The long and successful career of Ada Louise Huxtable (New York, 1921-2013) is one of many firsts: first woman to win a Fulbright Fellowship in Architecture in 1950, first appointed full-time critic of architecture for an American newspaper – the New York Times – in 1963, first Pulitzer Prize winner for Distinguished Criticism in 1970.

Since the post-war period, her voice has always been the most recognizable in American architectural journalism and criticism, two fields that she contributed to establish and evolve. Her splendidly written, acute, and often caustic observations on the many changes occurring in the American-built world were, at the same time, the most awaited by her affectionate readers, as well as the most feared by architectural firms, politicians, and building contractors.

In the ever-changing built context of the United States from the Fifties onwards, Huxtable has started and shared many subjects of discussion and reflection arising from the vivid observation of the reality around her. Saluting with sharpness the many achievements in the fields of architecture and planning, she witnessed with her incisive pen the rise and evolution of different new sensitivities in design. Her writings didn’t spare to direct many ferocious attacks against the demolition of landmarks and their replacement with “shoddy or undistinguished” new projects or, even worse, with “reproductions… preferred to originals”. She vehemently warned the public opinion about the approval of urban plans that she reputed a danger against the quality and character of the built environment, “a good way to kill off a city, as well” [p. 49].

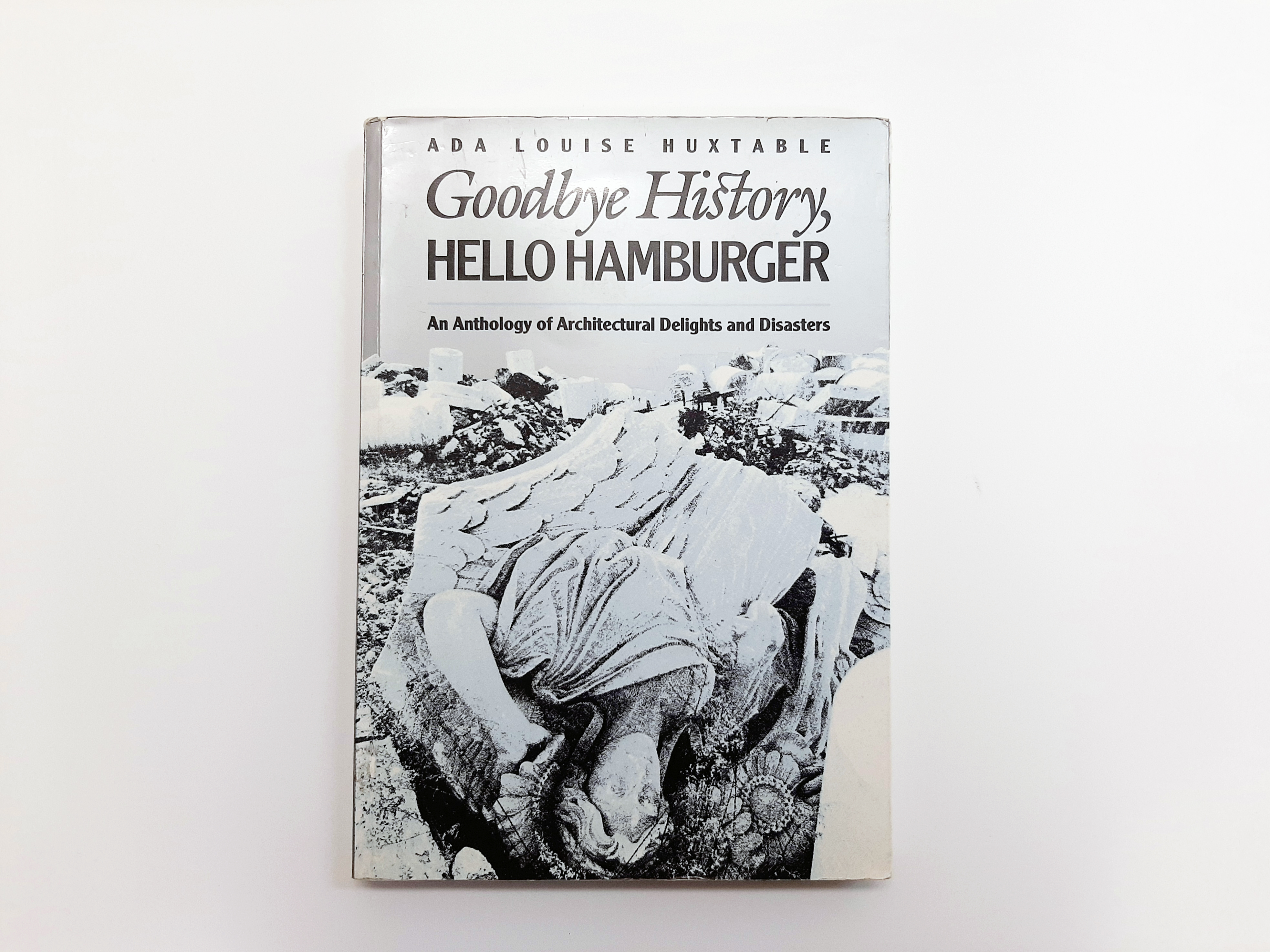

Her most famous pieces devoted to the causes of preservation and restoration, in all of its multifaceted and eclectic definitions, are collected in the 1986 book Goodbye History, Hello Hamburger. As anticipated in the exquisite subtitle, the Anthology of Architectural Delights and Disasters collects 63 articles documenting Huxtable’s view on the topics of urban and architectural preservation, mostly published in the pages of the New York Times during the Sixties and the Seventies. Her major object of research is New York and the urban development occurring in its boroughs, and especially in Manhattan. But Huxtable’s pieces address the many changes in the American city in general, among them the “side street sabotage” in Syracuse, controversial restoration projects in Baltimore, and the loss of Mapleside historic house for a Burger King in Madison, Wisconsin, a story that is also recalled in the title of the book.

The articles are ordered in seven thematic sections, named in no less evocative way then the title of the book itself: How to Kill a City, Preservation or Perversion?, The Fall and Rise of Public Buildings, Urban Scenes and Schemes, Old Friends and Delights, The Near Past, Where the Past Meets the Future.

In all of these sections, Huxtable wrote about the deliberate destruction of the historic urban fabric as well as the intentional demolition, alteration, replacement or counterfeit of significant buildings considered by the critic as an essential matter of the public good, major factors in “the city’s future quality and identity” [p. 11].

