In the choruses from The Rock (1934), T.S. Eliot speculates on what the future holds for the Church, summed up in the rejection and abandonment of sacred buildings. To the ethical decadence of the world, the poet opposes a new spirituality, capable of redeeming the city in the conviction that “the Church must be forever building, and always decaying, and always being restored”. This symbolic rebirth of the church building became crucial in the aftermath of WWII, prompted by the debate on what to do with ruined churches, many of which had been damaged during the recent German air raids. Various personalities, such as the historian Nikolaus Pevsner and the architect Henri Stuart Goodhart-Rendel, expressed themselves on the subject through newspapers, books and radio broadcasts. Among the options, the preservation of churches’ remains and their eventual transformation into war memorials, as proposed in the volume Bombed Churches as War Memorials (1945), harked back to that ‘pleasure of ruins’ so much celebrated by the English Romantic tradition and, more recently (1953) by the writer Rose Macaulay. On the other hand, the reconstruction of churches implied different approaches to restoration. While some famous churches were rebuilt in a philological manner, economic and technological reasons often encouraged reconstructions in simplified forms that only vaguely evoked ancient ones. In some cases, ancient fragments or rubble from the sacred ruins were integrated into the new structure as relics, testifying to the spiritual value attributed to the church’s martyred body. Reconstructions also impacted the building’s functionality. In many cases, a major liturgical reordering was carried out, improving the adherence of sacred space to modern liturgical principles. Meanwhile, the increasing secularisation of the 1960s gave rise to the phenomenon of redundant churches. Some of them were left in ruin and threatened with demolition, stimulating the establishment (1969) of the Redundant Churches Fund. Others were restored and converted to new secular use. Through the analysis of some case studies, the contribution investigates the monumentalisation and reuse of ruined churches in post-war Britain. The phenomenon was related to theories of restoration, social and urban planning policies, liturgical needs, and the sensitivity of designers called upon to respond to the complexity and contingency of the subject.

There are many architectural testimonies left by buildings damaged or destroyed by wars, just as there are many ways in which they can be repaired1. In addition to restoration à l’identique, i.e. the recovering of the ‘original’ facies, one can proceed with a new design substituting the old building, a re-functionalization of the remains, a reintegration of the ruins into the landscape, a recomposition into a new structure, and so on. The choice is conditioned by multiple and varied evaluations: economic, cultural, symbolic, technical. Ultimately: political. Above all the reasons and choices hovers the reminder of the intangible value of memory, understood as a collective feeling and as the identity glue of a community, which buildings have materially represented in order to hand it down from generation to generation2. John Ruskin, in order to emphasize how, in architecture, memory is combined with the living testimony of man’s manual ability, acting in a specific cultural and social context, wrote:

Let us think, as we lay stone on stone, that a time is to come when those stones will be held sacred because our hands have touched them3.

The memory of men, of which the stones are repositories, sums up both the spirit of those who shaped the material – the shared sentiment of a community that wanted the building – and the response to a moral imperative of transmitting immaterial values through a concrete artefact.

These conditions are particularly and traditionally suited to religious architecture. Indeed, it is the choral product of architects, engineers, artists, craftsmen, and simple workers, whom Romantic culture was pleased to imagine united and driven by a common spiritual feeling. Their hands ennoble matter, transforming it from brute matter to signified matter. In sacred architecture, the metaphysical purpose of human effort establishes a stringent link between the immanent and transcendent dimensions of construction. At this juncture, the symbolic charge of the building infuses a special character, of intrinsic sacredness, to the very material of construction. Consequently, in agreement with Ruskin, the use of an ecclesiastical building, and even its remains, is inevitably conditioned by the original consecration, whose spirit is preserved and transmitted to future generations.

It is not useless to recall that in English culture, the mnemonic process stimulated by the vestiges of ruined architecture is charged with aesthetic meanings and moral exhortations that descend from the Romantic concepts of the sublime and the picturesque. The literary topos of the sublime, unleashed by ruins and their capacity to evoke imaginary reconstructions, have persisted until contemporary times. In particular, it influenced several projects for the reconstruction of sacred architecture mutilated by the Second World War.

Still in the first half of the 20th century, the fascination with the allure of ruins was driven by an enduring wave of writers and artists, who were engrossed in what can be described as a resurgence of “modern romanticism4”. This artistic and literary movement breathed new life into the exploration of decayed and dilapidated landscapes, inviting artists to delve into the profound emotions evoked by these remnants of the past. In their vision, the crumbling architecture served as a mirror through which society could confront its own transience and reflect on cyclical patterns of growth and decline. A similar interpretation was provided by the Anglo-Catholic writer Thomas Stearn Eliot. In 1934 he composed The Rock, a play cenetred on the construction of a new church building by a group of men from London. In the choruses, the author engaged in contemplation regarding the forthcoming trajectory of the Church. This was encapsulated in the rejection and abandonment of sacred edifices. In response to the moral decline prevalent in the world, the poet posited a novel form of spirituality, one endowed with the potential to redeem the urban landscape. This conviction held that ‘the Church must be forever building, and always decaying, and always being restored5’. Eliot saw the Church as the emblem of an enduring cycle of construction, decline, and renovation.

The allegorical revival of church structures praised by Eliot assumed a pivotal role in post-World War II Britain, particularly in the context of the deliberations concerning the fate of ruined churches. Many ecclesiastical sites had suffered damage during the recent air raids by German forces, thereby prompting a profound discourse on their future.

During the Second World War, Britain had been hit by some of the heaviest bombings, resulting in a large number of ruins. This spurred a renewed and extensive discussion on the reconstruction of cities, as noted by scholars6. This discourse dates back to the 1943 exhibition on ‘Rebuilding Britain,’ which was organized at the National Gallery by the Royal Institute of British Architects7. While the post-war destruction promoted a new approach to land planning, the extensive presence of ruins also revived romantic sentiments8. The theoretical basis of Anglo-Saxon post-war ruinism was founded on a number of writings, including The Bombed Buildings of Britain, edited by historian James Maude Richards with notes by John Summerson9. It was written with the dual function of an obituary and a pictorial register of the buildings destroyed by Nazi air raids10. To appreciate the pictorial aspect, the reader was asked to consider the rubble as ruins, that is, as an architectural event in its own right11. Although, the authors warned, what remains of the destroyed buildings represents a loss of life and material goods, the persistent symbolic value justifies the admiration reserved for their contingent state. An analogous reading was made in Pleasure of Ruins (1953, fig. 1), in whose pages Rose Macaulay extended the 19th-century Romantic tradition to the rubble of the Second World War:

The bombed churches and cathedrals of Europe give use, on the whole, nothing but resentful sadness, like the bombed cities [...] Caen, Rouen, Coventry, the City churches, the German and Belgian cathedrals, brooded in stark gauntness redeemed only a little by pride: one reflects that with just such pangs of anger and loss people in other centuries looked on those ruins newly made which to-day have mellowed into ruins plus beau que la beauté12.

Although not primary military targets, many churches had been destroyed during the Nazi raids. In those cases, the contemplation of ruin did not always prevail over the demand for the rebirth of bombed-out churches. In post-war England, ravaged by five years of Nazi bombing, the future of ruined churches was a hot topic of debate, in which designers, historians, and architectural critics take part. Prominent among them were the names of the legendary Nikolaus Pevsner and the architect Henri Stuart Goodhart-Rendel, nodal references in the field of sacred architecture, who were interviewed in two BBC radio shows immediately after the destruction13.

In Goodhart-Rendel’s interview, recorded in the aftermath of the 1941 bombing, the testimonial value of the wounds of architecture emerged. It was proudly displayed on the body of the building like the scars on the bodies of warriors:

I hope our British cities will be proud of their scars, as heaven knows they have the right to be, and will not putty up all the shrapnel holes and mend all the broken stones without need. Where these defects spoil good architecture they should of course be effaced, but in many buildings the architecture will not seem to posterity nearly so important as the scars14.

Goodhart-Rendel’s reflection on the cautionary and celebratory significance of the scar, contrary to ruinist thinking, was however conditioned by the primary interest of the integrity of the building15. Pragmatically pursuing the goal of reuse, the architect proposed three paths to take in the case of bombed-out churches: repair, reproduce, replace. Repair was seen as a must for damaged churches; but if the extent of destruction was huge, they were not to be rebuilt exactly as they were. This would be a double mistake, firstly because of the outdatedness of the old space compared to modern worship needs, and secondly because of the historically questionable artificiality of reconstruction. Only when some original fragments survive, Goodhart-Rendel admitted the possibility of replicating the original design, although it was preferable to “embody the ancient work in a new design [...] letting the building look what it is, a mixture of old and new16”. The churches rebuilt by Goodhart-Rendel still looked as Victorian architecture, in the name of a stylistic continuity that made it difficult to distinguish between the pre-existing and the new intervention. Instead, the variety of approaches envisaged by his words emerged in the daily practice of other British designers, called upon to apply restoration principles according to the contingencies of the case17. Among those most active in post-war sacred architecture was the couple John Seely and Paul Paget, who reconstructed the interior of St Andrew’s Church in Holborn in a manner philologically faithful to the original18. They also authored more liberal reconstructions, exemplified by the work for St Mary’s Church in Hammersmith, London. Erected on the site of a 19th-century chapel totally destroyed by Nazi bombing except for the crypt, the new church exhibited modern forms and materials, although hybridized by citations of traditional architecture: from the lunetted aedicule on the façade to the sequence of polylobate concrete beams, which recalled the hammer-beam roof of English Gothic (figg. 2a and 2b).

