched earth strategy in this region, we will examine how the reconstruction facilitated the preservation of the memory of the events. Subsequently, we will shift our focus on the current heritage policy regarding these reconstructed objects and explore whether the physical remnants of the reconstruction take precedence over the intangible memories of the destruction.

At the end of Second World War, European countries were affected to varying degrees. In Great Britain, 4,700,000 buildings were damaged, with 200,000 of them being totally destroyed5. In the Netherlands, 82,000 homes were destroyed and 50,000 were damaged. However, it was certainly in Germany that the destruction was most severe. A total of 2,340,000 homes were completely destroyed, constituting 20% of the 1939 stock, while an additional 2,500,000 were partially damaged6.

Following the conclusion of World War II, France was ravaged by four years of occupation, spoliation, and bombing. Approximately 600,000 people died directly because of the war, and an additional 530,000 died from its consequences. The entire region is affected by the destruction: 74 departments are involved, with 420,000 residential buildings that suffered complete damage, and 1,900,000 partially damaged. Additionally, 5,000 farms are destroyed or rendered unusable, along with industrial facilities and critical infrastructure such as bridges, railroads, roads, docks, and canals, leaving behind a lunar and ruined landscape7.

More specifically, the Vosges area, a predominantly rural and semi-mountainous department of the Lorraine region, suffered extensive destruction during the Second World War. In November 1944, the Germans executed a retreat by burning the cities and villages they abandoned, following a policy known as the “scorched earth” strategy8. The district of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges was the most severely affected. The Ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme (MRU) reported 4,600 destroyed buildings and 8,900 partially destroyed buildings out of a total of 30,000 in 19529.

Following the Allied landings in Normandy on June 6, 1944, the German army stationed in the Vosges was ordered to establish a defensive position to the west known as the “Schutzwall West.” The Vosges massif became the site of daily confrontations between the German armed forces and the local resistance, which consisted of numerous maquis. The German operation “Waldfest,” launched in September 194410, initially aimed to suppress local resistance movements, evacuate the civilian population, and destroy towns and villages. Resistance fighters were deported to Germany as forced laborers, local populations were displaced, and goods such as machinery, livestock, and food were requisitioned11.

In Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, the destruction began in September 1944 with Allied bombing raids. From November 9 onwards, Nazi troops ordered the residents to evacuate the town. The fire started on November 14, 1944, and lasted for five days12.

Saint-Dié est durement meurtrie et près de la moitié de ses habitants, soit 10 000 personnes, se trouvent sinistrés ; plus de 1 500 immeubles sont détruits, faisant de cette ville la plus endommagée du département, devant Gérardmer, La Bresse et Épinal13.

Some iconic buildings, such as the cathedral, were demolished with dynamite (figg.1 and 2).

Certainly, the case of Saint-Dié and its surrounding area is not unique. The city centers of numerous French cities were bombed during the conflict. The case of Brest has been studied by Le Couedic (1948-…), who demonstrates that the reconstruction project results from a “highly liberal interpretation of certain features of the old city14” with the goal of maintaining a subtle continuity between the remnants of the historic city and the modern reconstruction project. In this way, the adaptation of roads to accommodate the demands of automobiles, the strategic distribution of activities and people in optimal.

Cities in the northern part of France, such as Douai, Valenciennes, and Lille, share similarities with the Saint-Dié conurbation, as they were extensively destroyed in the aftermath of the Second World War. In Douai, approximately 830 buildings, or 11% of the housing stock, were completely destroyed, and 4,000 were partially damaged. The Lille region was heavily affected by the strategic bombing of rail hubs and industries in 194415. In Lens, destruction was widespread, with an estimated 800 buildings completely devastated, 900 were badly damaged, and 1,500 were immediately repairable16.

In mid-November 1944, in response to the rapid advance of Allied troops, Nazi forces set fire to nine villages in the Vosges mountains to hinder the enemy from accessing supplies17. Despite focusing on town and village centers, the destruction was not limited to strategic targets. After ordering residents to evacuate, the Germans destroyed all public and residential buildings, as well as all means of production (industrial and craft facilities) and transport (bridges and infrastructure).

The scorched earth policy, initially a military strategy to facilitate the retreat of German troops, also functions as a symbolic act of violence intended to weaken occupied populations by erasing all traces of the past. Pierre Delagoutte (1934-2000) reports the testimony of a resident who, upon returning to the village after being evacuated, painfully describes the discovery of the ruins:

Le lendemain matin vers les huit heures je viens du Préxetin au Village. Tout est brûlé ! Devant cet amas de ruines qui sentait le chaud je ne puis contenir mon émotion. […] Il y a des soldats américains au village. On les entend plutôt remuer de la ferraille ou des caisses que de les voir. Ils cherchent à s’installer à peu près dans les caves des maisons démolies18.

The destructions left behind a painful memory, serving as a poignant reminder of the assertion of Nazi power over an occupied territory engaged in resistance. As noted by French geographer Vincent Veschambres (1966-…), demolition is motivated both economically and ideologically19, as it always represents20.

Considered one of the greatest tragedies in contemporary local history, the German destruction in the Vosges remained a taboo for many years. The memory of the Nazi sacking was suppressed by residents and institutions in favour of a patriotic narrative centered on the memory of the Libération (e.g., through commemorating dates and honoring the memories of those involved).