In the second section, Preservation or Perversion?, are present the articles which recount the story of the most passionate and lost battle of Ada Louise Huxtable in this field: her fight at the forefront to save the original Pennsylvania Station in New York, completed by McKim, Mead and White in 1910 and demolished, among harsh criticism, public protests and much dismay, in 1963. In her column, The Impoverished Society (May 5, 1963), Huxtable announces that: “The final defeat for Pennsylvania Station was handed down by the City Planning Commission in January, and the crash of 90-foot columns will be heard this summer”. The piece continues describing the tragic fate of Penn Station as a “civic loss” that impoverishes the whole society: “We can never again afford a nine-acre structure of superbly detailed solid travertine […]. It is a monument to the lost art of magnificent construction, other values aside. The tragedy is that our own times not only could not produce such a building but cannot even maintain it” [pp. 47-49].

The subsequent article, A Vision of Rome Dies, adopts a bitter obituary literary style: “Pennsylvania Station succumbed to progress at age 56 […]. The passing of Penn Station was more than the end of a landmark. It made the priority of real estate values over preservation conclusively clear” [p. 49]. This is a point steadily supported by Huxtable, that on various occasions pointed out the responsibility of the real estate market for the disappearing of “the texture, quality and continuity of the city” [p. 14]. Calling New York “the Mortal Metropolis” in opposition to the “Eternal City”, Huxtable analyzes the “Roman splendour” of Penn Station from an economic, functional, as well as aesthetic and historic points of view, with precise references to classical architecture that reveal her deep knowledge of Italian culture gained first-hand during her scholarships to Italy [pp. 49-51].

Her writings made Huxtable a competent and appreciated voice among American scholars and professionals in the fields of preservation and urban planning, among them Giorgio Cavalieri, Jane Jacobs, and Lewis Mumford, as well as among associations and organizations which asked for her collaborations, such as the National Trust for Historic Preservation, that is also the publisher of this book. Protagonist on the cover of Goodbye History, Hello Hamburger is the sculpted marble angel of Pennsylvania Station thrown to the ground, reduced to pieces, and surrounded by rubble. No doubt, Penn Station remains Huxtable’s first and fieriest campaign against the degradation not only of landmarks but also of the sense of the city. The final lines of Farewell to Penn Station, a short comment published in the New York Times on October 30, 1963, reveals Huxtable’s position on the problematic legacy to pass to future generations: “We will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed”. And yet, this sounds not as a nostalgic weeping over the past, but as a firm call to take action for the protection of the future.

Goodbye History, Hello Hamburger. An Anthology of Architectural Delights and Disasters

Ada Louise Huxtable

The Preservation Press, National Trust for Historic Preservation

Washington, D.C.

1986

178x254 mm

206 pages

English

0891331190

Pages from "Goodbye History, Hello Hamburger. An Anthology of Architectural Delights and Disasters" by Ada Louise Huxtable (1986)