The freedom to differentiate reconstructions from their original designs offered a multi-faceted array of benefits, particularly from an economic, technical, and distributional point of view. In cases where the integrity of the building envelope needed to be conserved, a common approach emerged: incorporating a self-sustaining internal structure that capitalizes on contemporary construction methods. Simultaneously, the restoration of churches swiftly evolved into a chance to modernize the liturgical area, modifying its proportions to align with the community’s evolving requirements and adjusting the emphasis on various liturgical focal points. Primarily, when circumstances allowed, reconstruction opened doors to the reimagining of church spaces as a cohesive entity, enhancing the feeling of affiliation among the entire worshiping congregation.

The necessity to undertake reconstruction using contemporary materials and in alignment with modern liturgical principles was central to the report presented by Bristol architect Thomas H. Burrough at a conference in Attingham Park, Shrewsbury, in 196119. In the reconstructions of church interiors, labeled as radical reordering by Burrough, new materials like steel and reinforced concrete maximized open space without additional supports. The new layout enhanced altar visibility and symbolically represented the unified congregation participating in the liturgy20. Burrough implemented this approach in various reconstructions within the Bristol diocese. Notably, in the case of the Holy Trinity Church in Hotwells (1959), only the neoclassical façade and perimeter walls were retained21. The former walls surrounded an open layout marked by slender vertical seams of rolled steel, encased in wooden boxes adorned with black and gold. Likewise, in 1957, Burrough reconstructed St. Andrew’s Church in Avonmouth (fig. 3), using reinforced concrete pillars to divide the nave from the remodeled aisle, “rebuilt more like a second aisle to increase the effect of space22”.