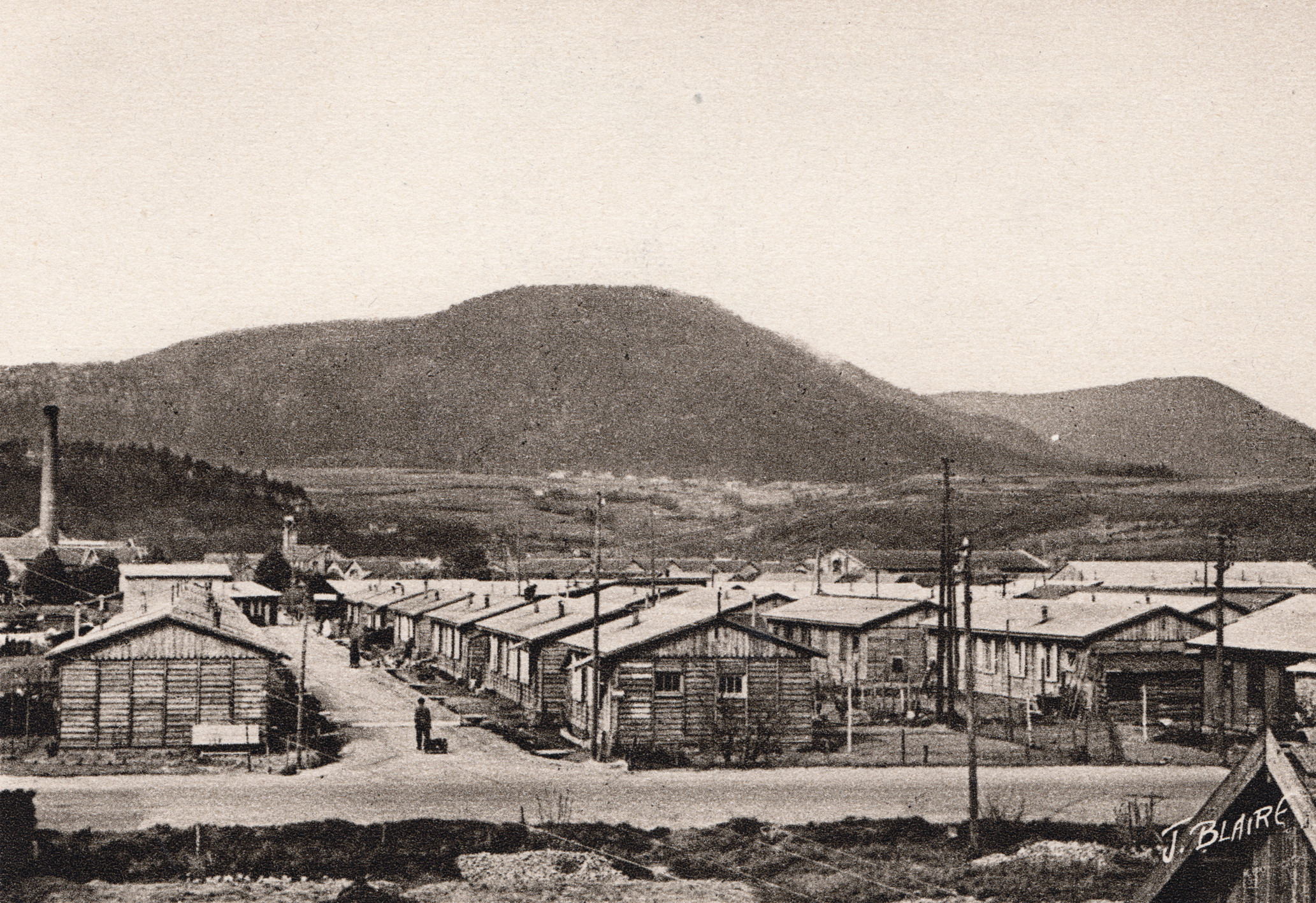

However, as the war ended, the municipalities in the Saint-Dié district were characterized by a new landscape of ruins, vacant lots, and piles of rubble. The initial efforts involved clearing traffic routes, demolishing ruins, and relocating disaster victims21. A provisional city was established: the debris was sorted and carefully arranged according to the original plot structure, to recreate the vanished urban layout (fig. 3). Camps of wooden barracks were slowly constructed on the outskirts of the devastated areas (fig. 4).

The Second Reconstruction era has sparked a wealth of literature, ranging from the ground-breaking research of Kopp (1915-1990), Boucher (19XX-…), and Pauly (1958-…)22, which highlights the State’s role in the reconstruction process, to more recent studies by Palant-Frapier (1976-…), Gourbin (1962-…), and Buffler (1981-…)23, who scrutinize the architectural intervention and heritage protection of buildings from this period.

Historian Joseph Abram’s (1951-…) work offers an initial overview of this crucial period in the history of French architecture. Abram reflects on the debacle and the Occupation, followed by the decade or so after the Liberation. The historian demonstrates how an original technocratic apparatus was established in 1940 and how a new generation of professionals attempted to address the new “problems of modernity24”.

The European cases were examined in the publication edited by Barjot (1950-…), Baudouï (1958-…), and Voldman (1946-…). The publication highlights the surprising nature of reconstruction, particularly noting that the anticipated stagnation of European countries did not materialize. Instead, the ruins were cleared, the cities rebuilt, and the states reformed25. In this context, Kuisel’s (1935-…) work has demonstrated how “the Liberation and the post-war years represent a significant shift in the economic structure of twentieth-century France26”.

The Second Reconstruction is a significant period in the history of architecture in France27. The French government established a new administration28 entirely dedicated to rebuilding France from the ruins: the aforementioned MRU (Ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme). Initially, the primary operationsinvolved clearing mines and rubble from the affected areas, followed by rebuilding through the approval of architects, organization of building sites, and planning of programs. The process lasted about ten years from approximately 1945 to 195529, following the Libération.

The architects involved in the process adhered to the modern principles of the “ville radieuse”, such as protection against humidity and inclement weather, sunlight and ventilation, running water, indoor toilets, electricity, central heating, etc30. The urban renewal project includes plot-based regulation and consolidation, the enlargement of urban blocks, the straightening and widening of streets, and the opening of the built-up area31. This occurred irrespective of whether the buildings were reconstructed identically or in a modern style.

In response to the scale of the destruction, the MRU harbors significant ambitions for Saint-Dié’s district.Georges Michau (1895-1954) was specially appointed as the chief architect to lead the reconstruction.Unfortunately, we do not have extensive records of Michau’s32, but numerous traces of his activities in Vosges have been discovered. Like all chief architects33, his role was to coordinate the reconstruction on a territorial scale, supervise the operating architects appointed by the MRU, and approve their projects34.

For each disaster-affected commune, the government appointed an architect-urban planner to create the primary graphic documents and develop the reconstruction and development plan (PRA). In the Vosges region, the PRA for Saint-Dié35 was assigned to Jacques André36 (1904-1985), an architect from Nancy, while the remaining affected villages were grouped based on their geographical location. For example, the five disaster-stricken rural communities in the Meurthe valley were assigned to Parisian architect François Boleslas de Jankowski (1889-1972)37. For each development plan implemented between 1945 and 1946, the architect designed a memorial to commemorate the human losses caused by the Second World War. These war memorials serve as structuring elements of the new town centers. Often located near the local church and town hall, as in Saint-Léonard and Anould, these structures shape the public space by dominating the village’s main square. The memories associated with these monuments are so strong that they can sometimes create a new sense of centrality. This is the case in Saulcy-sur-Meurthe, where the war memorial is integrated into a new rectangular square and serves as a focal point for a new district called “Le Village” (fig.5).

As historian Antoine Prost (1933-…) has demonstrated, the placement of the war memorial in the 20th century was a highly strategic and symbolic decision, progressively defining the village’s space. Initially installed in the church square, which could also serve as the forecourt of the town hall, the war memorial was always erected in the most bustling location in the village.

Les monuments aux morts tirent d’abord leur signification de leur localisation dans un espace qui n’est pas neutre. Les dresser dans la cour de l’école, sur la place de la mairie, devant l’église, dans le cimetière, ou au plus passant des carrefours n’est pas un choix innocent38.

In the case of reconstructed villages, the memorial is situated in a strategic area, as are all war memorials. It serves to convey the memory of human losses and commemorates victory. Moreover, the memorial can play a role in restructuring the public space of the town center during the reconstruction process. It becomes a compositional element in the design of new PRAs. Occasionally free-standing and rarely rebuilt on the site of the now-defunct First World War memorial, it becomes part of a square, landscaping, or urban development. It offers a “rural urbanism” that is entirely dedicated to remembrance.

These early monuments interest us for two reasons. Firstly, they were designed as a continuation of the memorials built after the First World War. They quantify the human casualties caused by the war and list the names of those who perished. The Saulcy war memorial illustrates this continuity through its composition: it symmetrically contrasts the losses of the First World War with those of the Second (fig.6). Secondly, these commemorative sites help propagate a patriotic memory, specifically the memory of national victory and the heroic deeds of soldiers who fell in battle for France. Lastly, these monuments aim to facilitate the act of mourning by providing a place for reflection that embodies the grief shared by the entire population.

Unlike human losses, there are no memorial sites dedicated to transmitting the memory of the physical destruction of the vanished urban fabric. However, architects and urban planners of the Reconstruction are integrating urban remnants into new PRAs. To preserve the identity of each urban area, these plans respect the original municipality’s morphology and the design of certain roads. The vast majority of PRAs also advocate for the reconstruction of symbolic and religious sites in their original locations.

These plans illustrate the desire to establish connections between the disappeared state and the current state, as well as to leave a “mark” as Veschambre describes it. Here, the trace of a preserved road corresponds to a

signature intentionnelle: elle est pensée et produite pour rendre visible une personne, un groupe, une institution, pour constituer le support d’une identification (individuelle ou plus généralement collective), et pour représenter au final un attribut l’acteur ou du groupe en question39.

The path that once served as a road in the 18th century or the site of a church is now reimagined by the architect-urban planner, who incorporates their own unique vision into it.

Georges Michau holds a specific opinion about the architectural style to be imposed on the Vosges territory.He aims to implement a standardized architecture, following the “MRU-style” characterised by architectural historian Danièle Voldman as “rigoureux et reproductible40”. In Saint-Dié, Michau directed the drafts toward a modern and industrialized style, incorporating concrete frames, modern materials, and serial construction.

During the Reconstruction, some historical materials of architecture were rediscovered due to energy shortages: adobe, stone, ceramic and structural gypsum being among them. French architect Pol Abraham (1891-1966) proposed an update of the ancient techniques by combining historical skills with mechanical tools trough the normalization of the construction sector41. This is what Marcel Lods (1891-1978) refers to as “traditionnel évolué.” The “traditionnel évolué” consisted of modernizing and streamlining established construction techniques, processes, tools, and materials42. It served as a middle ground between traditional construction methods (typically used for renovating historic monuments) and fully mechanized prefabrication (used for producing standard residential buildings). It was in this trend that the essence of the Second Reconstruction’s architecture was embodied43.

For Abraham, this conception of heavy masonry is key to the permanence of architecture: he can’t accept that a building can be constructed like an industrialized car, for example44.

In the case of Saint-Dié’s district, this conception of “traditionnel évolué”45 is characterized by using some local building materials. The Vosges sandstone (“grès rose”) is probably the most common and applied in various ways: as an apparatus in the substructure of common buildings or in external elevation of the uncommon ones, as well as rubble stones covered with lime or cement coating. However, the Reconstruction does not only restore the ancient buildings with those historical materials. Some of exogenous ones are used in specific purposes: steel for carpentry, concrete for basements, lintel, columns, and beams, for example. In fact, architects have no choice to manage with available materials (fig. 7).