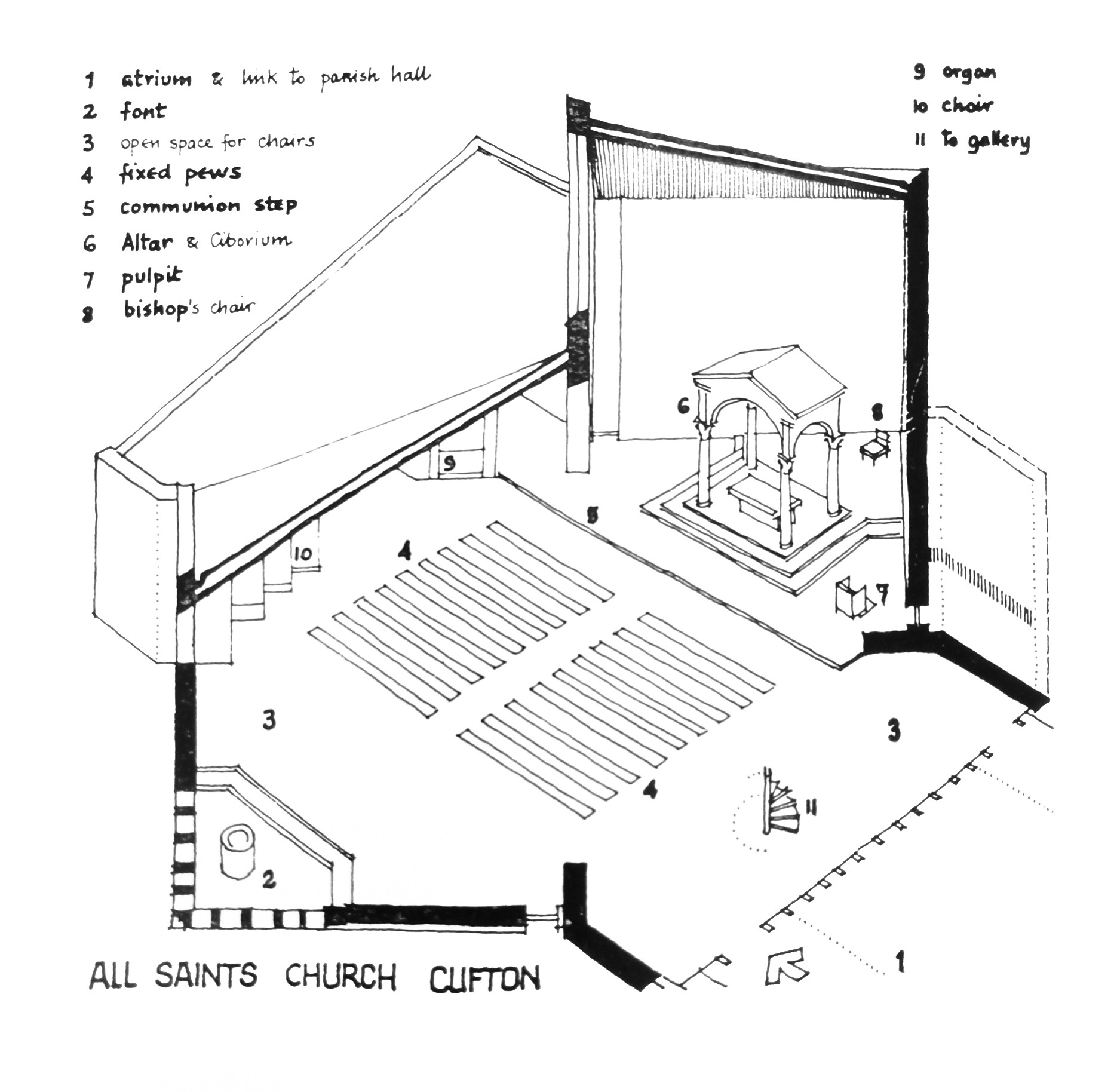

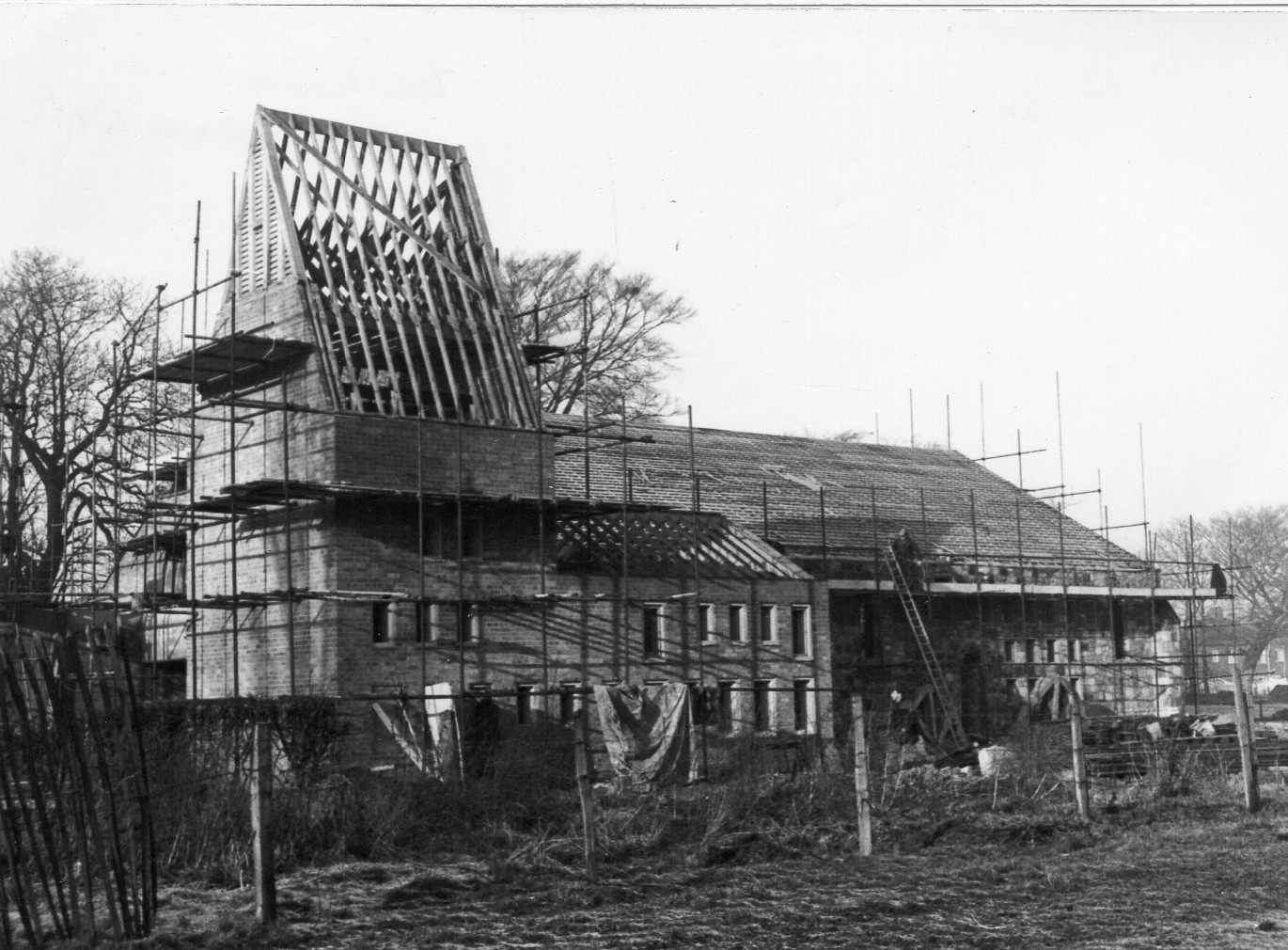

In the Bristol diocese, an alternate approach was embraced for the neo-Gothic All Saints Church in Clifton. Designed between 1868 and 1872 by the renowned architect George Edmund Street and subsequently modified by George Frederick Bodley and F. C. Eden, the church had witnessed the early Anglo-Catholic endeavors in liturgy, influenced by continental styles. Ravaged during the bombing raids of 1940, minor harm befell solely a portion of the bell tower, sacristy, and narthex23. Renowned church architect William Randall Blacking was entrusted with the task of reconstructing the church. His project aimed to conserve the outer walls of the structure while adapting the plan according to the surviving remnants. Unfortunately, upon Blacking’s passing in 1958, only a provisional church, featuring a canopy that still drapes over the high altar, had been realized. The responsibility then shifted to Robert Potter, a pupil of Randall Blacking, who encountered insurmountable challenges in maintaining the existing walls. Consequently, he dismantled the perimeter walls, retaining solely the belfry and narthex from the original edifice24. These elements were linked with a contemporary structure, consecrated in 1967 (fig. 4).

Between the narthex and the sacristy, a novel rectangular structure featuring opposing triangular apses was introduced. This addition prompted a 90-degree rotation of the interior layout, departing from that of the former nave. The reconstruction eloquently demonstrated a cognizance of modern liturgical concepts. Positioned in alignment with traditional eastward orientation, the new high altar took its place to the east, while on the western side, the baptistery emerged, enveloped by tall stained-glass windows crafted by John Piper. Unobstructed by columns, the expansive unified space offered clear sightlines, extending even to the upper gallery, where the women’s chapel was situated. This elevated section was ingeniously cantilevered, resting on the perimeter walls, with its sole central support being a spiral staircase.

The importance of music was visually underscored by the strategic placement of the organ close to the altar and congregation, as if its harmonies were harmoniously interwoven with the voices of the faithful. Adjacent to it, an original Gothic archway – the entrance of the former Street’s church – led to a porch dating back to 1909, which was thoughtfully transformed into the Chapel of St. Richard of Chichester. This chapel stood as a tribute to the church’s founders25.

The connection between the former church and the modern construction was even more apparent externally. The new structure, resembling a crystalline form with its faceted design and vertical bands of glass, dynamically echoed the vertical essence of the Gothic aesthetic. Atop the masonry tower, a tall spire crafted from laminated wood and adorned in aluminum provided the crowning touch. The distinct geometric forms and varied hues of the new design served to accentuate the contrast with the remaining remnants of the Victorian church, standing as lasting reminders of the devastation.

Beyond their role as vessels of historical recollection, ruins embodied the deep-rooted core of ritualistic sanctity. This notion mirrored the theological principle underpinning relics, where material substance carried the ability to convey the sacred through contact, fostering an alluring interplay between the tangible and the spiritual. Similar to relics, the vestiges of churches also necessitated presentation and display26. In instances where ruins emerged due to wartime devastation, the fundamental concept lied in the belief that the material of the religious building gained added sanctity through the martyrdom endured by the building. Therefore, incorporating the rubble into a newly built church renewed its sacredness ab origine. Certainly, the repurposing of debris as construction material for religious architecture became a common practice in post-World War II Europe. This act symbolically embodied the parable of Christ as the living stone (1 Peter 2:4-5). Examples span from the walls “made from the stones of a ruin” in Le Corbusier’s chapel at Ronchamp (1951), which reused the “rubble stone” of the previously bombed chapel27, to the incorporation of ancient stone by Rudolf Schwarz in the new building of St. Anna in Duren (1956)28.

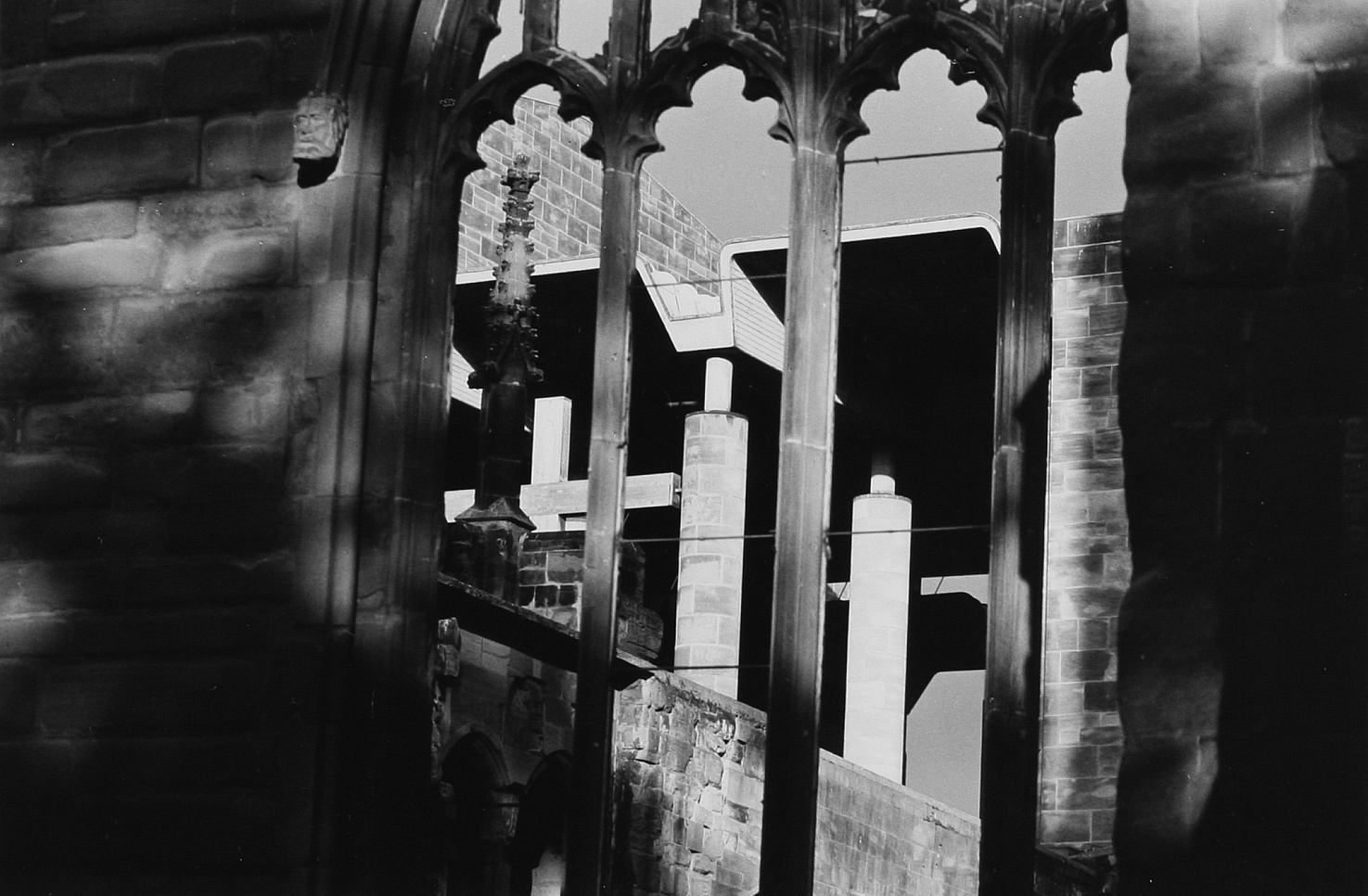

In the context of British architecture, Stephen Dykes Bower led the reconstruction of St. John the Evangelist in Newbury (1955–57), incorporating glass and brick salvaged from the earlier Victorian church designed by William Butterfield29. Singularly, George Pace, who also participated in the 1961 conference at Attingham Park, adopted a unique approach by repurposing entire sections of a ruined church in York to construct a new building30. The old St. Mary Bishophill Senior in York, which had been abandoned since 1930 and was eventually demolished in 1963, was partially re-erected within the new church of the Holy Redeemer (1962-64)31. Pace not only preserved historical traces of the demolished church as relics but also incorporated them as characterizing elements into the layout of the new space. The pointed arches of the old church defined the new southern aisles, while the concrete frames of the southern wall found their spaces adorned with timeworn stones. A substantial ancient portal stood as the demarcation between the vestibule and the nave. The lectern and the altar stone of the Lady Chapel reused materials from the same site (figg. 5a and 5b).