This differs from other French regions. In the Hautes-Alpes region, for example, approximately 60 rural villages were bombed in 1944, and industrialized materials were employed instead of local materials, causing harm to the local economy. For instance, cinder blocks and concrete were extensively used for load-bearing masonry, while stone was only used for facing. Window frames were crafted from prefabricated concrete elements, and roofing materials exhibited greater diversity, with mechanical terracotta tiles replacing traditional canal tiles, and corrugated iron supplanting wooden shingles46.

The “traditionnel évolué” style is prominently reflected in the overall appearance of buildings. In the urban area of Saint-Dié, as well as in the rural areas of the Vercors, the reinterpretation of reconstructed buildings is evident in their volumetric design. The clustering of previously scattered buildings results in a change of scale47 compared to traditional constructions, and specific functions of the farmhouse are much more clearly defined. In the villages under examination, farmhouses are consistently composed of three sections: one for the dwelling, another for the barn, and the last for the stable.

In addition to the material approach, the architects responsible for the reconstruction of each individual building employed a variety of architectural vocabularies to preserve landmarks for the local population and blend in with the Vosges mountainous landscape.

Indeed, the central administration adopted an intermediate solution between identical reconstruction and a complete eradication of the past. It aimed to avoid both the reconstitution of destroyed cities and the creation of cities designed according to a theoretical scheme that disregarded the past. Furthermore, it sought to avoid pitting materials against each other, choosing between architectural pastiche and the dominance of concrete48. This approach encourages architects to seek new solutions to the problems posed by destruction, while also considering the traditional way of life. Many reconstructed towns draw inspiration from ancient plans, preserving the logic of the island through buildings constructed in line with the streets.

This approach, described by some researchers as “moderate modernism,” provides further evidence of the particular attention paid by rebuilding architects to reinvesting existing traces and preserving the material and architectural history within these reconstructed communities:

La divergence entre régionalistes et modernes a aussi créé de nouvelles formes architecturales synthétisant les avantages des deux conceptions, tout en tentant d’en limiter les désagréments. Cette tendance que l’on peut qualifier “de modernisme modéré” insiste sur la nécessité de reconstruire selon des normes contemporaines (hygiène, confort, salubrité, industrialisation, circulation...) tout en préservant les repères des populations, leur mémoire, leur territoire, leur culture par une intégration forte des constructions dans le paysage local49.

The focus of heritage protection underwent a gradual shift, moving from the conventional emphasis on the object itself, as defined by the canons of art history, to encompass the immediate environment of the protected object (including its surroundings and context), and eventually expanded to include natural landscapes by 1970. The preservation of historic monuments broadened in its scope, now extending beyond prestigious buildings, to encompass everyday structures that bear witness50 to their cultural and technical context (e.g., mailman Cheval’s famous Palais ideal, 1879-1912), as well as various domestic or industrial buildings.

In France, this protection is accompanied by a significant increase in heritage classifications and preservation. In 2007, there were over 43,000 protected monuments and an average of 140 new classifications annually. This surge in classifications has been paralleled by an abundance of literature since the early 1980s51, including symposia, theses, articles, journals, and books.

Old town centers are receiving increasing attention from public authorities. The heritage value of buildings and town planning is recognised by various stakeholders, including property vendors, elected representatives, and residents. This value is the result of the struggles that began during the Reconstruction period, when the issue of renewing unhealthy housing estates in historic town centers arose. These struggles led to the introduction of several national bills aimed at protecting and organizing the city’s heritage and development. As a result, it became apparent that the morphology of old buildings was fixed52.

Early research on the architecture of the Second Reconstruction period began in France in the 1990s53. Numerous targeted studies have enabled the construction of an initial inventory of architectural works in certain regions (primarily North and West France) and the characterization of the urban developments inherited from this period.

At the local level in the Vosges region, architectural historians are studying the reconstruction of Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, focusing on the reconstruction plan proposed by Le Corbusier (1887-1965). This plan resulted in a well-known conflict with the town-planning architect Jacques André54, who was commissioned by the MRU. The legacy of the Second Reconstruction in the Vosges did not become a subject of research and a heritage to be preserved and promoted until the 2010s.

This period also corresponds to the first studies conducted by the Inventaire régional du Grand Est. While some thematic surveys focused on specific geographical areas (e.g., rural architecture in the Hautes-Vosges and reconstructed farms55 or churches), a few towns were the subject of comprehensive studies, such as the small towns of Gérardmer or Saint-Dié-des-Vosges, or the reconstructed village of Corcieux56.

The growing interest in the history of the Second Reconstruction explains the robust heritage and cultural policy implemented by the Saint-Dié community of communes from 2013 onwards. The first step in this policy was the awarding of the Architecture Contemporaine Remarquable (ACR) label to the rebuilt city center of Saint-Dié in 2015. The UNESCO World Heritage listing of Le Corbusier’s Usine verte in 2016 also signifies the beginning of a new initiative: the development of a regulatory framework for the protection of a territory (referred to as SPR, for site patrimonial remarquable). The reconstructed village of Corcieux will be fully ACR-certified in 2016, along with several other buildings dating from the same period.

In addition to these protection initiatives, between 2016 and 2021, additional efforts were made to raise awareness about the architecture of the Second Reconstruction period, creating opportunities to engage with local communities. The local authority, through exhibitions at the Saint-Dié Museum, publications, mediation workshops, and guided tours is committed to promoting a local heritage that has been overlooked and underappreciated by the public.

Residents do not fully appreciate the historical value of the buildings constructed during the Reconstruction period. This is partly due to the complexity of the buildings, which may be difficult to understand without formal architectural education. Additionally, their everyday use may overshadow their significance as monumental structures.

Simultaneously, the population is aging, and the acquisition of these historical buildings by a younger demographic is accompanied by a desire to enhance housing. As a matter of fact, some of the housing that met the comfort standards of the 1950s and 1960s may be seen as quite outdated today. The renovation and modification of these houses (e.g., through external insulation or extensions, figg. 8a and 8b) also affect their authenticity and the historical value derived from the cognitive access to their historical context.

Today, temporality is shifting: the witnesses of demolitions or reconstruction are disappearing. Reconstructed buildings have become a common sight, unrecognizable to most residents. The memory of the "scorched earth" is fading across generations. No intentional monument has been created to convey this painful memory and commemorate the destruction. Only a few reconstructed buildings remain to bear witness to the devastation on the territory, but they are not considered heritage sites.

The historical value of the reconstructed buildings is not always visually perceptible. When standing in front of an object, we can only perceive its formal properties, such as construction techniques, materials, and typology.However, the cultural heritage of the Second Reconstruction is also characterized by relational properties.When we refer to “relational properties,” we are talking about the imperceptible properties of the built object that play a part in its historical evaluation. These properties include having a specific author, being constructed at a particular time, and being the result of a unique policy or historical event. One way to comprehend the significance of non-perceptual properties in the evaluation of cultural heritage is presented by American philosopher Robert Audi (1941-…), who distinguishes these types of properties as artistic. He explains that these properties, such as “being painted by Rembrandt and being original in the relevant genre, a property works in any artistic medium are eligible to have. The former (on my view) does not bear on strictly aesthetic properties, as opposed to what we might call artistic properties57”. The relevant artistic properties of the Reconstruction heritage in Vosges are, for our case, those of being authentically built during the Reconstruction period.

Another way to distinguish these properties is by considering their role in characterizing the genesis of the built object. The fact that a building has been conceived by certain people, in certain conditions, reflects features of the object that no direct experience of it can account for, as the American art philosopher Monroe Beardsley (1915-1985) puts it:

I call a reason Genetic if it refers to something existing before the work itself, to the manner in which it was produced, or its connection with antecedent objects and psychological states58.

These properties include being built through a decision process established by the MRU or being the result of heated debates between chief architect Michau and operating architect Jankowski, as seen in the case of Saulcy’s public buildings among others59.

A third way of using non-perceptual properties in evaluation is to consider the relations an object may have with other objects. The reconstructed architectural objects in St-Dié, being constructed within the framework of a national policy and specifically using a standardized local building method, are characterised by a collective status. This unique axiological characteristic is referred to as “regime de communauté”60 by French art sociologist Natalie Heinich (1955-…).

All these accounts of non-perceptual properties explain the challenge of extracting the historical value of our objects. This challenge contributes to the modern transformation of the concept of heritage, shifting it from an aesthetic and perceptual focus to a cognitive and non-perceptual one. According to the French geographer Vincent Veschambre,

[...] la conception du patrimoine a notablement évolué durant ces quarante dernières années : elle est passée d’une vision classique, esthétisante, du type histoire de l’art à une vision beaucoup plus ethnologique, voire sociologique61.

Mais cette évolution ne signifie pas pour autant que la conception classique, monumentale a disparu, notamment chez les acteurs de la protection du patrimoine. En cette conception ethnologique ne s’est pas traduite de manière spectaculaire en terme [sic] de protection62.

In Europe, everyday architecture constitutes 70% of the construction industry, with a significant portion63. Thus, while the memory of Reconstruction is preserved by the buildings before us, the painful memory of the Destruction remains elusive in their sole experience.

Collective memory is a constantly evolving social construct:

La mémoire ne doit pas être confondue avec la “vérité” du souvenir : c’est une logique sociale, une structure qui donne du sens au passé. Et ces structures ne sont jamais le reflet du réel, mais justement, des constructions [...]64.

L’individu évoque ses souvenirs en s’aidant des cadres de la mémoire sociale. En d’autres termes les divers groupes en lesquels se décomposent la société sont capables à chaque instant de reconstruire leur passé65.

Reconstructing memory is akin to distorting historical truth. French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs (1877-1945) claims that collective memory is a social construct created to fulfill human needs: the need for social unity and the need for continuity. As a result, society tends to erase from its memory

tout ce qui pourrait séparer les individus, éloigner les groupes des uns des autres, et qu'à chaque époque elle remanie ses souvenirs de manière à les mettre en accord avec les conditions variables de son équilibre66.

The formation of collective memory is rational and reconstructed based on the “social frameworks” essential for recognizing and situating memories. Social frameworks consist of language, time, space, and experience.

As previously mentioned, the memory of the Second World War in the Vosges region does not necessarily restore the truth of the events following the Liberation, but it does offer consolation. The issue is more practical than epistemological, as it involves commemorating Victory and justifying loss. It also serves to encourage the mourning process of the affected population and maintain social cohesion. In the early stages, memory and history were in competition with each other. French philosopher Paul Ricoeur (1913-2005) highlights “l’étrangeté de l’histoire, l'interminable compétition entre le vœu de la fidélité de la mémoire et la recherche de la vérité en histoire67”. While remembrance aims to unite people and commemorate the national Victory, the historical account points to the unique nature of the Vosges region and its destruction, which cannot be equated with the rest of France. The pursuit of historical truth necessitates historians and architects to emphasize this painful memory and remember the specific impact of the devastation caused by the scorched-earth policy.

The tension between history and memory is at the heart of the actual patrimonialization policies aimed at preserving the last remaining witnesses of these dramatic times viz., the rebuilt buildings.

The heritage policies implemented over the past two decades have selected and protected rebuilt complexes as well as isolated buildings, emphasizing the reconstruction policy. The purpose of these examples is to document the new urban planning and architectural systems implemented by the architects hired by the MRU, offering insight into the methods used to rebuild quickly while integrating modern principles. This new heritage also offers an opportunity to explore the mass production and standardization that took place in the region during this period.

However, the painful memory of the destruction that led to this heritage remains the most difficult to convey. Out of habit or convenience, it is rarely addressed in regulatory protection tools such as SPRs or ACR labels. These protection and safeguard perimeters precisely define the reconstructed buildings that are most emblematic of the reconstruction policy. These tools are used to manage an existing material heritage that is evolving in nature.