In different scenarios, even if not employed directly as salvaged materials, ruins forged intangible connections with the site’s memories, amplifying the symbolic significance of the new buildings erected on the site. This premise was accompanied by a set of methods that the architects implemented to augment the sanctity of ancient remnants. For instance, in the project for the chapel of the Madonna in den Trümmern (Our Lady in the Rubble) erected in Cologne (1947), Gottfried Böhm attached a new small octagonal sanctuary to the remains of the Romanesque church of St. Kolumba32. Stones, decorative fragments, the stumps of pillars, and sections of the original church floor were intentionally placed around the contemporary perforated structure. This arrangement established a tangible and symbolic link between the ongoing celebration within the chapel and the unfolding garden of ruins outside, connecting them materially and visually33. Böhm’s intervention had a worldwide echo. In Britain, a notable instance revolved around Coventry Cathedral. Situated in the heart of the Midlands, the city suffered devastating bombings during the Coventry Blitz on 14 November 1940, leading to the destruction of St. Michael’s Cathedral in a blaze. The lingering remnants were captured in the aftermath of the attack by several artists, but the most touching images were those painted by John Piper. While falling within a particular artistic tradition, characterized by its textured impasto and vibrant hues, Piper’s portrayals of the bombed Coventry Cathedral surpassed mere contemplation of life’s transience. They depicted the tangible essence of the ruins as a corporeal presence:

The walls have fallen, but in Piper’s paintings there is an insistence on substantiality. Stones, bricks, mortar plead against transience34.

The cathedral’s deteriorating walls assumed an iconographic significance, akin to the wounded bodies of martyrs, laid bare for believers to attest to their historical existence. The remnants attained such a profound symbolic status that they provided a striking setting for the installation of the new bishop, Neville Gorton. This event occurred on 20 February 1943 amidst the cathedral's ruins (fig. 6), within a symbolic milieu that ignited the city’s imagination, akin to the Phoenix ascending from its ashes that was added to the city’s coat of arms35.

The remnants of the church served as a precursor to its reconstruction, ranking among the initial focal points of Gorton’s time as bishop. In fact, in 1942, Gorton enlisted architect Giles Gilbert Scott to formulate a design. Scott’s blueprint aimed to conserve the vestiges of the Gothic structure, seamlessly fusing them into the neo-Gothic architectural style. However, this amalgamation of styles inadvertently diminished the distinctiveness of the ruins, subsequently obscuring their symbolic essence. The project encountered opposition from numerous critics, including James Maude Richards and Nikolaus Pevsner, to the extent that Gilbert Scott tendered his resignation in 194636. A few years later, in 1951, a competition was organized to select a design for a new cathedral.

The brief for the new cathedral only required the tower and the two medieval crypts to be kept, while giving freedom to the designer to integrate or demolish the remaining parts. The several proposals elaborated the relationships with ruins differently37. For instance, Alison and Peter Smithson’s entry, showed at the “20th century form: Painting, sculpture and architecture” exhibition (1953) at the Whitechapel Art Gallery and enthusiastically described in the pages of Liturgy and Architecture (1960) by Peter Hammond38, preserved only the old apse, isolated as a holy relic, alongside the crypts and the tower. Simultaneously, the architects separated the new church from the old one by employing a distinct materiality and elevated it from the ‘archeological’ level through the use of pillars. In another entry, Colin St. John Wilson, who would become famous above all for the project of the British Library (1973-1997, with Mary Jane Long), and Peter Carter proposed a spaceframe canopy39. It formed a transparent glass box that established direct visual contact between the rituals inside and the ruins outside, which were limited to the apse and tower and isolated from the new building. The project, which aimed to blend religious symbolism and advanced technology in a novel form that Wilson termed ‘mechanolatry’, was featured in the Architects’ Journal, receiving approval from architects and critics such as Reyner Banham40. However, these projects were deemed by the jury to clash with their extreme modernity, and furthermore, they only preserved a small portion of the overall ruins. For these reasons, they did not win the competition.

When comparing the competition for Coventry’s cathedral with those for the rebuilding of churches in other countries, it’s interesting to note that a few years later, a similar debate surrounded the competition (1957) for the reconstruction of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial Church in Berlin41.

In this case, only a section of the old German church, damaged during the bombing, was retained. As in the projects for Coventry of Alison and Peter Smithson or Colin St. John Wilson and Peter Carter, the remnants of the Berlin church were kept isolated and distinguished in terms of language, proportions, and materials from the new modern structure erected (1959-1963) by Egon Eiermann.

Coming back to Coventry, the winning proposal by Basil Spence, reached a compromise. It conserved a much larger section of the old cathedral and recalled its size and its atmosphere through a neo-Gothic church constructed with modern techniques. Although it was harshly criticized by critics for its old liturgical conception and architectural language, the project signified a fresh trajectory for the reconstruction of churches ravaged by bombing. Spence conceived the idea of erecting a contemporary cathedral using stone and reinforced concrete, situated alongside the boundaries of the former structure, which was retained in nearly all its fragmented state:

As soon as I set foot on the ruined nave I felt the impact of delicate enclosure. It was still a cathedral. Instead of the beautiful wooden roof it had the skies as a vault. This was a Holy Place, and although the Conditions specified that we need to keep only the tower, spire, and the two crypt chapels, I felt I could not destroy this beautiful place, and that whatever else I did, I would preserve as much of the old Cathedral as I could42.

The outline of the medieval structure then defined the boundaries of a garden of remembrance, eternally carrying the scars of conflict. The fragments left behind by the cathedral, ravaged by bombings, stood in stark juxtaposition to the vitality of the revived contemporary edifice, which rose prominently beside the time-honored Gothic windows. This architectural interplay was eloquently articulated by Spence:

I saw the old Cathedral as standing clearly for the Sacrifice, one side of the Christian faith, and I knew my task was to design a new one which should stand for the Triumph of the Resurrection43.

The remains of the demolished church acquired an equivalent theological importance and liturgical purpose as the newly restored church (fig. 7).

The liturgical impact became apparent through the ceremonies held within the confines of the former cathedral, as well as in the repurposing of its materials. Notably, this was exemplified by three nails salvaged from the ruined medieval roof, integrated into a cross fashioned by sculptor Geoffrey Clarke for the new high altar, imbuing them with a contemporary relic-like significance.

Despite the obsolescence of its liturgical conception, not updated to the liturgical innovations experimented in those years, the cathedral’s long, majestic interior had a positive impact on the public, quickly becoming the major attraction of the city. Moreover, it was used as a space for lay representation, hosting events such as ballets and concerts, in line with the widespread practice of secular use of church buildings promoted in those years44.

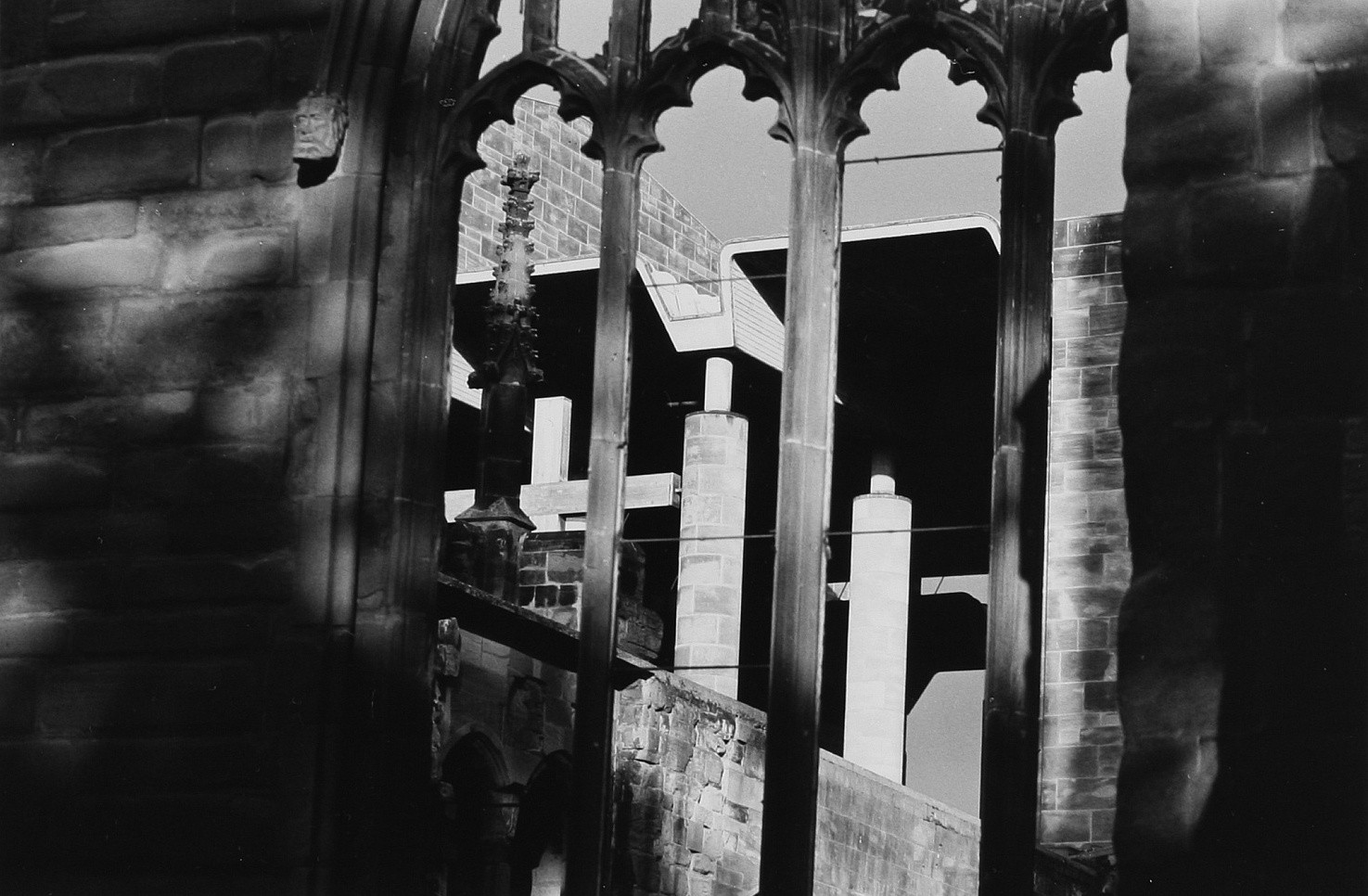

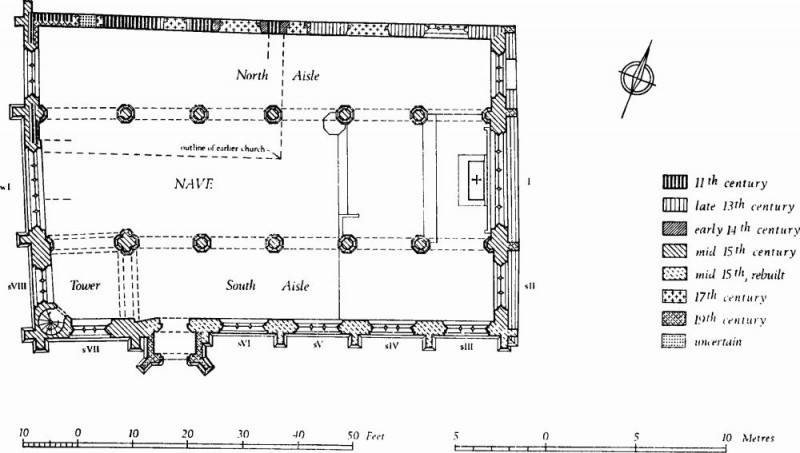

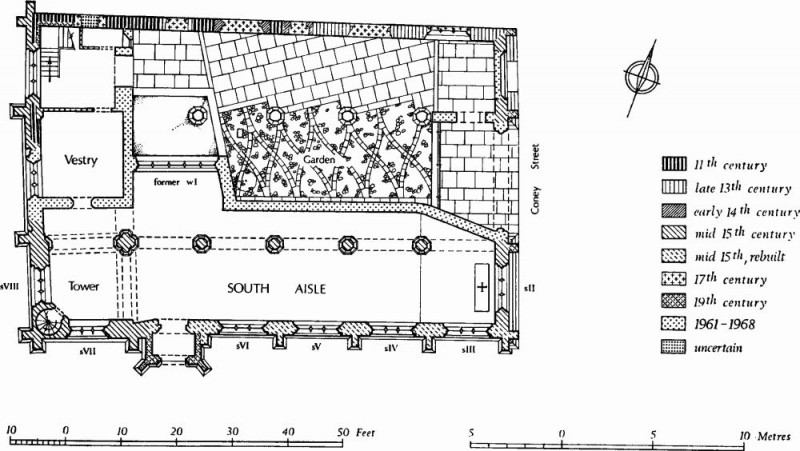

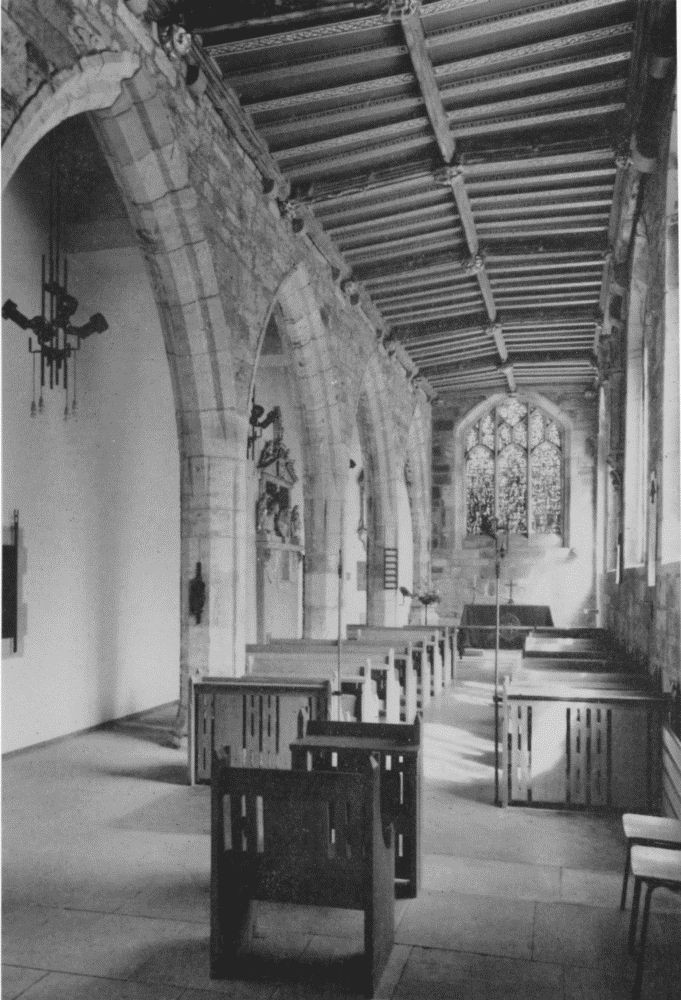

Through the blueprint of the new Coventry Cathedral, the devastated church was transformed into a Sanctuary of Remembrance (figg. 8a and 8b). This designation infused the location with sanctity derived not solely from its religious role but also from the recollections of the incidents it bore witness to. This very objective was equally pursued in the restoration of St. Martin Le Grand Church in York, which had suffered destruction due to bombing in 1942 (figg. 8c and 8d)45.

Between 1961 and 1968, architect George Pace oversaw the restoration of the liturgical hall, revitalizing only a segment of the original layout. This newly defined space, slightly more expansive than the south aisle, was conceived as “a shrine of remembrance for all who died in the two world wars, a chapel of peace and reconciliation between nations and between men46”. With the exception of the vestibule and a small office nestled in the north-west corner, the remaining expanse encompassing the nave and north aisle was intentionally left open. This space underwent a transformation into a hortus conclusus, reminiscent of Gethsemane. Within this garden of memories crafted from stone, the remnants of four pillars from the ancient nave, while bearing the scars of wartime destruction, evoked the imagery of the fractured column associated with the Passion of Christ. Augmenting the contemplative role of the area, a commemorative cross and a bench were positioned, underscoring its sacred nature. Enhancing its sanctity were a water pool and a deciduous tree. This same principle of distinct structures was applied by Pace in his restoration of All Saints’ Church in Pontefract47 (Pace 1990, 138-139). The aged ruins underwent rejuvenation through the incorporation of a novel structure, finalized in 1967, inserted within the confines of the former nave walls48.