This case study of the Saint-Dié-des-Vosges district is a perfect illustration of the challenge of creating space for multiple memories, especially those that are painful. In France, the memory of the destruction caused by the Second World War is primarily preserved through sanctuaries transformed into sites of martyrdom, such as the devastated village of Oradour-sur-Glane. But is it necessary to suppress the destruction in reconstructed areas? Minimizing destruction as part of the heritage process tends to undermine the primary purpose of preserving these buildings: they are rebuilt because they have been damaged or destroyed. Couldn’t the policy of heritage preservation facilitate the transmission of memories?

The question persists: how can we preserve the intangible identity of this heritage? Several mediation tools, such as panels, exhibitions, publications, etc., have been designed to convey specific historical truths and intangible values. They remind us of the context in which these buildings were created and the people who built them.

Although necessary, this process of preserving heritage is gradually supplanting the painful memory of destruction and reconstruction with the memory of the state’s rebuilding efforts. For example, temporary settlements and barracks have vanished from the landscape, and the few remaining examples are not afforded protection. No images depicting the destruction or ruins are to be found within the perimeter of a particular memorial site.

Patrimonialization, while still in progress, seems to entail a significant selection of memorials. In the absence of effective means of transmitting local memory of the destruction, the very act of patrimonialization tends to cause this specific memory of the fading into oblivion.

The opening section of this article establishes the context for our study. By recalling the devastation caused by the Second World War in France and the Vosges, and by emphasizing the systematic policy of “scorched earth” following the German retreat, we have demonstrated that destruction embodies a “painful memory” driven by both economic and ideological motives.

By situating the reconstruction of Saint-Dié within a broader comparative literature, we were able to highlight its unique characteristics and parallels with other national and European cases. We have also demonstrated the role played by chief architects in the process of “reasonable modernization” of rebuilt centers, particularly in emphasizing the memory of the war through the construction of war memorials. War memorials play a central role in reconstruction plans, both in a physical and symbolic sense.

The third part of the article, which combines historical and philosophical methods, enables us to discuss the process of turning these everyday architectures into cultural heritage.

By showcasing the architectural significance of these commonplace buildings and engaging the residents of the reconstructed villages, we argue that the memory of reconstruction is preserved in the authenticity of these structures. As historian Rémi Baudouï points out,

[...] le cycle de la destruction est aux origines d’un traumatisme qui obère les facultés de penser la ville détruite comme produit de l’instant de guerre, circonscrit entre passé et futur. À cette vision de la déchirure du sinistré, se superpose une vision politique du dépassement de la revendication locale au nom de l’idéal politique de l’après-guerre. Le Silence de la mémoire signale la nécessité de dépasser l’histoire du lieu par l’idéal de modernisation défini comme le ciment pour restaurer la nation68.

The fourth and final section emphasizes the significance of preserving the buildings that were reconstructed to maintain a collective memory of the damage and the local efforts made. This position involves an operational approach and the recommendation of architectural solutions that can be partially implemented as part of an improvement project in collaboration with local stakeholders69. The deliberate preservation of reconstructed architecture is a key aspect of a well-considered design approach, which contributes to the success of the architectural project and adds value to the area.

notes

A first phase (2018–2019) allowed us to report on the specificities of the reconstructed buildings, to build an important historical database, and to share our results through a travelling exhibition open to the public.

Kopp, Anatole, Frédérique Boucher, and Danièle Pauly. 1982. L’architecture de la Reconstruction en France, 1945-1953. Paris: Le Moniteur; Barjot, Dominique, Rémi Baudouï, and Danièle Voldman. eds. 1995. Les Reconstructions en Europe (1945–1949). Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe; Dautry, Raoul. 1945. La Reconstruction de la France. Paris: Service-Echos; Voldman, Danièle. 1997. La Reconstruction des villes françaises de 1940 à 1954: histoire d’une politique. Paris: L’Harmattan.

As an example, we can mention the specific role assigned to the “communal architect” in the reconstruction of the villages in the arrondissement of Saint-Dié. Appointed by the municipal council of each village, rather than by the Ministry, the municipal architect was officially responsible for reconstructing municipal buildings under the supervision of the chief architect of the arrondissement. However, the architect's responsibilities could vary, including creating plans for communal facilities, urban development plans, and town center drawings, coordinating architects hired for projects in the community, and providing advice to the town council.

Steinmetz, Hugo, et. al. 2023. “Leçons constructives de la Seconde Reconstruction”. In Architecture et urbanisme de la Seconde Reconstruction en France. Nouvelles recherches, nouveaux regards, nouveaux enjeux, edited by Christel Palant-Frapier and Camille Bidaux. Mont-Saint-Aignan: Presses Universitaires de Rouen et du Havre (to be published).

Guerrand, Roger-Henri. 1992. Une Europe en construction. Deux siècles d’habitat social en Europe. Paris: La Découverte, 179.

Ivi, 182-183.

Berstein, Serge, and Pierre Milza. 2010. Histoire de la France au XXe siècle. Tome II. 1930-1958. Paris: Perrin, 456.

Regarding the prioritization of cities as targets for destruction, please see: Voldman, Danièle. 1997. Op. cit., 70 sq.

AD 88, fonds de la Reconstruction dans les Vosges, 1815W1965, Ministère de la Reconstruction et de l’Urbanisme, Destructions par arrondissement, Vosges, janvier 1952.

For information on the fighting during the Liberation of Eastern France in 1944, see: Drévillon, Hervé and Olivier Wieviorka. eds. 2018. Histoire militaire de la France. Tome II. De 1870 à nos jours. Paris: Perrin, 468-475.

Delagoutte, Pierre. 1987. Gerbépal Mon Village. Rambervillers: Holveck, 73.

Thilleul, Karine. 2018. La Seconde Reconstruction à Saint-Dié-Des-Vosges. Débats Urbains, Patrimoine Humain. Paris: Nouvelles éditions Place, 10.

Ibid.

Le Couedic, Daniel. 1983. “Brest, Une reconstruction autre”. In Les trois Reconstructions : 1919-1940-1945. Volume 3. 1940-1960. Industrialisation : Reconstruction et exportation de la société française, edited by Jean-Pierre Épron, 27-32. Paris: Institut Français d’Architecture.

Roger, Philippe. 2017. “Douai et Lille de la Seconde Reconstruction à l’aménagement urbain”. In Reconstruire le Nord-Pas-de-Calais après la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1944-1958), edited by Michel-Pierre Chélini and Philippe Roger, 284 sq. Villeneuve-d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

Lefevre, Christophe. 2017. “La Reconstruction de Lens (1944-1946)”. In Reconstruire le Nord-Pas-de-Calais après la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1944-1958), edited by Michel-Pierre Chélini and Philippe Roger, 303. Villeneuve-d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

Grand Est et al. 2016. Corcieux, Un bourg Reconstruit, Alsace Champagne-Ardenne Lorraine. Lyon: Lieux dits, 12.

Delagoutte, Pierre. 1987. Op. cit., 77.

Veschambre, Vincent. 2008. Traces et mémoires urbaines : enjeux sociaux de la patrimonialisation et de la démolition. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 115.

Ibid.

Cupers, Kenny. 2018. La banlieue, un projet social. Ambitions d’une politique urbaine, 1945-1975. Paris: Parenthèses, 43 sq.

Kopp, Anatole, Frédérique Boucher, and Danièle Pauly. 1982. Op. cit.

Buffler, Éléonore, Patrice Gourbin, and Christel Palant-Frapier. 2020. Protéger, valoriser, intervenir sur l’architecture et l’urbanisme de la Seconde Reconstruction en France. Actualité et avenir d’un patrimoine méconnu. Gand: Snoeck.

Abram, Joseph. 1999. L’architecture moderne en France. Tome II. Du chaos à la croissance. 1940-1966. Paris: Picard, 60.

Barjot, Dominique, Rémi Baudouï, and Danièle Voldman. eds. 1995. Op. cit., 335 sq.

Kuisel, Richard. 1981. Capitalism and the State in Modern France: Renovation and Economic Management in the Twentieth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 187.

Prothin, André. 1946. “Urbanisme et Reconstruction”. L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 7-8 (September): 2. The journal provides a comprehensive overview of the goals and initiatives associated with the reconstruction of the country, as well as with guidance on methods and legislative measures.

See in particular : Candré, Manuel, and Danièle Voldman. 1995. Une politique du logement. Ministère de la reconstruction et de l’urbanisme. 1944-1954. Paris: Plan construction et architecture. Institut français d’architecture. For more information on the creation of the MRU, see: Voldman, Danièle. 1997. Op. cit., 119 sq. and Voldman, Danièle. 1983. “Aux Origines Du Ministère de La Reconstruction”. In Les trois Reconstructions : 1919-1940-1945. Volume 3. 1940-1960. Industrialisation : reconstruction et exportation de la société française, edited by Jean-Pierre Épron, 1-4. Paris: Institut Français d’Architecture.

For regional or local studies on the second reconstruction in France, refer to the following sources: Vermandel, Frank. 1997. Le Nord de la France, laboratoire de la ville: trois reconstructions, Amiens, Dunkerque, Maubeuge. Lille: Espace Croisé; Jeanmonod, Thierry, Gilles Ragot, and Nicolas Nogue. 2003. L’invention d’une ville : Royan années 50. Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine; Bonin, Hubert, Sylvie Guillaume, and Bernard Lachaise. eds. 1997. Bordeaux et la Gironde pendant la Reconstruction, 1945-1954. Talence: Maison des sciences de l’homme; Plum, Gilles. 2011. L’architecture de La Reconstruction. Paris: Nicolas Chaudun; Vayssière, Bruno. 1998. Reconstruction. Déconstruction. Le « hard French » ou l’architecture française des Trente Glorieuses. Paris: Picard; Chélini, Michel-Pierre, and Roger Philippe. eds. 2017. Reconstruire le Nord-Pas-de-Calais après la Seconde Guerre mondiale (1944-1958). Villeneuve-d’Ascq: Presses Universitaires du Septentrion; Dieudonné, Patrick. 1994. Villes reconstruites: du dessin au destin. Volume I. Paris: L’Harmattan; Bouillot, Corinne. 2013. La reconstruction en Normandie et en Basse-Saxe après la Seconde guerre mondiale. Mont-Saint-Aignan: Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre; Auger, Jack, and Daniel Mornet. 1986. La Reconstruction de Caen. Rennes: Ouest-France; Bonillo, Jean-Lucien. 2008. La reconstruction à Marseille: architectures et projets urbains, 1940 – 1960. Marseille: Imbernon.

Guerrand, Roger-Henri. 1992. Op. cit., 174. These comfort features are described in greater detail in the following section: Ministère de la reconstruction et de l’urbanisme. 1945. Charte de l’architecte. Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 16-17.

Ministère de la reconstruction et de l’urbanisme. 1945. Charte de l’urbanisme. Paris: Imprimerie nationale.

Only his student record from the Ecole des Beaux-Arts de Paris exists. See his entry in: Crosnier Leconte, Marie-Laure. 2015. “Dictionnaire des élèves architectes de l’École des beaux-arts de Paris (1800-1968)”. https://agorha.inha.fr/ark:/54721/396feccb-32d5-4ecf-a605-4fd85428c974.

On the Chief Architect's missions, please see: Ministère de la reconstruction et de l’urbanisme. 1945. Charte de l’architecte. Op. cit., 10.