Initially intended for different functions, the area within the borders of ruined churches, once officiated, persisted as a space of reverence. It continued to serve as a locus for devotion and religious practices. This concept should be understood by delving into the Latin root of ‘cultus’, which encompassed both the notions of worship and cultivation. The connection is not happenstance: within churches ravaged by the Second World War, left as mere ruins, the remembrance of those who perished in the conflict flourished intangibly, paralleled by the growth of physical vegetation. In this context, as expressed by Marc Augé in his acclaimed essay on ruins and wreckage, these earthly vestiges of buildings guided people us in the craft of perceiving time, facilitating a richer understanding of history to flourish:

While everything contributes to making us believe that history is over and that the world is a spectacle in which that end is represented, we need to rediscover time in order to believe in history. This could be the pedagogical vocation of ruins today49.

A multitude of churches that had been devastated were indeed converted into commemorative gardens, a strategy that was already under consideration in the United Kingdom after the war’s conclusion50. This concept was exemplified by the significant volume on Bombed Churches as War Memorials (1945), that expanded on a suggestion first put forward by The Architectural Review.

The magazine had published an editorial advocating for the preservation of city ruins51. The discourse was taken up again in a letter to The Times by a group of intellectuals52.

They were: landscape architect Marjory Allen, historian David Cecil, art historian Kenneth Clark, Anglican canon Frederic Arthur Cockin, writer Thomas Stearns Eliot, architect Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel, biologist and writer Julian Huxley, Keynes, and ecologist Edward James Salisbury. The letter, dated August 15, 1944, insisted that the war memorials erected after the war were unworthy of the sacrifice they commemorated and that a new kind of memorial was needed. Therefore, they proposed to use ruins for this purpose, with minimal work done to preserve them from further decay, reorganizing them as gardens. Ruined churches, in particular, could also be used for open-air services and were mainly intended as instruments against collective forgetting:

The time will come –much sooner than most of us to-day can visualize– when no trace of death from the air will be left in the streets of rebuilt London. At such a time the story of the blitz may begin to seem unreal not only to visiting tourists but to a new generation of Londoners. It is the purpose of war memorial to remind posterity of the reality of the sacrifices upon which its apparent security has been built. These church ruins, we suggest, would do this with realism and gravity53.

The letter was re-published in The Architectural Review, as well as in Bombed Churches as War Memorials. The book summarized the debate, and expounded it with inputs from architects Hugh Casson, Brenda Colvin, and Jacques Groag. The volume opened with a foreword by the Dean of St. Paul Walter R. Matthews, who warned against an excessive pragmatism that could compromise the intangible and spiritual value of beauty:

The devastation of war has given us an opportunity which will never come again. If we do not make a City of London worthy of the spirit of those who fought the Battle of Britain and the Battle of London, posterity will rise and curse us for unimaginative fools54.

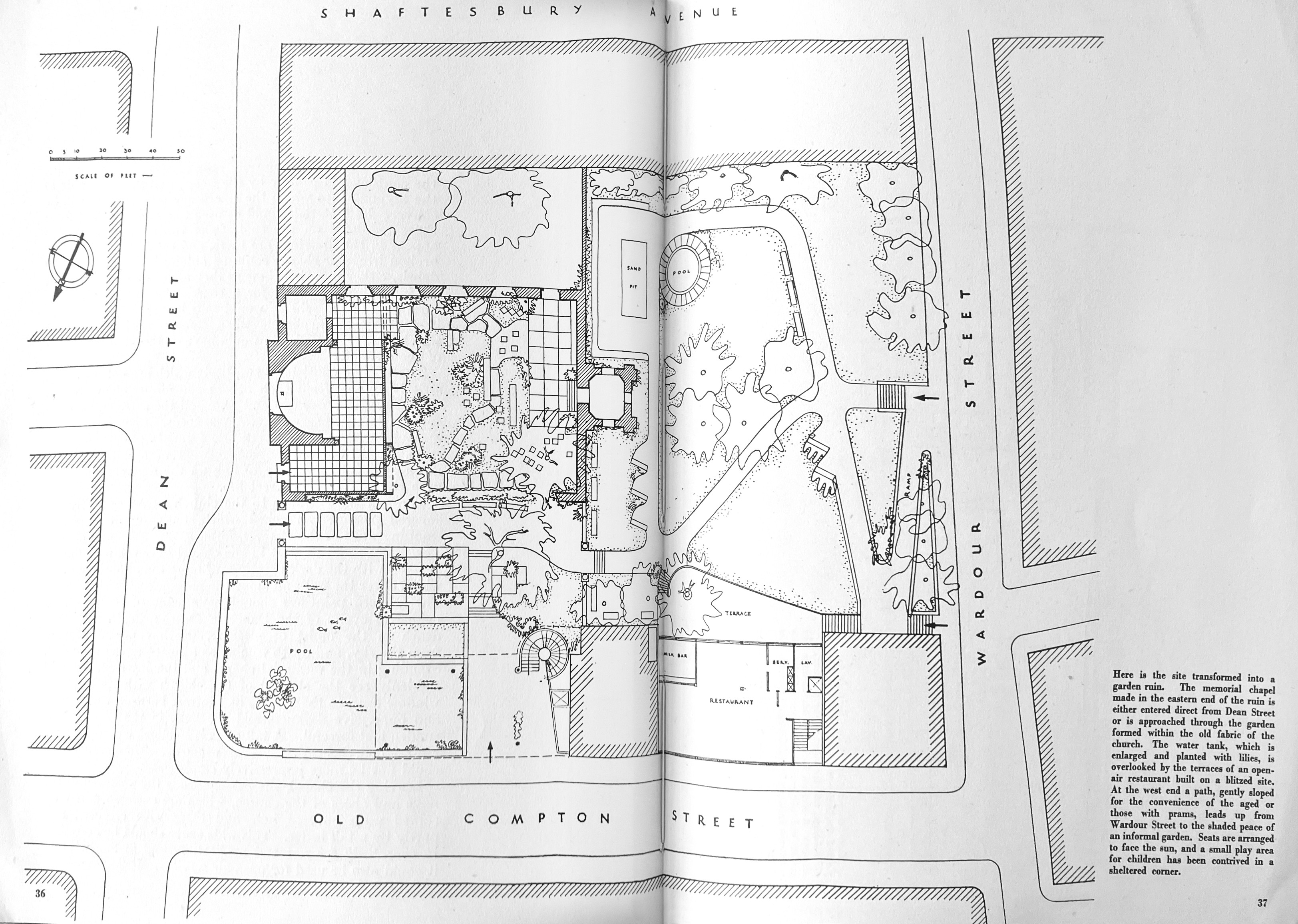

In the following pages, authors advocated for turning of ruins into monumental forms, proposing specific transformation projects (fig. 9)55.

The proposition found practical implementation in several instances. One such case was the Gothic St. Peter’s Church in Bristol, constructed on the grounds of the city’s inaugural church. It was intentionally preserved in its ruined state, standing as a testament to the toll of war. A similar trajectory unfolded for St. Dunstan in the East Church in London—a venerable medieval edifice previously reconstructed after the Great Fire of 1666, featuring a bell tower by Christopher Wren, with its nave revamped in 1817-21 by David Laing. Ravaged by the Blitz in 1941, only fragments of the tower and certain walls endured. Consequently, in 1967, the City of London Corporation chose to transform its remnants into a public garden space. This narrative resonated with the fate of Christ Church Greyfriars, situated not far away in London. Originally reconstructed (1687) by Wren following the fire, it suffered fire damage in 1940, leaving behind only the tower and stone walls. Following the ongoing debate, in 1949 the decision was made to leave the church in ruins56.

In ruined churches, the completeness of the architectural structure was inconsequential, even if elements like the roof or substantial sections were absent. It was the enclosure itself that defined the space and established its initial purpose: the area within it was consecrated and set apart from the ordinary ground. The significance of this spatial delineation was evident in actions such as the restoration of St. Mary Aldermanbury Church, one of Christopher Wren’s designs in the City of London. After extensive debates regarding whether to preserve or demolish its ruins, driven by the potential economic use of the property, the remnants of the edifice were relocated to the Westminster College campus in Fulton, Missouri. There, the church was reconstructed as a tribute to Winston Churchill. In contrast, the original location was transformed into a garden, inaugurated in 1970, which maintains the outline of the old church’s footprint on the ground57. In this instance, the architectural imprint acted as a form of metonymy, or that rhetorical device where a part signifies the entirety. It represented an intangible and spiritual fragment that resided within the communal consciousness, infusing the physical remnants of the structure with added sanctity.