Grand Est et al. 2016. Op. cit., 13.

André, Jacques. 1946. “Saint-Dié, Plan d’aménagement”. L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 7–8 (September): 78.

Bauer, Caroline. 2022. Les frères André. L’architecture en héritage, architectures contemporaines. Paris: Hermann, 20 sq.

Jankowski drew up PRAs for several ruined rural communities: Anould, Corcieux, Gerbépal, Saint-Léonard and Saulcy-sur-Meurthe. See also his student file available in: Crosnier Leconte, Marie-Laure. 2015. “Dictionnaire des élèves architectes de l’École des beaux-arts de Paris (1800-1968)”. https://agorha.inha.fr/ark:/54721/fa0238ab-48b9-46c2-adc7-eefa3c572106.

Prost, Antoine. 2013. “Les monuments aux morts. Culte républicain ? Culte civique ? Culte patriotique ?”. In Les Lieux de mémoire. Tome I. La République, edited by Pierre Nora, 204. Paris: Gallimard.

Veschambre, Vincent. 2008. Op. cit., 10.

Voldman, Danièle. 1997. Op. cit., 151.

Abraham, Pol. 1946. Architecture préfabriquée. Paris: Dunod.

Jambard, Pierre. 2009. “La construction des grands ensembles, un échec des méthodes fordistes ? Le cas de la Société Auxiliaire d’Entreprises. 1950-1973”. Histoire, économie & société, no. 2: 138.

Delemontey, Yvan. 2015. Reconstruire la France. L’aventure du béton assemblé. 1940-1955. Paris: Éditions de la Villette, 101.

Ivi, 130 sq.

Monnier, Gérard. 2000. L’architecture du XXe siècle. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 75 sq.

Lyon-Caen, Jean-François, et al. 1983. “La Reconstruction dans les Alpes Françaises (1945-1955)”. In Les trois Reconstructions : 1919-1940-1945. Volume 3. 1940-1960. Industrialisation : Reconstruction et exportation de la société française, edited by Jean-Pierre Épron. Paris: Institut Français d’Architecture, 35.

Ivi, 35.

Sanyas, Hélène. 1983. “La profession d’architecte et le contrôle architectural durant la période de la reconstruction (1940-1945)”. In Les trois Reconstructions : 1919-1940-1945. Volume 3. 1940-1960. Industrialisation : Reconstruction et exportation de la société française, edited by Jean-Pierre Épron, 5-12. Paris: Institut Français d’Architecture.

Doyen, Mathilde, Toussaint, Aline, and Vanessa Varvenne. 2020. “L’architecture de la seconde reconstruction, un patrimoine pour le parc ?”. In Protéger, valoriser, intervenir sur l’architecture et l’urbanisme de la Seconde Reconstruction en France. Actualité et avenir d’un patrimoine méconnu, edited by Éléonore Buffler, Patrice Gourbin and Christel Palant-Frapier, 50. Gand : Snoeck.

Heinich, Nathalie. 2009. La fabrique du patrimoine. «De la cathédrale à la petite cuillère». Paris: Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 18.

Ivi, 21.

Linossier, Rachel, et al. 2004. “Effacer, conserver, transformer, valoriser : le renouvellement urbain face à la patrimonialisation”. Les Annales de la Recherche Urbaine, no. 1 (2004): 24.

Buffler, Éléonore, Gourbin, Patrice, and Christel Palant-Frapier. 2020. Op. cit., 20.

Bradel, Vincent. 1994. “Saint-Dié : sans Corbu ni maître”. In Villes reconstruites. Du dessin au destin. Tome 1, edited by Patrick Dieudonné, 293-304. Paris: L’Harmattan.

Henry, Jean-Yves. 2013. “La Seconde Reconstruction Dans l’est Des Vosges”.Situ, no. 21 (July).

Grand Est et al. 2016. Op. cit.

Audi, Robert. 2014. “Normativity and Generality in Ethics and Aesthetics”. The Journal of Ethics, no. 4 (December): 375. Original emphasis.

Beardsley, Monroe C. 1958. Aesthetics: Problems in the Philosophy of Criticism. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 457.

Berger, Jade, et al. 2021. “Débattre la Reconstruction. Le rôle des avant-projets et documents rectificatifs dans l’attribution de la valeur patrimoniale d’un édifice“. In Les fonds iconographiques et audiovisuels de la Reconstruction de 1940 aux années 1960.

Heinich, Nathalie. 2009. Op. cit., 231.

Note from the author: Leniau, Jean-Michel. 1992. L’utopie française, essai sur le patrimoine, Paris: Mengès.

Veschambre, Vincent. 2008. Op. cit., 49.

Graf, Franz. 2014. Histoire matérielle du bâti et projet de sauvegarde: devenir de l’architecture moderne et contemporaine. Lausanne: Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes, 11.

Abensour, Alexandre. 2014. La mémoire, textes choisis. Paris: Flammarion, 203.

Halbwachs, Maurice. 1925. Les cadres sociaux de la mémoire. Paris: Alcan, 206.

Ibid.

Ricoeur, Paul. 2000. La mémoire, l’histoire, l’oubli. Paris: Seuil, 648.

Baudouï, Rémi. 1997. “Imaginaires culturels et représentations des processus de reconstruction en Europe après 1945“. In Les Reconstructions en Europe (1945-1949) edited by Dominique Barjot, Rémi Baudouï et Danièle Voldman, 310. Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe.

For a perspective on 20th-century architectural heritage as a material and cultural resource, refer to: Grandvoinnet, Philippe. 2022. L’architecture du XXe siècle: patrimoine culturel et matière à projet. Paris: Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des monuments nationaux.

Tom Avermaete Leonardo Zuccaro Marchi

Lisa Henicz

Giulia Bellato

Edited by: Elisa Boeri, Elena Fioretto and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)