While facing occasional allegations of sacrilege, the incorporation of secular activities that engaged the faithful beyond regular service hours played a pivotal role in rejuvenating numerous religious communities. In fact, churches had been grappling with the rising tide of secularization, resulting in dwindling attendance rates, particularly pronounced among Anglicans, which left many places of worship virtually deserted. Consequently, several parishes found themselves unable to cover the upkeep expenses of expansive historical structures. As a result, a considerable number of historic churches were labeled as ‘redundant’, and a portion of these left to languish, were intentionally left to decay, often with the removal of roofs, windows, and doors. An illustrative case was St. Peter’s in Edlington, South Yorkshire, which later found rescue and repurpose for civic use, while many others faced the imminent threat of demolition. Against this problematic background, in 1957, Welsh journalist and Conservative MP Ivor Bulmer-Thomas formed ‘The Friends of Friendless Churches. The founding group also included the aforementioned Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel, John Piper, John Summerson, and Thomas Stern Eliot, as well as figures such as politicians Roy Harris Jenkins, Rosalie Glynn Grylls and John Lindsay Eric Smith, or poet John Betjeman58. The main goal of the association was to “save disused but beautiful old places of worship of architectural and historical interest from demolition, decay and unsympathetic conversion59”.

The society actively advocated for the safeguarding of churches and their transformation into appropriate functions. In this regard, certain functions were deemed compatible with the character of church buildings, while others were seen as potentially compromising the essence of the structure. Activities related to governance, administration, and culture were generally perceived as more harmonious with the building’s nature, whereas commercial and leisure-oriented activities were often regarded as insufficiently reverent towards the building’s inherent spirit.

An emphatic resistance, for instance, thwarted the conversion of St. Mark Church in Clerkenwell, London. Erected between 1825 and 1827 in the Gothic style, the church was conceived under the guidance of William Chadwell Mylne. During the Blitz in 1941, the structure endured damage, including partial destruction of the roof. Architect H. Norman Haines, who would later design Christ Church in Cardiff (1963), spearheaded the restoration efforts, successfully concluding them in 1962. The roof was meticulously reconstructed using a steel framework, bolstered by six newly added slender concrete columns (figg. 10a and 10b).

In 1968, the task was assigned to Basil Spence to diminish the church’s footprint to accommodate new areas for a school. These encompassed a capacious assembly hall, cafeteria, music and gymnasium spaces, a kitchen, restrooms, and service facilities on the first level. Additionally, classrooms were envisaged on the two upper floors, seamlessly integrated within the height of the nave. The bell tower was intended to house tranquil rooms for reading and relaxation. Nevertheless, the proposal faced an obstacle as planning permission was ultimately declined60.

During that period, debates regarding the suitability of conversion initiatives held significant prominence. Following instances of ill-considered abandonments and conversions of churches, the urgency was apparent. This led to the emergence of the Redundant Churches Fund through the Pastoral Measure of 1968 and the Redundant Churches and Other Religious Buildings Bill of 1969. Eventually evolving into the current Churches Conservation Trust, the Fund's inception was driven by the mission “to hold and preserve for the Church and the nation the redundant churches committed to its care61”. The guidelines pertaining to redundant churches originated from pastoral reorganization endeavors and aimed to address the issue of redundancy arising from the shift of residential communities away from urban centres. The matter of church redundancy represented a pivotal moment in the trajectory of conservation policies, leading to a permanent shift in how both dilapidated churches and their upkeep were perceived and managed.

In post-war Britain, the reconstruction of ruined churches swiftly evolved into a chance to modernize the liturgical area, tailoring its dimensions to the community’s contemporary requirements and recalibrating the emphasis on liturgical focal points. Most notably, when circumstances allowed, the process of reconstruction facilitated the reimagining of the church’s space as a cohesive whole, enhancing the feeling of belonging within a unified congregation of worshippers.

Erecting fresh religious structures on the sites of obliterated churches, preserving the vestiges of ruined churches, repurposing discarded materials in new constructions, or converting religious buildings, may seem to contradict the rational principles of technological efficiency and, at time, economics. Nevertheless, the abundance of historical instances and their prevalence in a country like England, frequently linked with a pragmatic and cost-effective approach to urban growth, highlight the involvement of another essential dimension in architecture: memory62.

In the context of ruined churches, the concept of memory takes on a dual significance. The first aspect is associated with location. As historic church structures endure through time, they seamlessly meld with the landscape and are regarded as an inherent part of it, embodying the essence of a place. Thus, the ruined church encapsulates a memory intricately tied to the genius loci. Conversely, and in line with the romanticized notion of ruins, the ruined church incarnates a concept that surpasses its physical location, pertaining to the spiritual identity of a community, denomination, or even a nation. This dual facet of memory finds its roots in Greek mythology, where Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, emerged from the union of Gaia, the earth, and Uranus, the sky. This allegory represents the fusion of these two realms: the terrestrial and the transcendent63.

Special thanks are owed to Claudia Conforti, Maria Grazia D’Amelio, Manolo Guerci and Sofia Nannini. The title is a quotation from Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 1934. The Rock. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. P. 10: “Where the bricks are fallen. We will build with new stone. Where the beams are rotten. We will build with new timbers”. The lines are a quotation of Isaiah 9:10 “The bricks have fallen down, but we will rebuild with dressed stone; the fig trees have been felled, but we will replace them with cedars”.

notes

Several publications have been produced on the subject, including: Diefendorf, Jeffrey M., ed. 1990. Rebuilding Europe’s Bombed Cities. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; Magger, Tino, ed. 2015. Architecture RePerformed: The Politics of Reconstruction. Farnham/Burlington: Ashgate; Allais, Lucia. 2018. Designs of Destruction: The Making of monuments in the Twentieth Century. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

On the aesthetics of Ruins, see: Ginsberg, Robert. 2004. The Aesthetics of Ruins. Amsterdam/New York: Rodopi. In particular chapter 9 Building with Ruin, 185-200; Stewart, Susan. 2020. The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. Chicago/London: The University of Chicago Press.

Ruskin, John. 1849. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. London: Smith, Elder & Co., 233.

They included writers such as Virginia Woolf, John Betjeman, Evelyn Waugh, Elizabeth Bowen and painters such as John Piper, Eric Ravilious and Graham Vivian Sutherland. See: Harris, Alexandra. 2010. Romantic Moderns: English Writers, Artists and the Imagination from Virginia Woolf to John Piper. London: Thames and Hudson.

Eliot, Thomas Stearns. 1934. The Rock. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 20.

See, for instance: Bullock, Nicholas. 2002. Building the post-war world: modern architecture and reconstruction in Britain. London: Routledge; Flinn, Catherine. 2019. Rebuilding Britain’s blitzed cities: hopeful dreams, stark realities. London: Bloomsbury Academic; Saumarez Smith, Otto. 2019. Boom Cities: Architect-Planners and the Politics of Radical Urban Renewal in 1960s Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press. For an overview on reconstruction politics: Rogers, David. 2016. Rebuilding Britain: the aftermath of the Second World War. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited.

Rebuilding Britain. 1943. London: Lund Humphries.

Clapson, Mark, and Larkham, Peter J., eds. 2013. The Blitz and its Legacy: Wartime Destruction to Post-War Reconstruction. Farnham: Ashgate.

Richards, James Maude, ed. 1942. The Bombed Buildings of Britain, a Record of Architectural Casualties, 1940-41. Cheam: Architectural Press.

Ivi, 2.

The transition from rubble to ruins is a key concept. On this theme, applied to the ruins of demolitions, see also: Conforti, Claudia. 2017. “Dalle macerie alle rovine: la misura etica del restauro.” In Gli edifici di via della Conciliazione: Propilei, San Paolo, Pio XII, Convertendi: Ricerche e indagini per il restauro, edited by Maria Mari, 141-145. Città del Vaticano: Libreria Editrice Vaticana.

Macaulay, Rose. 1953. Pleasure of Ruins. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 454.

Nikolaus Pevsner, Reflections on ruins. Talk from ‘In the Margin’, BBC Home Service, May 3, 1946, h. 6.20-6.30 pm. From Games, Stephen. 2016. Pevsner: The BBC Years. Listening to the Visual Arts. London: Routledge, 47-48.

Goodhart-Rendel, Harry Stuart. 1941. “Rebuild or Restore.” The Listener XXV, no. 629 (January 30): 145.

Ivi, 146: “We must not let our ideals continue the dreadful work of the enemy”.

Ivi, 144.

Powers, Alan. 1987. H. S. Goodhart-Rendel: 1887–1959. London: Architectural Association, 25, 42-45.

The church was one of those re-erected by Christopher Wren after the 1666 fire of London.

Burrough, Thomas Hedley Bruce. 1962. “Space and Substance: Two important considerations when radical re-ordering is possible.” In Making the Building Serve the Liturgy: Studies in the Re-ordering of Churches, edited by Gilbert Cope, 57-60. London: Mowbray.

The focus on the altar corresponds to the central position that the Eucharistic rite assumes in the Anglican liturgy of the 20th century. See also: Grieco, Lorenzo. 2020. “‘Ancient Churches and Modern Needs.’ Reordering Anglican Churches in Postwar Britain.” In Architectural Actions on the Religious Heritage after Vatican II, edited by Esteban Fernández-Cobián, 195-210. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

The design of the 19th-century church was by Charles Robert Cockerell.

Burrough, Thomas Hedley Bruce. 1962. Op. cit., 58. Burroughs' restoration of St Andrew's Church has been modified by a recent (2018) adaptation of the building, which has divided the double floor plan into two narrow spaces, reducing the space for the service to a long nave.

On the churches destroyed during the Bristol Blitz, see: Crossley Evan, Martin John. 2000. “The Church of England and the City of Bristol: change, retreat and decay - reform, revival and renewal?.” In Post-war Bristol 1945-1965: Twenty years that changed the city, edited by Peter Harris, Norma Knight, Joseph Bettey, 49-92. Bristol: Bristol Branch of the Historical Association, 58-59.

On the church: J.C.N. S.d. All Saints’ Clifton. [S.l.]: [s.n.]; Cobb, P.G. 1992?. The Rebuilding of All Saints’ Clifton. [S.l.]: [s.n.].

In 1972, the chapel was rearranged to provide an area for smaller worshipping groups, and, at that time, the altar was moved to the centre, bordered by movable communion rails.

This concept resonates with Francesco Borromini's idea of arranging an exhibition of the exposed masonry from the ancient Constantinian basilica within the oculi of the main nave at St. John Lateran. On the oculi, later filled with 18th-century paintings, see: Fagiolo, Marcello. 2013. “Borromini in Laterano: il Nuovo Tempio e la Città Celeste per il Giubileo.” In Roma Barocca: i protagonisti, gli spazi urbani, i grandi temi, edited by Marcello Fagiolo, 265-293. Roma: De Luca, 265-266.

Le Corbusier. 1957. The Chapel at Ronchamp. [S.l.]: [s.n.], 90, 107.

Pehnt, Wolfgang, and Hilde Strohl. 2000. Rudolf Schwarz: 1897-1961. Milan: Electa, 144-155.

Symondson, Anthony. 2011. Stephen Dykes Bower. London: RIBA Publishing.

Ibid.

On St. Mary Bishophill Senior: Royal Commission on Historical Monuments. 1972. An Inventory of the Historical Monuments in City of York, Volume 3, South west. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 30-36.

On the Chapel: Kraus, Stefan. 1997. “Madonna in den Trümmern – Das Kolumbagelände nach 1945.” In Kolumba. Ein Architekturwettbewerb in Köln 1997, edited by Joachim M. Plotzek, Horst Antes, Erzbischöfliches Diözesanmuseum, 51-62. Köln: Buchhandlung Walther König; Kraus, Stefan, Anna Pawlik, and Martin Struck, 2020. Kolumba Kapelle. Monographic issue of Reihe Kolumba, Bd. 59.

The relationship between the chapel and the exterior has been changed by Peter Zumthor's design, which, while keeping Böhm's intervention intact by encapsulating it in level zero of the Kolumba Museum, has transformed the contemplative-ritual power of the ruins into an archaeological stratification. The garden is no longer a place marked by the transience of matter but has taken on the form of a crystallised ruin, with an approach comparable to that adopted more than a century earlier (1806) by Raffaele Stern in the restoration of the southern spur of the Colosseum.

See the recording of the event: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=974zj_BkbY4, accessed December 11, 2023.

Campbell, Louise. 1992. “Towards a New Cathedral: The Competition for Coventry Cathedral 1950-51.” Architectural History, no. 35: 208-234.

Ibid.

Hammond, Peter. 1961. Liturgy and Architecture. New York: Columbia University Press, 135-136.

Kite, Stephen, and Sarah Menin. 2005. “Towards a new cathedral: mechanolatry and metaphysics in the milieu of Colin St John Wilson”. Architectural Research Quarterly 9, no. 1: 85-88.

Thomas, Percy, Edward Maufe, and Howard Robertson. 1951. “Coventry Cathedral Competition.” The Architects’ Journal 115, no. 2947 (August 23): 249-262.

James-Chakraborty, Kathleen. 2018. Modernism as Memory: Building Identity in the Federal Republic of Germany. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 67-72.

Spence, Basil. 1962. Phoenix at Coventry: The Building of a Cathedral. London: Geoffrey Bles, 5-6.

Ivi, 6. The same juxtaposition becomes an iconographic motif in the tapestry that serves as a perspective fugue for the nave of the new cathedral. Made to a design by Graham Sutherland, it contrasts the convulsive figure of the crucified Christ with the hieraticism of a majestic Christ in Glory.

Davies, John Gordon. 1968. The Secular Use of Church Buildings. New York: Seabury Press.

From the plaque affixed to the walls of the church.

Pace, Peter Gaze. 1990. The Architecture of George Pace. London: Batsford, 138-139.

The insertion is explicable of a mechanism of inhabiting old ruins which looks back to history, for instance Bramante’s provisional Tegurio (1513) in St. Peter’s church in Vatican, the church planned by Carlo Fontana (1638) within the Flavian Amphitheatre in Rome, or to the mosque (1715ca) inside the Parthenon in Athens

Augé, Marc. 2004. Rovine e macerie: Il senso del tempo. Torino: Bollati Boringhieri, 43. Trans. by the author.

Moshenska, Gabriel. 2010. “Charred churches or iron harvests?: Counter-monumentality and the commemoration of the London Blitz.” Journal of Social Archaeology, 10 (1): 5-27.

The Editor. 1944. “Save Us Our Ruins [with a Foreword by the Dean of St. Pauls, W.R. Matthews].” The Architectural Review, 95, no. 565 (January): 13-14.

Allen of Hurtwood, Marjory, David Cecil, Kenneth Clark, F. A. Cockin, T. S. Eliot, H. S. Goodhart-Rendel, Julian Huxley, Keynes, E. J. Salisbury. 1944. “Ruined City Churches. Letter to the Editor of the Times.” The Times, August 15.

Ibid.

Matthews, Walter R. 1945. Foreword to Bombed Churches as War Memorial.

On the volume, see: Larkham, Peter J., and Joseph L. Nasr. 2012. “Decision-making under duress: the treatment of churches in the City of London during and after World War II.” Urban History, 39, 2 (May): 285-309; Larkham, Peter J. 2019. Bombed Churches, “War Memorials, and the Changing English Urban Landscape.” Change Over Time, 9/1 (Spring): 48-71; Clark, Benjamin. 2019. “Curating Catastrophe: The Enduring Legacy of Bombed Churches as War Memorials.” Accessed February 2023. www.donaldinsallassociates.co.uk/curating-catastrophe-the-enduring-legacy-of-bombed-churches-as-war-memorials.

Bradley, Simon, and Nikolaus Pevsner. 1998. London: The City Churches. London: Penguin, 53-54. The crumbling structure of the bell tower was dismantled and reassembled with modern technology in 1960; two years later, the eastern walls were demolished to widen the adjacent road; in 1989, a public garden was created within the remaining walls; and finally, in 2006, the tower was converted into a private residence.

Hauer Christian E. Jr., and William A. Young. 1994. A Comprehensive History of the London Church and Parish of St. Mary, the Virgin. Aldermanbury: The Phoenix of Aldermanbury.

They were all very active in campaigning. Goodhart-Rendel was also a member of the Incorporated Church Building Society, as John Betjeman was a founding member of the Victorian Society.

friendsoffriendlesschurches.org.uk/about-us/. Accessed August 2023.

Temple, P., ed. 2008. Survey of London. Vol. 47. London: Yale University Press, 192-216.

api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1968/may/09/pastoral-measure; api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1969/feb/19/redundant-churches-and-other-religious.

On Memory in architecture see Treib, Marc. 2009. “Remembering Ruins, Ruins Remembering”. In Spatial Recall: Memory in Architecture and Landscape, edited by Marc Treib, 194-217. New York/Oxon: Routledge.

Hesiod, Theogony, 135.

Edited by: Annalucia D'Erchia (Università degli Studi di Bari), Lorenzo Mingardi (Università degli Studi di Firenze), Michela Pilotti (Politecnico di Milano) and Claudia Tinazzi (Politecnico di Milano)

Lisa Henicz

Tom Avermaete Leonardo Zuccaro Marchi

Luigiemanuele Amabile Alberto Calderoni